Charise Cheney’s project will shed light on the little-known anti-integrationist movement among African Americans in Topeka.

Charise Cheney’s project will shed light on the little-known anti-integrationist movement among African Americans in Topeka.

Cheney was born and raised in Topeka, Kansas, the city that came to symbolize the desegregation movement because of a lawsuit that challenged the school district’s policy of racial segregation, and then went all the way to the Supreme Court.

But Cheney was surprised to learn that African American support for desegregation in 1950s-era Topeka was not nearly as widespread as she had thought.

So surprised, in fact, that she has decided to write a book about the on-the- ground reality in her hometown during the early days of the civil rights movement.

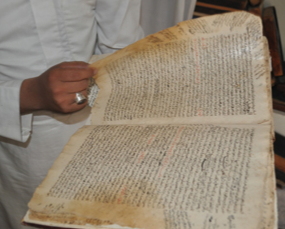

Topeka’s African American teachers in 1949. “Many black Topekans wanted to preserve all-black schools,” says Charise Cheney.

Cheney’s project will shed light on the little-known anti-integrationist movement among African Americans in Topeka prior to the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision, which outlawed racial segregation in public schools across the land.

“Many black Topekans wanted to preserve all-black schools because they were relatively equal to all-white schools and because they fostered a familial and nurturing learning environment for black children,” said Cheney, associate professor of ethnic studies.

Topeka became a poster child for the desegregation movement because of Brown, she said, but the truth is more complicated than any textbook-style overview could reveal. For instance, “Resistance to the NAACP was also very strong in Topeka’s black community at the time,” she said.

Cheney anticipates that the book will be in print in plenty of time for the sixtieth anniversary of the Brown decision in 2014.

Cheney, who joined the UO ethnic studies faculty in 2010, likes to challenge students to question their own political views and to consider both the privileges they enjoy as university students and the social responsibilities attached to those privileges.

In the classroom, she likes to use a comparative approach to examine the evolution of race and racism in the

United States. “I love teaching from an interdisciplinary, multivocal perspective,” she said. “African American history becomes more textured and nuanced when juxtaposed against the histories of indigenous peoples, Latinos and Asian Americans.”

Cheney has taught a number of ethnic studies courses at the UO, including Critical Race Theory and Hip-Hop Poetics and Politics. Another course—Critical Whiteness Studies—examines the social construction of race by delving into the history of “whiteness” as a racial category in the United States. Next spring, she is teaching a course titled Modern Civil Rights Movement, which looks at how scholars have framed the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s and examines trends in historical writings.

“Scholarship challenges us to rethink how we see the civil rights movement as a historical moment,” she said.

Cheney is also the author of Brothers Gonna Work It Out: Sexual Politics in the Golden Age of Rap Nationalism (New York University Press, 2005), an exploration of black nationalism and hip-hop culture.

—Eric Tucker

Photo courtesy Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site

Watch

Watch  Watch excerpts from the opera, coming soon to Eugene.

Watch excerpts from the opera, coming soon to Eugene.

Three’s a charm for a living memorial.

Three’s a charm for a living memorial.