by Marc Dadigan

Centuries ago, explorer Balboa Vásquez de Nuñez declared the Pacific Ocean and all the lands it touched as the possession of Spain. Fast forward to the 18th century, when Juan Pérez began to explore the Northwest coast. These two Spaniards had a significant jump on Lewis and Clark, who made their much-heralded journey to Oregon at the beginning of the 19th century.

“The history of pioneer Oregon often focuses on the Anglo settlement, the old wagon and Oregon Trail narrative,” said Lynn Stephen, professor of anthropology and ethnic studies. “When you add these earlier stories, it really enriches the complexity of our history.”

“The history of pioneer Oregon often focuses on the Anglo settlement, the old wagon and Oregon Trail narrative,” said Lynn Stephen, professor of anthropology and ethnic studies. “When you add these earlier stories, it really enriches the complexity of our history.”

Stephen, along with collaborator and documentary filmmaker Gabriela Martínez, have become explorers themselves, delving into the history of Latinos in Oregon, and especially Lane County. Their work is gaining prominence just as Oregon’s reputation as a homogenous state is increasingly becoming a thing of the past.

In 2006, Latinos made up more than 10 percent of the population in Oregon, and the population of Latino students in public schools has grown by 200 percent in the past 10 years. Projections estimate that by 2020 nearly 30 percent of high school enrollment will be Hispanic or Latino.

Yet Stephen points out that all the talk of “changing demographics” is a little timebound.

“If you want to talk about Latino influence, you have to go back hundreds of years,” she said. “Before Oregon was a state, California was part of Mexico and while the Mexican border was fluid, it came up to around Medford.” In other words, Oregon was a border state.

To raise public awareness of Oregon’s historic links with Latin America and the long-term Hispanic presence in the state, Stephen has been the driving force behind the Latino Roots project. This began as an ethnographic exhibit at the Lane County Museum in 2009 and this fall will expand into two undergraduate classes that will give students direct experience in documenting Oregon’s Latino past. The classes are supported by grants from the Office of Institutional Equity and Diversity, the College of Arts and Sciences and the Williams Council.

To raise public awareness of Oregon’s historic links with Latin America and the long-term Hispanic presence in the state, Stephen has been the driving force behind the Latino Roots project. This began as an ethnographic exhibit at the Lane County Museum in 2009 and this fall will expand into two undergraduate classes that will give students direct experience in documenting Oregon’s Latino past. The classes are supported by grants from the Office of Institutional Equity and Diversity, the College of Arts and Sciences and the Williams Council.

In collaboration with Martínez, an assistant professor in the School of Journalism and Communication, Stephen will teach students about the history of Oregon’s Latinos and then train them to conduct oral history interviews, with the aim of creating student-produced documentaries as a capstone project. A dedicated website will serve as a continually updated public archive of the materials produced by students.

Beyond the Farmworker Stereotype

The students’ work will add to the existing collection of stories, photographs and artifacts that the Latino Roots team originally organized for the Lane County Museum exhibit.

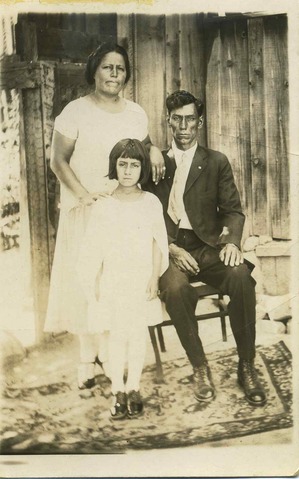

For the original exhibit, graduate students assisted Stephen and Martínez as they reached out to local Latino community leaders to find appropriate subjects for oral history and video interviews, while also collecting historical information and photographs. Artifacts showcased in the exhibit included a bilingual Bracero contract that had belonged to one subject’s father as well as corn grindstones, called metates, used to make homemade tortillas.

For the original exhibit, graduate students assisted Stephen and Martínez as they reached out to local Latino community leaders to find appropriate subjects for oral history and video interviews, while also collecting historical information and photographs. Artifacts showcased in the exhibit included a bilingual Bracero contract that had belonged to one subject’s father as well as corn grindstones, called metates, used to make homemade tortillas.

