Linguistics professor Tyler Kendall challenges the myth of the “broadcast standard” dialect in the Western half of the U.S.

A common perception about language is that we are losing regional dialects—those variations of dropped Rs or twangy vowels that distinguish populations as being distinctly “Boston” or “Wisconsin” or “South Texas.”

After all, with increased mobility, national television and the Internet, our exposure to each other and to mass culture in general has been increasing for decades. Surely, we are all moving toward a norm where everyone sounds essentially like Brian Williams of NBC Nightly News.

But Tyler Kendall, an assistant professor of linguistics at the UO, challenges this assumption.

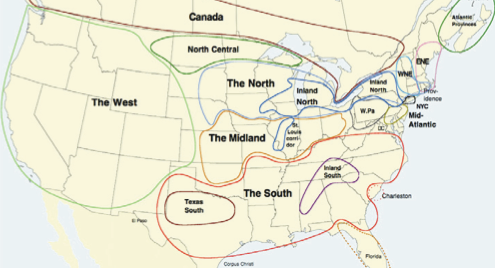

“It is counterintuitive, but at a national level we are not actually speaking more alike. Regional differences are becoming more pronounced,” he said. By regional, Kendall means the linguistic definition given to large swaths of U.S. territory, such as the mid-Atlantic, the South or the Midlands.

Kendall believes this phenomenon, like all language-change phenomena, has social and psychological origins.

Linguists divide the U.S. into dialect regions, with the western states lumped together as a single region that has no official dialect and (supposedly) no differentiation among states. But Tyler Kendall is researching the possibility of distinct dialects in Oregon.

“People are partial to where they are from, and they usually want to fit in with the local population. This orientation influences our speech patterns. What start out as subtle psychological nuances in word choice and sound eventually affect our dialect, changing it over time,” he said.

By listening to vowel shifts around the country, linguists are now concluding that many regional speech varieties are becoming more audibly distinct.

This trend has been particularly well studied in the inland North, a region linguists define as the lower peninsula of Michigan, northern Ohio and Indiana, the suburbs of Chicago, part of eastern Wisconsin and upstate New York.

“The English spoken by people in Chicago and the cities in the inland North generally sounds less like the English spoken in, say, Nevada today than it did even fifty years ago,” he said.

The studies have also shown change in dialect is happening much faster than linguists anticipated. “We are noticing sound shifts in language in a generation or less,” said Kendall.

With these trends in mind, Kendall is now turning his scholarly eye to Oregon.

“The assumption by many people is that Oregon, like the rest of the West, speaks an unmarked dialect,” he said. Otherwise known as a “broadcast standard” (the standard broadcasters like Brian Williams are trained to emulate), an unmarked dialect is one that defies attachment to a particular locality.

But Kendall thinks there may be more variation in the West—a territory linguists describe as the states west of and around the Rocky Mountains—than currently recognized.

A recent arrival from the East Coast, Kendall considers himself lucky to have landed in an area not much linguistically explored. He estimates there are only a handful of sociolinguists working in the Pacific Northwest, including himself.

As an informal first step toward building what he hopes will be a repository of recordings for formal analysis, Kendall has been recruiting students to record interviews with native Oregonian speakers. Each student then performs an acoustic analysis, transcribing the recording and using linguistic software to measure features of speech that might mark it as distinct, such as the acoustic characteristics of certain vowel sounds.

“We now know that language change is happening constantly and quite rapidly,” said Kendall. “What better way to study those changes than in the little-investigated area of our own backyard?”

—Patricia Hickson

Image from The Atlas of North American English, DeGruyter, 2005

Watch

Watch  Watch excerpts from the opera, coming soon to Eugene.

Watch excerpts from the opera, coming soon to Eugene.

Three’s a charm for a living memorial.

Three’s a charm for a living memorial.