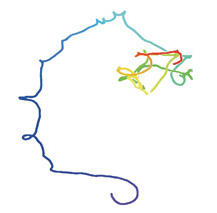

Purple marks the beginning

of one worm's search for food.

When the line turns red, the

worm has arrived at its next meal.

How did this worm chart its path? Through taste, smell and ... calculus.

That's what UO biologist and member of the UO Institute of Neuroscience Shawn Lockery has discovered. Worms calculate how much the strength of different tastes is changing -- equivalent to the process of taking a derivative in calculus -- to figure out if they're heading toward food or should tack in a different direction.

By testing the nematode's response to salt and chili peppers, Lockery, the principal investigator, and his team of five scientists determined that the worm's food-seeking behavior is similar to a game of "you're getting hotter, you're getting colder" with a child. Salt equals hot. Spicy equals cold. Except the worm doesn't need to be told if it's getting closer to or farther from the target -- the worm calculates the change by itself.

The discovery, published this summer in the journal Nature, suggests that this method for smelling and tasting may be common among a wide variety of species, including humans. Better understanding of how taste and smell function in the brain of a nematode, Lockery said, may one day benefit human beings, especially the more than 200,000 Americans whose senses of taste and smell are impaired.