Natural Sciences

Natural Sciences

Not So Fast: Concussions and Recovery Time

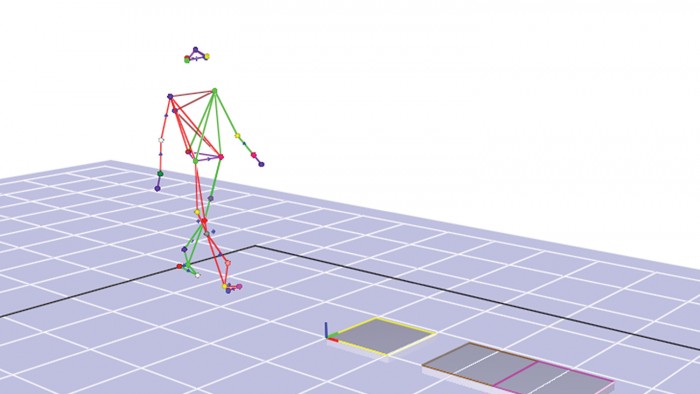

The testing for concussion recovery time took place in the Motion Analysis Laboratory, where researchers used cameras to capture signals from reflective markers on subjects’ bodies, to create real-time computerized imagery of the subject’s movements. Watch a video that shows the gait impairment of a high-school athlete with a concussion.

Boxers knocked to the canvas have ten seconds to get back on their feet. A football player who has had his “bell rung” might get five or ten minutes on the sideline before he’s ordered back into the fray. In either of these scenarios, popular medical thinking holds that, longer term, a concussion usually clears up within a week or so.

But last year, the UO’s Department of Human Physiology made a stunning find: The ability to focus and switch tasks was compromised for up to two months following brain concussions suffered by high school athletes—much longer than the seven to ten days previously thought.

Through an arrangement with Eugene-area schools, twenty high school athletes who had suffered a concussion—primarily football players but also others from soccer, volleyball and wrestling—were assessed within seventy-two hours of injury and then again one week, two weeks, a month and two months later. Each of the subjects, whose diagnosis was made by a certified athletic trainer or physician, was matched with a healthy control subject of the same sex, body size, age and sport.

Subjects were tested over a two-month period for their ability to respond to auditory cues while walking. The testing took place in the Motion Analysis Laboratory, where researchers use reflective markers on subjects’ bodies to create real-time computerized imagery of the subject’s movements. A recorded voice played over speakers in the lab said the words “high” or “low,” at pitches that were occasionally inconsistent with the word (e.g., a low-pitched voice might say the word “high”). The subject was required to identify the correct pitch, regardless of the word that was heard.

The findings showed that concussed subjects had more difficulty maintaining balance and walking speed while responding to the auditory cues.

Given most concussions can’t be seen on an MRI, examining a subject’s balance during this kind of “dual-task walking” might assist in assessing the injury and recovering from it, the team said.

“The differences (in response time) we detected may be a matter of milliseconds between a concussed person and a control subject,” said lead author David Howell, a graduate student in the department. “But as far as brain time goes, accurately measuring that difference is significant for determining if a linebacker will be returning to competition too soon—which could mean increased risk of another injury.”

Howell, along with professor Li-Shan Chou and professor emeritus Louis Osternig, also found that concussions affect the gait of adolescents who are asked to perform basic cognitive tasks while walking.

It’s believed to be the first-ever assessment of balance recovery in this high-risk group. Many of the 1.6 million to 3.8 million annual concussions nationwide are sustained by high school athletes, who may be more vulnerable to lasting injury because the frontal regions of the brain are still developing.

Dr. Viviane Ugalde, medical director for the concussion management program at the Bend-based Center Foundation, said the UO research shows that there can be limitations to conventional testing methods that base concussion recovery on neurocognitive response.

“Typically, kids will clear [those tests] within two weeks,” Ugalde said. “The interesting thing about the university’s study is that despite clearing their neurocognitive testing, subjects had this lingering difficulty with multitasking . . . showing that their function wasn’t normal even two months out. That’s a big deal in terms of us figuring out when it is safe to return kids to play.”

Ugalde encourages athletes and their families to participate in concussion studies so that researchers can pinpoint the amount of time necessary for recovery. Answering that question might involve a combination of tests that measure a subject’s neurocognitive response as well as balance and even their stride.

— Matt Cooper

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Forward

Forward