Lessons in Life

Interview by Jim Murez

Before he joined the University of Oregon as an English instructor, Mike Copperman taught in one of the most demanding educational environments in America: a poverty-stricken area of the rural Mississippi Delta.

Fresh from college in 2002, Copperman (above, circa 2003) worked for the nonprofit organization Teach for America, serving as a first-time teacher in the public schools. His lofty goal was to offer underprivileged children an education that might help them find a path out of hardship.

But in a cash-strapped district beset by challenges, Copperman quickly found that he was lucky simply to make it to 3 p.m. each day without difficulties in his classroom that stopped his lessons cold.

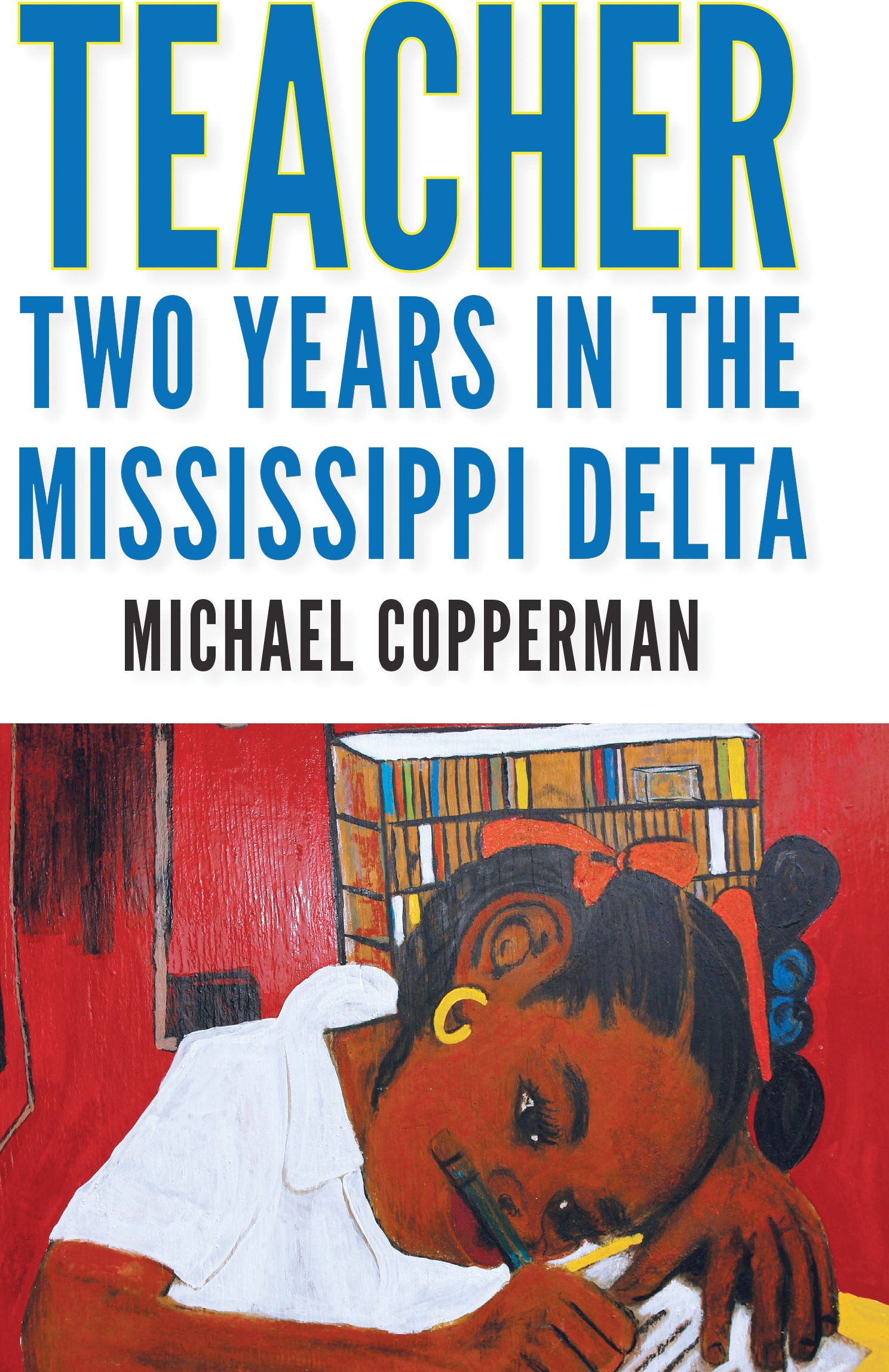

In his new memoir, Teacher: Two Years in the Mississippi Delta, Copperman recounts his experience as a young educator in over his head. He describes, in frank, vivid language, the promise and problems of his fourth-grade students and the colossal hurdles they faced at home and in the classroom.