“We looked for people who came from different times and different parts of Latin America or the U.S.,” Stephen said. “We were particularly interested in showing their contributions and to get away from the stereotype that everyone is a farm hand, cook or gardener.”

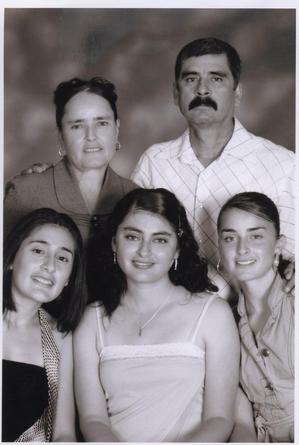

Stephen and Martínez conducted a total of nine interviews, including oral histories of a Chilean couple who earned advanced degrees, a blue-collar Mexican immigrant couple whose three children attended the UO and the owner of Plaza Latina, the local Latin American grocery store.

Martínez, who produced the video interviews for the exhibit, said she realized in producing these documentaries how much she had bought into the Latinos-as-farmworkers stereotype—despite the fact that she is a native of Peru—and was impressed by how many participants were highly educated.

Yet she was touched by the conflicting depictions of Lane County conveyed by the interview subjects—as a place that at times was hostile to their presence but at others provided a unique and vibrant place to raise their families.

Telling this more complete history of Oregon, Stephen said, can only benefit the local community.

“It’s great for Latinos and for everybody to know the richness of the state’s history,” she said. “Understanding the deep history and hearing from today’s Latino professionals can disrupt some of the polarizing narratives that keep us from valuing multiculturalism like we should.”

* * *

The Latino Roots exhibit at the Lane County Historical Museum, on display in 2009 in celebration of Oregon’s 150th birthday, also celebrated the underrepresented history of Latinos in Lane County. The artifacts curated for the exhibit documented the family, social and occupational lives of Latinos who have populated the county for generations. A filmed documentary, as well as written materials, gave voice to individuals who shared their personal stories of both hardship and joy, as they worked toward establishing their lives in Lane County.

The stories below of Roberto Arroyo, Selene Jaramillo and Patricia Cortez were all originally part of the Latino Roots exhibit.

Lives Forever Changed By The Junta

Selene Jaramillo and Roberto Arroyo were born in different cities in the south of Chile, where it rains as much or more than in Oregon. Selene was born in 1968, in Valdivia, a city where the Wuilliche, German and Chilean cultures coexist. Roberto was born in 1959 in Temuco, a city marked by having the largest presence in Chile of the Mapuche culture and people. Today there are also Chileans and descendants of European colonizers living there. Both Selene and Roberto have lived in a permanent diaspora, each for their own reasons.

Selene lived through the experience of the military coup of September 11, 1973, when she was only five years old. In 1976, she and her brother left on a voyage with their mother Nancy, a Spanish teacher, and their father Alfonso, the captain of a fishing boat. They sailed for 23 days to reach Mexico, where they sought asylum from the violence that took over their country. Because of this, for more than 15 years Selene and her family were listed by the Chilean government as people forbidden from entering Chile. At the age of seven, she was officially labeled a terrorist.

From 1976 to 1982, the family lived in different places in Mexico, including Acapulco, Mexico City, Guanajuato and Mexicali. While in Mexico, their boat was lost, and so was the family after a divorce. Selene and her brother ended up living with their father and in 1982 they came to the U.S. They arrived in Chula Vista, California, where Selene attended high school and started to work with her father selling pottery. Concurrently, she worked at Sea World, taking Polaroids of children posing with a guy wearing a whale costume.

In 1991, Selene transferred to the University of California at Berkeley. In 1992 she spent a year abroad living in Sao Paulo, Brazil. In 1994, she returned to UC Berkeley to pursue a master’s degree and worked for a recycling program in the city of Oakland. She lived in Berkeley until 1998. Today Selene and her brother are U.S. citizens. Their father died a few years ago and their mother returned to Valdivia.

Roberto’s family also was very affected by the dictatorship in Chile (1973–1990). Many of his relatives suffered the consequences of this brutal period.

His uncle Anselmo Raguileo, an important Mapuche leader, was savagely tortured in the main concentration camp at the National Stadium of Chile, and many other relatives and friends suffered torture, were exiled or came to the uncertain end of becoming “disappeared” at the hands of the police or the military. A cousin was detained, tortured and disappeared in Argentina. His father lost his job because he refused to collaborate with the dictatorship.

