Natural Sciences

Natural Sciences

Feeling It

The war in Syria has claimed more than 400,000 lives. But it was the image of a single dead child that made the world sit up and take notice.

The picture was of 3-year-old Aylan Kurdi, lying lifeless on a Turkish beach. He drowned in 2015 when the raft in which he and his family were riding sank as they fled the embattled country.

After the image was published, Google searches on Syria spiked and donations to charities and aid groups surged.

Given the passionate reaction to the loss of one child, why has the global response to hundreds of thousands of deaths been comparatively muted?

The answer, psychologists say, is “psychic numbing.” We’re moved by the loss of a single life but numb to many deaths because, as the numbers rise, we can’t fully comprehend them.

This idea was introduced in 2007 by Paul Slovic, a UO psychology professor, whose half-century of work in human behavior has earned him one of the highest honors bestowed upon US scientists. Slovic was recently named to the National Academy of Sciences, which advises the government on science and other matters.

Slovic studies why we act in certain situations—or don’t.

He found that the value we place on a human life drops as the number of lives at risk increases. This happens when even two lives are at stake; when the numbers reach hundreds of thousands, he says, we find them incomprehensible.

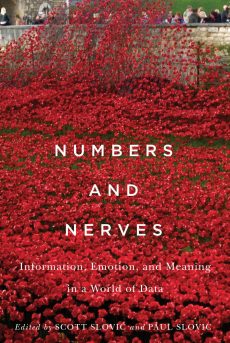

Slovic explains this phenomenon in a new book: Numbers and Nerves: Information, Emotion, and Meaning in a World of Data, coedited with his son, Scott, a professor at the University of Idaho. They explore why we’re desensitized by numbers (visit Slovic’s website, arithmeticofcompassion.org, to learn what to do about it)

When we can’t comprehend something, Slovic says, it’s difficult to know what to feel about it—and feelings drive our actions. Consider how we assess the risks of medical X-rays compared with nuclear power plants.

Slovic and colleagues found that the public ranked X-rays as lower in risk. But risk experts saw X-rays as riskier, based on their knowledge of radiation exposure.

Most of us trust our gut in these situations. We’re familiar with X-rays and find them beneficial, so we don’t fear them. But we generally know little about nuclear reactors and associate them with nuclear weapons—which prompts an uneasiness that tells us to steer clear.

This is “risk perception,” and Slovic is one of the most influential thinkers in the world on the topic, said Nicholas Pidgeon, a psychology professor at Cardiff University in Wales who also studies risk.

Pidgeon credited Slovic for a dozen or so key findings in risk, emotion and our fondness for “rule of thumb” decisions, calling his discoveries “world-leading advances.”

Said Slovic: “It is satisfying to apply my research findings to some of the most serious problems in the world today.”

—Jim Murez

—

Blockbuster author Michael Lewis (Liar’s Poker, Moneyball, The Big Short) is at it again—and this time he gets an assist from Paul Slovic.

In The Undoing Project, Lewis follows Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, two of the world’s most influential researchers in decision-making. They’re credited for the infusion of analytics into everything from baseball to presidential campaigns.

Slovic worked closely with both scientists. Lewis cites work by the trio in his book and, in the acknowledgments, writes that he is especially grateful to Slovic and others for a

“guided tour of the history of psychology.”

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Forward

Forward