Students produce compelling documentaries that capture oral histories of the many paths of migration to Oregon.

Students produce compelling documentaries that capture oral histories of the many paths of migration to Oregon.

The tattoo on Lidi Soto’s forearm undulates from elbow to wrist. What could it represent? As you learn more about her—her origins, her research as a student at the University of Oregon, her current job as a liaison with migrant workers in Lane County— an idea begins to dawn: could it be a map?

Yes, Soto confirms. The tattoo is an outline of the state of Oaxaca, where she was born.

Soto’s family is one of thousands that have made the journey to Oregon from this struggling region in southern Mexico. Her family followed a path traversed by many Oaxacans: first traveling to Veracruz on the Gulf of Mexico, then to Sinaloa and Baja on the Gulf of California, and then eventually on to Oregon—ranging farther and farther north in search of work.

Soto, who graduated last spring with a degree in ethnic studies and political science, captured her family story in a documentary she produced in her final year as a UO student, for a unique class in ethnographic research called Latino Roots in Oregon.

The subject of Soto’s ten-minute film is her mother, Rosalina Morales, who recounts her personal journey from her hometown of Santa María Tindú to Scotts Mills, Oregon.

Morales first began migratory agricultural work when she was eight, going with her father to Veracruz to work the sugarcane fields. After she married, she continued to leave Tindú with her husband and children in search of seasonal work. Her husband eventually came to the U.S., but the money he sent back wasn’t enough to support the family, and he gradually brought the oldest children to Oregon, then his wife and remaining children (including Soto).

As a child, Soto worked the fields around Mt. Angel with her family for many summers.

“I came here with the intention of staying two years,” her mother says at the beginning of the video. But she did not return to visit Tindú until eighteen years after coming to the U.S. (photo below).

Years in the Making

The Latino Roots course, offered for the first time in 2011 and now again in 2013, has been several years in the making. One of the first milestones in its development was a 2009 exhibit produced and curated by anthropologist Lynn Stephen, College of Arts and Sciences Distinguished Professor, and Gabriela Martinez, associate professor of journalism, which focused on the underrepresented history of Latinos in Lane County.

The educational panels created for the exhibit—originally displayed at the Lane County Museum and now traveling around the state—documented the lives of Latinos who have populated the county for generations. Stephen and Martinez also conducted several oral histories, including video interviews, which were an integral part of the exhibit.

These activities created a model for the students who would soon be enrolling in a unique course developed by Stephen and Martinez, also called Latino Roots. Both the course and the exhibit are sponsored by Selco Community Credit Union.

The Latino Roots course is a two-term intensive in cultural anthropology, ethnography and documentary filmmaking that culminates in a capstone video project documenting an individual or family history.

Cotaught by the two professors, the class introduces students to an alternative narrative to the white pioneer history of Oregon, examining the depth and breadth of Latino and Latin American immigration, settlement, social movements and civic and political integration in Oregon during the twentieth century.

So far, this might seem like the syllabus for any of a number of courses in ethnic studies, anthropology or history, but some key points of departure make this a singular class.

Self-Interrogation

On a very personal level, students in this class are asked to also examine their own histories. Where did their parents come from, what are their roots? The purpose is to make them better aware of the differences among themselves, as well as their unexplored biases, to prime them to go out into the field to take another person’s oral history.

“The first step of investigation is to ask oneself the same questions that will be asked of others,” said Stephen.

Because the first cohort of students came from a wide range of ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds, disclosing their personal histories in class led to searching discussions about racism, stereotypes, privilege and other challenging topics.

At the midpoint of the first term, the emphasis then shifted from this immersion in history, context and personal perspective to practical matters. Students began to learn how to research archival materials, how to conduct an oral history, how to master the basics of audio and video recording. In other words, they were delving into the methods of ethnography, steeped in the big questions of the practice, such as: Whose side do you tell a story from? What is truth? What is fact? What is the line between fiction writing, history and ethnography?

Only a select group of students was invited to enroll. “Students hear about it and they think it sounds really cool, especially because of the documentary capstone project,” said Stephen, “but it’s actually twice as much work as a regular class.”

To ensure that the students who enrolled were committed—and also able to handle the intellectual and technical aspects of the class—Stephen and Martinez interviewed all students interested in signing up. They accepted twenty-two, eighteen of whom saw the class through to completion.

Building on the foundation of the first term, the second term is highly technical. It’s essentially a crash course in documentary filmmaking—production planning (aesthetics, lighting, framing sound); creating, building and refining the rough cut; adding music and subtitles; hours and hours in the Cinema Studies Lab at Knight Library, using Final Cut Pro, fine-tuning a final version.

The end result is a “digital portfolio” that contains the student’s documentary as well as a transcript and selected pictures, documents and other source materials— all of which contribute to the Latino Roots in Oregon project and become part of University Archives and Special Collections at Knight Library.

Deportation Nation

Byron Sun had Eleven hours of interview footage with his parents to trim down to ten minutes. Like Soto, he was born outside the U.S. and originally came into the country without documentation.