In junior high school, Roberto attended an industrial-technical school for the children of workers, Mapuches and other kids who were also, like Roberto, the children of public employees.

In 1977, Roberto started to work for a resistance organization. He was 17 years old and this coincided with his first year in college, where he studied music pedagogy. These were the clandestine years. Roberto learned to forget his name and to forget the faces of his friends. Showing affection to friends was a careless action that could lead to death.

During these times, to produce art or poetry, or to sing songs, became subversive acts and Roberto joined different cultural movements and bands. As a musician, he was a member of “Schwenke y Nilo,” a group in Chile’s New Song movement.

As an artist, he held numerous individual and collective expositions and conferences about his art in Chile, Ecuador, England, Croatia, Germany and the United States. He developed an extensive body of work on the subject of human rights, most recently under the title “Amor Contra el Olvido (Love Against Forgetting).”

Roberto has spent most of his life since the age of 13 working as a human rights activist and investigator. This has included the search for hundreds of disappeared detainees. He has participated as a consultant in a forensic anthropology team in five exhumations of the remains of people who were massacred during the military dictatorship.

Selene and Roberto met in Chile in 1997, when she was visiting her family. Roberto left Chile and came to the United States following his heart. They first lived in Salinas, California, where Selene worked—first in an organic agriculture program and then in a health research project—with small-farmer immigrants who came from diverse places in Mexico.

In 2003, Selene and Roberto moved to Eugene so that Roberto could start a PhD program at the UO, in Romance languages. Selene found work with Lane County, and works there today in the Public Health Department. Selene and Roberto have children and grandchildren in Chile.

The American Dream

Patricia Cortez was born in El Salvador 45 years ago. Her family was not only extremely poor, but also caught in the political violence between insurgency groups and the government. On Patricia’s father’s side, aunts, uncles and cousins were “disappeared” and never found; one uncle was killed outright for refusing to move from his home.

Archbishop Oscar Romero’s courageous stand to end oppression of the poor inspired Patricia, her older brother and two of her cousins to join his mission in the late 1970s. She and her brother were constantly harassed and in several cases beaten by military groups. Patricia’s two cousins were later kidnapped, tortured and killed. Patricia’s brother is one of a thousand who disappeared during those turbulent times.

More than once Patricia was detained and interrogated for hours because she was a student organizer. She was also subjected to sexual harassment. One officer’s behavior so repulsed her that she spit on him. For that, she was kicked and beaten so badly that she ultimately became sterile.

While attending La Universidad National (National University), Patricia collected signatures to help support students’ rights. One day she was informed by a classmate that the police were looking for her. While in hiding, she learned that the police had gone to her parents’ home and beaten her father. The knowledge that her parents’ lives, as well as her own, were in danger caused Patricia to leave El Salvador. Friends had called the United States “the American dream, the land of opportunities,” leading Patricia to seek political asylum here. She arrived in Pasadena, California, in 1985. Two years later, she moved to the Mission District in San Francisco and lived there for 11 years, working in many minimum-wage jobs.

In 1997, Patricia moved to Eugene and returned to school. She was aware that usually she was the only Latina present, but believes her first impression was naïve. Later, she started to experience discrimination. One time, the occupants of a passing car threw a bowl of blackberries at her, screaming, “Go back to Mexico.”

Patricia enjoys meeting all the hard-working activists of Eugene, and appreciates the collective effort to build community. She has observed an increase in the number of Latinos making their homes in Lane County.

She notes, “It is a mistake to think that all Latinos living in Eugene and Springfield are from Mexico. Immigrants of Latin heritage come from many different countries, including Ecuador, Honduras, Peru, El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, Chile, Argentina, Colombia, Cuba and Puerto Rico.”

Patricia Cortez has persevered. She has lived with her soul mate for 13 years, and in 2004 received her master’s degree in social work from Portland State University. She is dedicating her life to helping Latino youth and their families. Patricia has never been able to return to El Salvador for fear of additional violence against her parents and herself.

Learn how experts across disciplines are together advancing green chemistry.

Learn how experts across disciplines are together advancing green chemistry.