Throughout elementary and high school in Monmouth, Oregon, La Donna Forsgren was the only African American in her class. Her colleague, Michael Najjar, had a similar experience growing up as part of a minority, as a first-generation Arab American.

Even though their respective subjects—African-American theater and Arab-American theater—are wholly different, Forsgren and Najjar are both interested in the stage as a means to explore, comment on and critique issues of race, immigration, discrimination, identity and justice.

“They’re brand new energy,” said John Schmor, head of the theater arts department. Schmor believes their academic expertise, experience as directors and intimate relationship with their subject matter are an ideal mix.

“We want students to graduate with not only performance experience, but also with an understanding of the historical and political phenomena that inspire the theater arts,” he said. “La Donna and Michael deliver both.”

Raised in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Michael Najjar— whose birth name is Malek— recognized early on the incongruence

Raised in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Michael Najjar— whose birth name is Malek— recognized early on the incongruence

between his home life of traditional Lebanese food and folklore and his day-to- day experiences as an American kid. Most challenging were the incidents that arose whenever a crisis broke out in the Middle East.

“By virtue of the fact that we were Arab American, we were automatically associated with any of the conflicts from the Middle East,” he said, even when such conflicts did not involve Lebanon.

For instance, when the U.S. bombed Tripoli in 1986, “I was teased as being Libyan—read: supporter of Qaddafi,” he recalled. “Or when there were outbreaks of Palestinian violence I would be called a Palestinian. What they meant was that I was like those people.”

Like many first-generation Americans, he grew up straddling two cultures.

“We are ‘hyphenated Americans,’” said Najjar. “Many Arab Americans, like other ethnic groups, have dual loyalties: an identity in a homeland and also pride in being an American—with tension arising between the two especially in times of strife.”

And when there’s strife—like, say, in a world complicated by the 9-11 attacks and subsequent wars—the question becomes “do you sublimate your identity, or do you embrace it?” Najjar said. For instance, “there are many Arab Americans who warn, ‘don’t speak Arabic in public.’”

Najjar recognizes this fear of persecution as a pressure universal to immigrant groups throughout history. “Italian Americans suffered in the 1920s, Asian Americans during World War II. Today Arab Americans and Latin Americans are going through it,” he said.

For Najjar, theater is a medium to bring this experience to life, and to redefine Arab culture for American audiences.

The latter objective was a motivating factor behind his decision to direct Dominic Cooke’s Royal Shakespeare Company adaptation of Arabian Nights, as his first UO production last spring.

“Americans have images of Arab nations based on fantastical interpretations of the Middle East,” said Najjar, pointing to Disney’s Aladdin as an example. “In many ways, the tales of Arabian Nights, as they’ve been handed down to us by the French and British, have only perpetuated our view of the people of the Middle East and South Asia as utterly foreign.”

While U.S. children may be familiar with iconic imagery of Arab folktales— flying carpets, camels and sand dunes— Najjar said he wanted his production to focus on the people in Arabian Nights.

“One of my goals was to take these stories, which are beautiful, human stories, and get them back to the source material—to a perspective that is not based in Eurocentric views,” he said.

Arabian Nights follows the traditional story line of One Thousand and One Nights in which literature’s legendary storyteller—the play’s female protagonist, Shahrazad—tells to a murderous king 1,001 consecutive nights of tales to save herself from execution. Among the tales she tells are “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves” and “History of Sinbad the Sailor.”

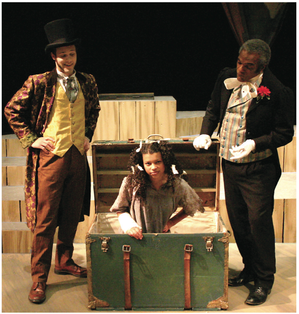

In Najjar’s production (left), audiences were treated to elaborately choreographed Middle Eastern dancing and costumes designed to reflect ancient Persian dress.

“Ultimately it’s a play that speaks to humanity, and to the story of what happens when people lose their way,” Najjar said.

A Healthy Respect for the Absurd

Race may be a serious subject, but serious is not a word you would use to describe La Donna Forsgren.

“I love to laugh and I have a healthy respect for the absurd,” said Forsgren. “Just because something is a tough subject doesn’t mean it can’t make you laugh.”

Forsgren is the first black theater professor to set up shop in Villard Hall, but is undeterred by the relative racial homogeneity of Oregon and the UO campus. “This department is obviously interested and supportive of expanding perspectives on theatrical material,” she said. “The UO is excited about diversity.”

Forsgren said she embraces the opportunity for self-examination and rich contemplation that discussions about race bring to the surface. “People don’t like to talk about race, but it is important that we do,” she said. “Race influences our decisions, interactions and beliefs.”

Forsgren sees theater as a means for overcoming the discomfort the subject of race can create.

“Theater is an opportunity to engage heavy topics in a safe environment, if you can do it in a way that is entertaining,” she said. She calls her philosophy “edutainment”—teaching through entertainment. “I want to get rid of the passive audience. I take these topics and make them playful.”

Among her inspirations are comedians. “I love Dave Chappelle. He’s funny, but he also makes you think critically,” she said. Chappelle shot to stardom for his parodies of American culture, especially racial stereotypes, on his sketch comedy TV series that ran from 2003 to 2005.

Her classes have been packed, with a waiting list of students eager to fill vacancies. “A wide range of students is interested in the subject of race,” said Forsgren. “I have African American students, international students, white students. It makes for lively conversation.”

Last spring Forsgren made her UO directorial debut with Robert Alexander’s, I Ain’t Yo’ Uncle: The New Jack Revisionist Uncle Tom’s Cabin (below), a play in keeping with her philosophy.

The play, a satire, explores America’s racial past by bringing the characters of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s influential novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, to life in the twenty- first century. On stage, modern versions of Uncle Tom, Topsy and Eliza emerge from the streets of the inner city to put Stowe on trial for creating stereotypes about African American identity.

Forsgren said she picked the play because it offered the opportunity to explore the cultural construct of “blackness”—from overtly racist blackface minstrel performance traditions of the past to stereotypes within popular culture today.

The fact that it incorporates 1990s hip-hop, which she loves, was also a selling point. “It’s also just plain funny,” said Forsgren. “For those who have ever wondered what Stowe’s characters would say if they could write their own stories, this show provides the hysterical answers.”

While reviled as a people, the Roma of Eastern Europe are revered for their music.

While reviled as a people, the Roma of Eastern Europe are revered for their music.