When the IED detonated, Byron Etta’s vehicle lifted off the ground. He remembers a giant red flash and the force of being thrown upward, hitting his helmeted head on the ceiling of the rig and then landing right back in his seat. The improvised explosive device blew the engine off, and the driver and gunner sustained concussions; everyone scurried outside to take up defensive positions. In the distance, Etta heard guns going off as Iraqi insurgents celebrated a successful attack on the enemy.

Byron Etta (left) and a communications specialist from his unit, in a convoy vehicle in Balad, Iraq. Riding in one of these mine-resistant, armor-protected vehicles made him feel “like a starship trooper.”

Etta, at the time a twenty-two-year-old medic on his second tour in Iraq, was changed instantly: “I knew I had been closer to dying than I ever had in my life,” he said. “That visceral fear, visceral pain, visceral anguish was unparalleled. The importance of life felt unsurpassed to me. Once I felt it, I couldn’t hurt another person.”

It was a terrifying experience—and just what a young doctor-to-be needed.

Now finishing his degree in biology at the UO, Etta had spent his freshman year at the University of Chicago as a premed student without enough focus; it had pretty much been a bust. Between the academic demands and a part-time job, he was quickly overwhelmed, with slipping grades and mounting debt. So he quit school and joined the Army to be a medic, seeking not just the financial support to further his education but a trial-by-fire experience that might tell him whether he truly had the commitment for a career in medicine.

Etta served two tours in Iraq, 2006–7 and 2008–9. He drained fluid from a patient’s lungs by inserting a chest tube and he treated Iraqi nationals with third-degree burns over 95 percent of their bodies—all in the middle of a combat setting. Etta described an incident in which a soldier had been hit with shrapnel; he coolly applied a tourniquet and an intravenous morphine drip while the patient, in agony, screamed at him.

Right: Etta (on the floor), instructing Iraqi nurses on cervical spine immobilization. Iraqi doctors helped Etta bridge the language gap.

“I really hoped I was the type of person who wouldn’t freak out under pressure,” Etta said, “but you can’t possibly know until you have been in that situation.”

Finding the violence of war intolerable, Etta eventually applied for and received “conscientious objector” status. While waiting for the paperwork to go through, he created and taught a combat trauma course for Iraqi doctors and nurses, ending his service with an honorable discharge.

At the UO, Etta no longer needs a part-time job because his studies are covered between the GI bill and his receipt of a Tillman Military Scholarship. Named for the former NFL player Patrick Tillman, who quit his professional football career for military service and was killed in Afghanistan in 2004, the scholarship supports active and veteran service members and spouses by covering tuition, fees, housing and child care.

Etta is studying the genetic basis for behavior in the model worm organism, Caenorhabditis elegans. He’s helping to zero in on the gene that is responsible for development of a neuron used to sense and respond to temperature; the work will help bridge the gaps between genes, neuron differentiation and behavior.

Having survived the crucible of war, Etta now finds it much easier to tackle an academic challenge like organic chemistry. His grades are high and his sights are set on graduation this June and beginning his first year as a medical student at Oregon Health & Science University next fall. In those medical school interviews, he had a lot to say when asked time-honored questions about “personal growth” or “dealing with adversity.”

“I’ll never be colder, never be hotter, never more uncomfortable or more in danger than I was in Iraq,” Etta said. “Having that experience to provide my motivation is the difference between me before military service and now.”

-Matt Cooper

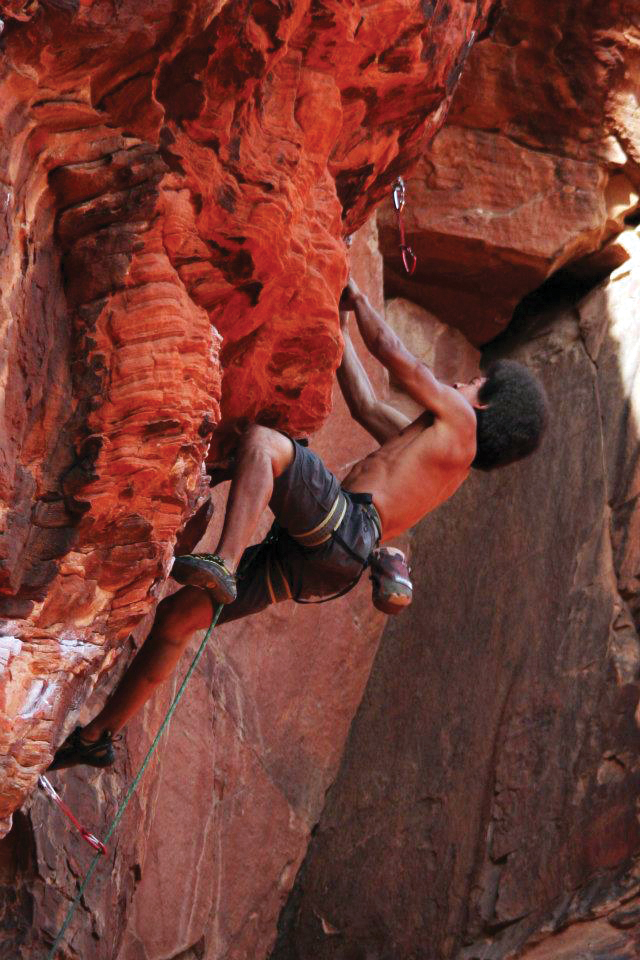

When he’s not studying the genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans, Etta (left) indulges his passion for rock climbing.

"You are your microbes," is the message from UO biologists in a TED Ed video and TEDx talk.

"You are your microbes," is the message from UO biologists in a TED Ed video and TEDx talk.