Humanities

Humanities

Interview with the Vampire

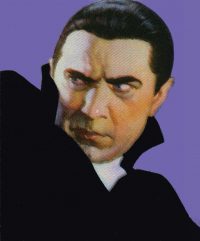

Author Bram Stoker’s Dracula is renowned for introducing the world to one of fiction’s all-time great monsters.

Author Bram Stoker’s Dracula is renowned for introducing the world to one of fiction’s all-time great monsters.

To introduce her comparative literature students to the Count, instructor Katherine Brundan asked much more of them than just a close reading of the book.

In an effort to transport students to Dracula’s 19th-century London, Brundan took full advantage of rare resources in Knight Library. Students dug into the digital versions of content first printed a continent away and more than a century ago—newspapers and other periodicals produced in London in the 1890s.

Each student first chose a periodical for the project. Then they wrote an article based on one of the story lines in Dracula, while trying to match the tone and style of their selected publication.

“The goal of this project was to immerse students in the journalism of the day,” Brundan said. “They had to think creatively about how to place the novel within the debates and language of its own era.”

One student wrote mock interviews with the main characters by incorporating direct quotes from the novel. Another adopted a “true crime” approach, writing up newspaper-style reports of the Count’s suspected misdeeds. A third reviewed the novel as if writing on the same day that it was first released.

Julianna Hollopeter, a freshman majoring in communication disorders, took the opportunity to get outside her comfort zone.

She penned an article for a conservative newspaper called The Spectator. Hollopeter attempted to defend an idea with which she personally disagrees—that the city’s women needed men to fend off Dracula’s attacks. She assumed the guise of a male reporter, making “his” case while she tried to imitate the stilted, flowery prose of the era with passages such as:

“Our women need protecting because they are delicate and easily manipulated against the powers of evil. Thus, strong, capable men need to keep watch and protect our faint-hearted ladies.”

As with the others, Hollopeter was expected to write historically accurate prose.

For example, Stoker emphasized in Dracula the dawn of “the new woman”—what we now know as feminism—through Mina Harker, a resourceful character who helps find the vampire even after falling under his spell. But because the word “feminism” was just emerging in 1890s Britain, Hollopeter wrote about the concept without referring to it by name:

“After speaking with Mina it was easy to see how she exhibits certain traits of the new woman. These characteristics include learning shorthand, practicing journalism, traveling on her own, and participating in non-normative activities.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Hollopeter said the project made her a better writer. But she also became a better reader.

“Now I look at a text and when it was written,” she said, “and instead of seeing it as a 21st-century woman, I can see it as it was supposed to be perceived back then.”

—Jim Murez

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Forward

Forward