Over a bittersweet two years, Copperman and his kids taught each other hard lessons about life, often inadvertently. But that knowledge serves Copperman today, as he teaches introductory writing to a diverse group of UO students who face challenges not unlike those of the kids he encountered 15 years ago.

Q: A girl you call “Felicia” was perhaps your favorite student—and also the source of your most painful experience. What was her story?

MIKE COPPERMAN: Felicia was brilliant; she had a near-poet’s tongue. She learned the basics of algebra without any real instruction in it. She was always the first to school and she helped me prepare the classroom for the day.

But she was having struggles at home. Felicia’s mother was with a boyfriend in Georgia, so Felicia and her brother had been living with their grandmother. Her mother came back, gathered her things and told Felicia that she was leaving for good. Felicia begged to go with her, but her mother said she didn’t ever want Felicia again, that she’d never wanted her at all.

That started Felicia on a downward spiral. It was her against the world—she began harming others and disrupting everyone’s opportunity to learn, harassing the most vulnerable students. I used every technique I could to get her back in line. But ultimately, she was expelled. Some kids told me recently that she’s incarcerated.

Q: Sounds like this was one of your many unexpected lessons.

MC: I was 23. Letting her go seemed like I was abandoning her, but I sacrificed too much trying to keep her in my classroom. When I recognized how much of my attention and energy had gone to her, I realized it was unfair to the other kids.

I should have let her go earlier.

Q: Felicia lashed out when she was expelled, disparaging you as being part of the “white establishment.” What do you feel when you think about her today?

MC: Sorrow. The world around Felicia wasn’t adequate to create someone who would grow up and be OK. It doesn’t make it right, but there was a kind of inevitability to what became of her. I remember asking the students once to write a paragraph about what Santa ought to bring them; Felicia wrote, “Someone to love who gone love me back.”

Q: You had another student, Serenity—perhaps the most challenged of all your kids—who ultimately succeeded. That must have been a very different kind of lesson.

MC: Serenity demonstrated to me that children are resilient beyond what I could have imagined.

She was from a family of extreme poverty. Holes in her khakis. She sometimes didn’t smell good because the water at her house was turned off. She was taking care of her younger brother almost full time. When asked where her mother was, she’d shrug—her mom was “always messed up,” the kids said. More than once I caught a child mocking her.

All Serenity wanted to do was read all day and escape the life she had. She would wall herself off with a beanbag chair in a corner where kids couldn’t get at her, and read. Harry Potter was her favorite—she liked the empowerment of the children, with the spells and the magic and their inevitable happy endings.

I was determined to reach Serenity, to give her a chance. I told her she was smart and bright and should just read and she was going to be successful. She went from a fourth-grade reading level to that of an 11th-grader during that year. She made the honor roll in high school and went to college. She is poised to go to graduate school to become a social worker and help people who are, she says, like she was.

I was talking with Serenity recently and she thanked me for that year, said it was different from her other years in elementary school, which all blurred together. I guess for her that year was formative.

Q: You characterized as “traumatizing” your experiences with corporal punishment. What happened?

MC: It was my philosophy that good teaching is good classroom management. But the schools there relied on corporal punishment. The assistant principal paddled kids, and he was a very large man. He used a three-foot-long paddle. It’s not spanking. It’s designed to inflict the maximum amount of pain.

At the height of my frustration at a particular point in my first year, and having a classroom full of children making animal noises day after day after day, I wrote referrals to the assistant principal for about 10 kids. They got 100 licks, altogether—the chalkboard was smeared with mucous from crying children.

There was one boy, Antiquarian, who always looked up to me. I remember him turning back and looking at me—he was being held responsible for something that I’m not sure he had even caused. He was a bright, animated, extremely troubled young man who was being abused at home, and I taught him that the world wasn’t just, the world goes to the strongest bully with the biggest stick. It will probably always stay with me.

Q: You wrestled with deep guilt over your role in paddlings. Have you forgiven yourself?

MC: I was in survival mode. The behavior of some kids was extraordinarily difficult—I write about a girl who could size up an adult in five minutes and say something which cut right to the heart of their greatest insecurity. I threw a child out of class who had spit in my face.

The inability to process much of what went on during the worst periods of my first year is part of what drove me to write this book. When I was in the middle of it, it was much harder to make those value judgments. It took me a lot of years to get at that convoluted mix of things that was true at the time, which is that I genuinely loved those kids, wanted to help them, wanted to teach them well.

“An artist painted the picture that I used for the book cover, and when I saw it, I thought, that could be Felicia. That is her at her best: doing work, and immersed in it, with so much before her. When I look back at her I can’t help but see the promise that she embodied.”

