When a bilingual speaker switches between one language and another, what motivates the switch? That was the essential research question for Sarah McCauley ’12, who double-majored in linguistics and Spanish.

When a bilingual speaker switches between one language and another, what motivates the switch? That was the essential research question for Sarah McCauley ’12, who double-majored in linguistics and Spanish.

To explore this question, McCauley designed her own study centered on the phenomenon of “code switching,” the linguistics term for switching between languages. Code-switching might involve a single word, a phrase, a sentence or an entire conversation.

Not surprisingly, McCauley found that the Spanish-English speakers in her study switched languages depending on context—i.e., they changed it up depending on who they were speaking to and the topic of conversation.

Affiliations and Aspirations

But she also discovered that many other factors came into play: where the speaker was born and grew up, family heritage, social affiliations and aspirations—even physical appearance.

In fact, this latter determinant had a profound influence: to what extent did the speaker believe he is perceived as Latino? And how strongly did he want to be perceived as such?

In other words, it’s complicated.

For her study, which she submitted as her Clark Honors College thesis, McCauley recruited four Latino bilingual speakers from the UO student population, all of whom happened to be male. She first conducted an interview with each of them—in either English or Spanish, depending on their preference—to get their personal histories, and then she paired them up for one-on-one conversations that were digitally recorded.

McCauley was not present for those paired conversations, but suggested that the participants discuss whatever topics they liked (sports, family, school and so on) and speak to each other in English or Spanish or both in a way that seemed most natural.

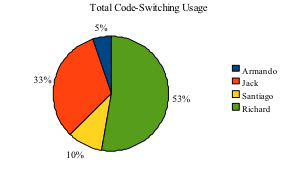

From the interviews and recordings, she analyzed their individual patterns. How often did each person initiate a switch from English to Spanish or vice versa? Did the switch involve occasional words or phrases, whole sentences or long passages? When one speaker switched, did the other follow? She then charted and graphed their behavior.

"It's really about the why"

But the pie charts (right) didn’t give her answers; they only raised more questions. “I thought it was going to be about the data,” said McCauley. “But it’s really about the ‘why’.”

Why, for instance, did “Armando” speak primarily English—in all contexts?

Armando (a pseudonym) was born in Eugene, the first in his family to be born in the U.S. His father is Mexican, his mother is Dominican and his skin tone is dark. He grew up in a bilingual household, where both his mother and his uncle spoke only English to him. Today, he primarily uses English, even with his family, and he chose to speak English in the interview with McCauley, stating that he could express himself better in this language.

But another reason for preferring English, he revealed, is his sense that others perceive him as “black,” not Latino. This has led to awkward social interactions when he speaks Spanish and so he avoids using it. Because of his skin color and the way he perceives others respond to him, “his struggle is proving he’s not really black,” said McCauley.

As a result, Armando has lost confidence in his Spanish skills, so that when he was paired with “Santiago” for his one-on-one conversation, he spoke minimal Spanish in that context, even though Santiago moved fluidly between languages.

Santiago was born in Mexico but raised in Los Angeles. His father, of Italian descent, and his mother, of Lebanese descent, were also born in Mexico and spoke Spanish in their home when Santiago was growing up. In fact, he did not learn English until he started school in the U.S.

Immersed in the Latino community in Los Angeles, he grew up fully participating in the traditions of his Mexican roots and still considers himself to be part of this culture.

In conversation with Armando, Santiago initiated numerous switches from English to Spanish, but Armando would reply with only very brief answers in Spanish, and Santiago eventually abandoned the effort.

Crossing and recrossing boundaries

This contrasts with the other pair, “Jack” and “Richard,” who easily crossed and re-crossed the Spanish-English boundary in their conversation.

Like both Armando and Santiago, these two men also trace their family histories back to multiple countries.

Jack was born in California and grew up in a bilingual household. While he did not give many specifics about his family heritage, he said his ancestors came from several Latin American countries, including Ecuador. He views bilingualism as a strength and thinks of himself as a “world citizen.”

Richard was also born in California, to a father of Italian descent and a mother born and raised in Mexico, and grew up in Eugene. He learned both English and Spanish in his home and considers himself, like Jack, to be truly bilingual, reliant on the two languages equally.

McCauley notes that both Jack and Richard are light-skinned and so can “pass” as Caucasian; however, both have consciously chosen to embrace their Latino identity and purposely use language to reinforce this. Richard, in particular, deliberately uses Spanish among his friends “by way of proving that he’s not just another gringo,” said McCauley.

Intensely personal

So what determines when a Spanish- English bilingual speaker chooses to use one language or the other? This small sample of four provided McCauley a glimpse into how intensely personal each person’s circumstances and motivations can be.

There was an additional complicating factor for the men in her study, McCauley noted: the surrounding culture—i.e., the Anglo-dominant community of Eugene, where less than eight percent of the population is Hispanic or Latino. Yet even that was not a universal influence, as revealed by Armando and Richard, who both grew up in Eugene but demonstrated very different patterns of language use.

All of this led McCauley to conclude that generalizations can go only so far. “Every person brings with them a unique experience and attitude,” she said.

-Lisa Raleigh

-thumb-200x200-1722-thumb-100x100-1723.jpg)

From federal forest payments to the benefits of reading readiness, econ honors projects get real.

From federal forest payments to the benefits of reading readiness, econ honors projects get real. SPUR student receives prestigious Howard Hughes Medical Institute Award.

SPUR student receives prestigious Howard Hughes Medical Institute Award.