Lots of students change their majors. They spend a year or two on campus going down their chosen path and then they take, say, a geography or linguistics class to get a requirement out of the way—and lightning strikes. A new world opens up and they are off in an unexpected direction, inspired with fresh energy and enthusiasm.

Joseph Bitney did this before even taking a single class as a freshman. He originally declared a major in human physiology, aiming to become a physical therapist. But after he registered for classes in chemistry and physics, “I went online and looked at my class schedule,” he recalled, “and I thought, ‘Is this what I really want?’”

He thought about his passion for film and literature and how much he had loved his advanced English classes in high school, and this led him to consider a different future as a teacher or college professor.

After talking it over with his parents, he switched his major to English. “They told me they could see I was so passionate about it, they knew right away that it was a good choice for me,” he said.

It’s been a good choice indeed. Now a junior, Bitney, a Clark Honors College student, has distinguished himself as a standout among English majors.

Among his many accomplishments, he received a 2012–13 Undergraduate Research Fellowship from the UO Center on Teaching and Learning. The URF funds three undergraduate research fellows per year, providing a full-tuition waiver in support of their projects.

One of the rarities

Over the years, most URF recipients have been students in the sciences, a few in the social sciences and fewer still in the humanities. Bitney is one of the rarities in a humanities field.

He has given serious thought to the difference between humanistic and scientific research. In lab science, he says, there’s an existing protocol for the discipline. But in the humanities, “you have to establish your own protocol,” he said.

In Bitney’s case, figuring this out meant spending last summer reading everything he could that pertained to his general topic: ethnic American poetry. He read Native American, Latino, Asian American and African American poets, as well as critics, essayists and biographers.

For poets from previous generations, there is often a body of scholarship that serves as a guidepost along the way, but for more contemporary poets, their creative work is the only reference point. Because Bitney was left to his own devices to discern what was worthy of attention, “it was kind of nerve-racking,” he said, “but a lot more interesting” than following a codified procedure.

Bitney’s fellowship will focus on the responsibility ethnic writers feel to their communities and the ways that politics and literature intertwine. He discovered his enthusiasm for this topic in a poetry course last year. His paper for that class, “The Incomparable Horrors of Lynching,” won the English department’s 2012 Swig Essay Prize.

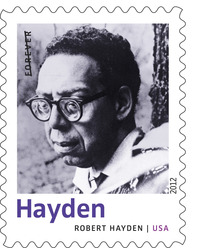

Bitney has decided to work on three projects this academic year (one per term) rather than a full-year project and single terminal paper, the option usually chosen by URF fellows. For his first term, his focus was African-American poet Robert Hayden, whom Bitney characterizes as “neglected in both popular and critical terms.”

Hayden was writing at the time of the black nationalist movement in the 1960s but did not politicize his poetry—i.e., he did not use it as a vehicle for expressing overtly political views.

“He was more nuanced than that,” said Bitney. “He did his research. He had a complex view of history. He was also a member of the Bahá’í faith.” As a result, Hayden’s poems, such as “Middle Passage,” which dwells on the journey of slaves across the ocean, “have an interesting tension between his refusal to deny the horrors of the past and his impulse to universalize,” said Bitney.

In other words, Hayden’s work could be said to depict the human condition, not just a particular race. This meant he didn’t neatly fit into the “black poet” category and was therefore overlooked.

But a smaller corpus of scholarship and criticism can be a good thing for a budding scholar. In Bitney’s case, it means he has more opportunity to determine his own approach, make his own interpretations and draw his own conclusions.

And that’s what research is all about.

-Lisa Raleigh

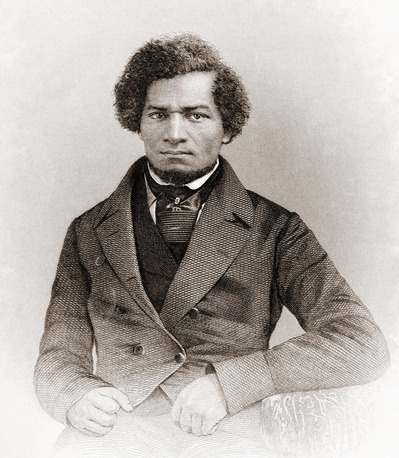

Frederick Douglass

By Robert Hayden

When it is finally ours, this freedom, this liberty, this beautiful

and terrible thing, needful to man as air,

usable as earth; when it belongs at last to all,

when it is truly instinct, brain matter, diastole, systole,

reflex action; when it is finally won; when it is more

than the gaudy mumbo jumbo of politicians:

this man, this Douglass, this former slave, this Negro

beaten to his knees, exiled, visioning a world

where none is lonely, none hunted, alien,

this man, superb in love and logic, this man

shall be remembered. Oh, not with statues’ rhetoric,

not with legends and poems and wreaths of bronze alone,

but with the lives grown out of his life, the lives

fleshing his dream of the beautiful, needful thing.

Robert Hayden, “Frederick Douglass” reprinted from Collected Poems of Robert Hayden, edited by Frederick Glaysher. Copyright © 1966 by Robert Hayden. Reprinted with the permission of Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton.

-thumb-200x200-1722-thumb-100x100-1723.jpg)

From federal forest payments to the benefits of reading readiness, econ honors projects get real.

From federal forest payments to the benefits of reading readiness, econ honors projects get real. SPUR student receives prestigious Howard Hughes Medical Institute Award.

SPUR student receives prestigious Howard Hughes Medical Institute Award.