Q: What do you bring from teaching fourth grade in the Mississippi Delta to teaching introductory writing at the University of Oregon?

MC: I have a deep need, given what I saw in the Delta, to offer students what I can. The kids I teach now are very much similar to those kids in Mississippi. They’re low-income, first-generation students of color. There are no guarantees for a freshman from a disadvantaged background who has defeated the odds and has just gotten into college—they drop out of this institution at two to three times the regular rate. As I write in the book, each day in the classroom with these 18-year-olds, I imagine that I’m speaking directly to those kids for whom I wanted so much.

Q: Take us into the classroom with your 18-year-olds and their assignments.

MC: Each term, I teach two introductory writing classes, each with 18 freshmen. These are students who have been encouraged by the Center for Multicultural Academic Excellence to take the class. It’s a strategy to help these students gain a skill set and confidence, and connect with other students who are not a majority—they often will make friendships.

I’m having students discuss, question, relate, share and assess ideas in small groups and then individually. Then they write papers that take into account a variety of viewpoints, a close reading of different texts, the modeling of critical and analytical thinking and how that plays out as you’re doing a formal writing assignment.

We also explore identity. We consider texts in which writers write about their own identity: Zora Neale Hurston’s “How It Feels to Be Colored Me” and Langston Hughes’ “Theme for English B.” We’re reading for technique and literary qualities, and then the students write about their own experiences in identity. It gives students an opportunity to write from the heart about those things that are most important to them.

Q: What experiences do these freshman students write about?

MC: Growing up in migrant families, working from the age of 4 or 5 in the fields, and the tremendous responsibility of having your parents put their hopes and dreams onto you. I see students coming from low-income backgrounds, trying to reconcile the sense that they are leaving their families behind or that they are better than their families in some sort of way by seeking an education.

Sometimes they write about the violence they’ve been through. Or what their siblings have gone through. Or what their parents have gone through. These students carry a lot.

Q: What’s something you learned in Mississippi that you apply at the UO?

MC: There are almost always reasons why students act the way they do. Not excuses, but reasons.

I had a UO student whom I called Caron in the book. When I first saw him, he was sitting, arms crossed, slouched, backwards baseball cap. I had told the students I’ll call you whatever you want me to call you; he introduced himself as “Bad.” That was not really the identity I was looking to put onto someone.

His behavior was outrageous for the university level—speaking in the background every time I spoke, satirizing or commenting on it or knocking it, and refusing to exchange with me in any way. That threw me right back into the most traumatic experiences of that first year in Mississippi, but I knew how much worse classroom behavior could actually get, so I knew this was not that bad. And I knew that there had to be a reason that was underpinning his behavior.

In his final essay, Caron apologized to me and explained that that was how he responded whenever he felt out of his depth. He hadn’t been trying to be disruptive. He went on to talk about an experience that was foundational to him in the African country where he had come from: Soldiers had put a gun right up to his temple and told him to give away the location of his mother, father and brother. He had held onto that trauma, the shame of being willing to give everyone up.

Q: Any success stories among your introductory writing students?

MC: There are so many students who have gone on to tremendous success.

One person in particular is a young man from north Portland; he grew up in an immigrant community with mostly black people, at one of the lower-income schools. I remember watching him as he began to think critically about the world around him and where he’d grown up. We discussed the American dream, the promises America makes to immigrants and minorities, and the reality of what is actually available to them. He recognized the significance of the lack of facilities and classrooms and teachers in the high school he had attended.

That class was the beginning of his awareness and critical thinking. He joined Teach for America himself and was placed in East Los Angeles and won an outstanding teacher award. He’s a teaching superstar—he’s extraordinarily inspiring.

Q: Throughout Teacher, you wrestle with whether you were a success or a failure in Mississippi. How do you see it today?

MC: Having gone back recently and talked to my 22-year-old former fourth-graders, I realize that those years in the classroom made a tremendous difference. Not for the reasons that Teach for America would have assumed, not from a teacher’s perspective like “we did this curriculum” or “everyone achieved this level of proficiency on this test.”

It was a whole host of small things—a particular project, or the aggregation of all these days in which my classroom was a safe, comfortable, encouraging space where the students were told that they could achieve, and that achievement meant just trying.

Those years in the classroom saved no one from poverty or struggle. They didn’t lift those kids to success through one year of instruction. That’s not how education works. But my persistent belief in them, or the chance to play kickball with kids on a field on some sunny day, or the patience I somehow found to deal with a kid who was losing his temper—those small actions resonate in larger ways. Those things made a bigger difference than I knew.

Pseudonyms are used for students from Mississippi and the University of Oregon to protect their privacy.

Book cover: University Press of Mississippi

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Forward

Forward