Humanities

Humanities

Life of Lyon: A Digital Diary

You’ve never heard of the writer A. S. Lyon. He wasn’t a member of the 19th-century literati like Austen, Dickens or Wilde. He was just a young man living in London’s East End in the 1820s and ’30s, trying to find his way. He labored to start a business and climb the social ladder. He traveled. He clashed with his brother. He endured debt and illness.

A. S. Lyon was fascinated by the arts and wrote frequently in his diary about visits to museums, historic houses and the theater. English major Rachel Elkins created a digital research exhibit that explored the contexts for Lyon’s theater excursions and literary interests. During her examination, Elkins found a document relating to poet Emma Lyon, sister of the diarist; it provided evidence that Emma Lyon was nominated to become the recipient of charity funds for literary figures. The discovery came as a surprise to Lyon descendants who have spent years studying family history.

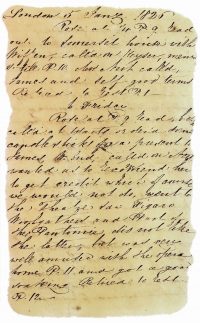

Writing was his release. Lyon kept a diary from 1826 to 1839, chronicling his trials and travails as he futilely pursued entrepreneurial success and happiness. The diary survived through the years, passed down from one descendant to the next, generation after generation. Forty pages long, more than 20,000 words—about a third of the length of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Careful cursive penmanship on paper yellowed by time, an intimate account of the internal struggles of an everyday person living an everyday life, almost 200 years ago.

In other words, a literary gold mine for scholar Heidi Kaufman.

Kaufman, an associate professor of English, studies the writing of 19th-century residents of the East End, an area of London infamous for seedy and sensational depictions of poverty and crime. When she came across the Lyon diary during the course of her research, Kaufman saw an opportunity to take a creative leap—to engage her students in a demanding project that would combine the latest digital technology with traditional investigative methods in the humanities.

The result is a dynamic website called The Lyon Archive. Launched earlier this year, the archive offers a sweeping exploration of A. S. Lyon’s life charted by Kaufman’s students, who have become tour guides to a world that they have created through their contributions to the digital archive. They read and reread the text, determining how to offer an online presentation of what the diary reveals about the life and times of a single individual.

To provide context to names, places and ideas referenced in the diary, students scoured online resources, collecting nearly 100 images and other graphics for the archive. They analyzed the diary using the latest web-based tools, forming arguments about subtexts embedded in the text—depression, travel, education, theater, love—and presented their cases via multimedia “exhibits” that are an essential part of the archive.

Kaufman’s course on the Lyon archive, made possible through a grant from the Oregon Humanities Center, offers one example of “digital humanities” scholarship—DH for short.

According to Kaufman, DH is a field that integrates critical thinking and literary analysis with digital technologies. In creating a digital archive in her class, students learn how to read a text closely, analyze data, produce a multimedia “essay” and conduct research on websites and databases. These are 21st-century skills that will serve them well no matter what future profession they pursue.

Other aspects of the project were equally important to Kaufman and her students.

The website, for example, is public; students rose to the challenge of creating an attractive, online resource that will be useful for scholars and anyone else with an interest in 19th-century literature.

“Knowing that someone other than their professors is reading their work raises the stakes,” Kaufman said. “That ability to showcase their efforts to the public is one of the most exciting features of digital work in the humanities.”

Finding a British Ship

It was one word in a 20,000-word diary. But junior Clay Davenport (left) knew immediately that it was important: Britannia.

26 Tuesday

Quite busy with the intended departure of Hart and his lady for England. At 4 o’clock went with them on board the Britannia, Cap. Phillips. Took my leave of them with sincere prayers for their safe arrival in England.

Like his classmates, Davenport (below) was tasked with interpreting key elements of a 190-year-old diary entry that offered no obvious clues. Although the diary has been transcribed from Lyon’s cursive handwriting, it’s no textbook—there are no chapters, n o explanatory notes, no table of contents, no index to peruse for important ideas and topics. It’s a raw, unprocessed piece of writing.

o explanatory notes, no table of contents, no index to peruse for important ideas and topics. It’s a raw, unprocessed piece of writing.

Kaufman trained the students how to examine the text critically. After reading the 40-page diary end-to-end, they went back through, meticulously listing names of people, places, events and activities that might offer clues for deeper understanding.

