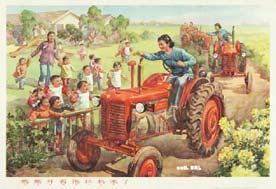

In China, under the regime of Mao Tse-Tung, conventional forms of femininity were considered bourgeois, according to UO sociologist Eileen Otis. "Sex neutrality" was the rule in the factory and the field.

But things are different in China's 21st century economy, according to Otis. With economic reforms, services have mushroomed in China's cities and women are being channeled into low-wage service jobs at an unprecedented rate.

Now, "being young, attractive and sexy is a service-career maker for young women -- who are often fired as they approach their late 20s, considered too old and unattractive," Otis observed.

Otis has studied young female service providers in China's big city hotels. She notes that previous generations, under Mao, were raised with the Communist ideal of "guaranteed work." They labored in gender neutral workplaces where market competition didn't exist. Their daughters, on the other hand, are entering into markets defined by capitalist competition. Their employers, in order to succeed, are adapting to Westernized styles of service, which include hiring young, nubile women.

To understand the way service work has been evolving, Otis studied two hotels, one devoted to high-class international clients in Beijing, and the other in the smaller, less wealthy province of Kunming. She noted that both hotels expected women to wear make-up, address clients personally, and to smile, walk and talk like Americans. But in both locations, imported western femininity had been adapted to local context.

In Beijing, Otis watched male supervisors pantomime Western femininity -- showing their staff the right way to speak, and to look directly into the eyes of male customers and smile. The girls were encouraged to use such tactics to give a customer status or "face," to show respect.

Direct eye contact might seem to imply intimacy or even risqué behavior for young Chinese women. But because they see it as "giving face," said Otis, this allows them to maintain a psychological distance. The workers do not see themselves as providing intimate or authentic service (which is the attitude of workers in the U.S.).

In Kunming, said Otis, where prostitution was common within the hotels themselves, the women still mimicked a western ideal, but a modified version. They emphasized their personal virtue, using a professional bearing to deflect unwanted attention, wearing light make-up and smiling rarely so as not to appear too available.

When asked by a customer to join him at a karaoke bar, a 21st-century worker in Beijing might smile coyly and ask, "Can I bring my boyfriend?" In Kunming, she might point sternly at her name badge, reminding the customer of her function, and then continue to recite a list of delectable food and drink items available at the restaurant.

Back in the days under Mao, young female workers might have rebuffed an ardent customer bluntly. But under the new rules, the customer must never be directly confronted.

- Chrisanne Beckner

All images from the collection of Stefan Landsberger

Watch Darwin talks, read an essay by the "Weird Science" professor.

Watch Darwin talks, read an essay by the "Weird Science" professor.