When he was a toddler, Sun, a native of Guatemala, came to the U.S. with his mother to join his father; they were transported by a “coyote.” At the beginning of his documentary Deportation Nation, Sun recounts this journey in a voice-over, narrated over a stream of family photos and depictions of life in his home country:

It took us over a month because the coyote wanted to sexually abuse a younger woman in the group. The train helped us escape, taking us closer to the border and to the hands of another coyote. “¡Aaaa-puuu-ren-se!” Darkness . . . the smell . . . the rats . . . the American Dream . . . the sewage tunnel dumped us in San Isidro; La Migra arrested us; they stripped us of our clothes checking for drugs; a few days went by and we got bailed out by my father.

But Sun and his mother did not show up for their immigration hearing; instead they stayed in the U.S. undocumented for seven more years. He grew up as a bicultural kid in Van Nuys, California, speaking Spanish at home and English at school, celebrating birthdays with piñatas and dressing up for Halloween as a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle.

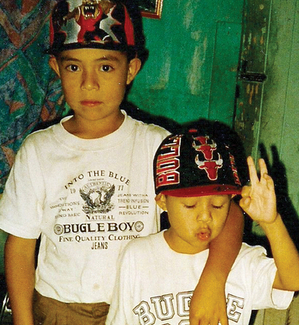

And then they were deported. Sun’s U.S.-born younger brother (shown with him in the photo, above) left the country with them.

Having been Americanized, Sun now had to re-acculturate to life in Guatemala City, witnessing the daily perils of street violence, drugs and poverty but also more peaceful moments: “[from] the clapping of hands covered in masa making tortillas, to the blessings that I got from elderly women, to the hundreds of people walking in the streets talking.”

Four years later, Sun and his mother received a pardon, which enabled them to return to the U.S. legally. Sun was uprooted once again and re-entered life in the States—this time in Oregon, where his father now lived.

Sun, who graduated last spring with a degree in ethnic studies and Spanish and is now in a bilingual creative writing program at the University of Texas, considers himself “a transnational human,” with roots in both the U.S. and Guatemala.

“What I can’t find in one part of my identity,” he said, “I can find in the other.”

In Daily Conversation

Not everyone in the Latino Roots class focused on their own family. Other students interviewed friends and acquaintances.

Scott Erdman, for instance, interviewed “Aurora López,” who had been his coworker at a food processing plant in Eugene. He gave his friend a pseudonym and also filmed her so that her face is never revealed, protecting her identity because she is in the process of seeking citizenship.

In the video, López is shown in daily conversation with her family in Tulancingo, Mexico, where her father and six of her siblings live. Taking advantage of cheap international cell phone rates, she chats during her lunch break at work and also at home while engaged in everyday tasks such as frying tortillas.

In one conversation with her father, he recounts first coming to the U.S. in 1940 as a bodyguard for General Miguel Flores Villar of the 26th Mounted Regiment of Mexico. After World War II, he came back as part of the bracero program, which brought five million agricultural workers into the United States between 1942 and 1946 (photo, above). He picked oranges and cotton in Texas, but then was deported—along with his wife and two U.S.-born daughters— under “Operation Wetback” in 1954.

Eventually, the two daughters who were U.S. citizens returned to the United States and helped two of their sisters (including López) come to Oregon. When López decided to leave Mexico to find work, she travelled by bus to Tijuana, where she met one of her sisters and they went to meet a man at a bar.

Her sister told her, “You leave with the guy and I’ll see you on the other side.” The man drove her to a drop-off location and López crossed the desert on her own. She made her way to Klamath Falls to work the potato fields with her sister, and then they both moved to Eugene, where López earned a GED at the UO.

Knowing What They Are Facing

Erdman uses the skills he acquired in this class every day. After earning his degree in Latin American studies last spring, he was hired as a legal assistant for an immigration law firm in Eugene. In this capacity, he works directly with individuals and families—many of them from Oaxaca—who are trying to adjust their legal status, extend their visas or avoid deportation. This often means creating a narrative that conforms to the requirements of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

In the Latino Roots class, “I learned how to guide someone through the process of telling their story,” Erdman said. And while the storytelling in his professional life must conform to what the CIS requires, “it’s similar to guiding a subject through to a coherent story line,” as he did in producing his documentary.

The cultural knowledge Erdman gained through the course has been invaluable, too. “I took away an understanding of transnationals,” he said, “especially knowing what they are facing if they go back.”

At the end of the course, Erdman’s video—alongside those of his peers in the Latino Roots class—was shown at a public celebration at Knight Library, when their digital portfolios were officially made part of University Archives and Special Collections.

The videos are already being used to educate the next generation. Spencer Butte Middle School in Eugene, for instance, incorporated the videos—as well as the Latino Roots exhibit—into a day-long Latino Festival last November.

And in a very personal turn of events, a UO ethnic studies professor is now showing Lidi Soto’s documentary in one of his classes.

This brings it full-circle for Soto, who just a few years ago was sitting in a UO class about immigrants and, during the viewing of a video about farmworkers, was very surprised to recognize some of the workers in the film. Now the documentary is hers and the story is hers to tell.

-Lisa Raleigh

-thumb-200x200-1722-thumb-100x100-1723.jpg)

From federal forest payments to the benefits of reading readiness, econ honors projects get real.

From federal forest payments to the benefits of reading readiness, econ honors projects get real. SPUR student receives prestigious Howard Hughes Medical Institute Award.

SPUR student receives prestigious Howard Hughes Medical Institute Award.