Davenport realized that travel was a theme, so rereading the text yet again, he drew new meaning from the entry mentioning a ship named Britannia. The author was in Barbados at the time, seeing his brother off for a return to England; Davenport decided to look online for information about the vessel that could be added to the archive to provide context for readers of the diary and for classmates creating multimedia essays.

From digital technology workshops, Davenport had learned about the limitations of various web resources in the hunt for content.

He knew that for his purposes, Google would be ineffective—it would be unlikely that information about an obscure ship from 1820s Europe would rise to the top of search results. Instead, he tried a UO Libraries database that pulls web content relating to the 19th century; his search for “Britannia ship” produced dozens of newspaper clippings and other materials specific to the vessel in question, moving Davenport’s research forward.

The more he searched, the more Davenport realized that he wanted an image—a way to visualize what travel was in 1826. That led him to a website called Wikimedia Commons, a popular repository of free images, audio and other media. After just a few minutes of refining his search, he found it: an image of a beautiful oil painting of the very ship mentioned in the diary—the West Indiaman Britannia, a merchant vessel (pictured at top of page). A perfect addition to the archive.

To post the item online, Davenport had to learn the inner workings of the web-based publishing platform, Omeka, that Kaufman used to build the archive. As a part of that task, he added to the image more than a dozen descriptive elements—called “metadata”—including a title for the item, the source, a description of its relevance to the diary and his own name as the contributor.

Once he had finished, Davenport sat back for a moment and tried to put himself in the place of the author, looking up at the ship as it set sail for a weeks-long journey across the Atlantic.

A sense of satisfaction washed over him. A cinema studies major, Davenport considers himself a storyteller; he had felt obligated to put everything he could into the archive project, entrusted as he was with the responsibility of interpreting a person’s writing and experiences based on fragments of observations recorded in his personal diary. Finding the ship was well worth the trouble.

“We were documenting someone’s life and bringing it to life,” Davenport said. “I wanted to tell his story as if, 200 years from now, somebody else was telling my story.”

Detective Work

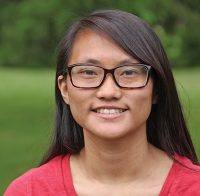

The thought of becoming a detective intrigues Mai-Ling Maas (below). She’s got a knack for investigation.

Maas, who graduated earlier this year as valedictorian of the English department, created one of the archive’s research “exhibits”—that is, a multimedia presentation that showcases students’ interpreti ve claims about the text.

ve claims about the text.

Maas argues in her exhibit that Lyon suffered from depression caused by business woes, and that his frequent travels—a form of therapy—could be understood within an emerging medical debate about the proper treatment for mental illness. It took a lot of detective work to get there: pulling apart the evidence—the 40-page text—and analyzing it for subtle indications and concrete evidence that he struggled with despair.

One key to developing her premise was Maas’ use of one of UO Libraries’ online databases, which enabled her to dig deep.

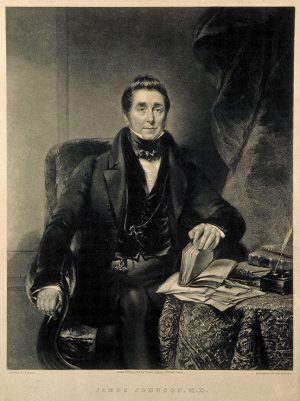

Working from Lyon’s mention of a visit to a physician named James Johnson, for example, Maas developed a rich profile of this popular “People’s Doctor,” (right) who treated psychological problems. She tapped a library database collection containing 19th-century materials to capture Johnson’s role in establishing depression as a serious mental malady that couldn’t be resolved simply with a change in diet and activity.

“Lyon was switching from one doctor to another right at the moment of a larger debate about which treatment is better. Mai-Ling illuminated an emerging school of medical thought,” Kaufman said. “It was only through her research into ‘the blue devils’ and the doctors Lyon visited that she was able to understand the diary in a whole new way.”

Maas also made her case by using innovative, web-based applications for literary analysis.

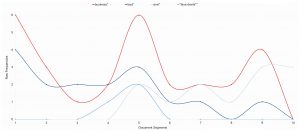

Using Voyant Tools, a free digital resource that analyzes texts, Maas identified—in seconds—connections between words and ideas throughout the 20,000-word diary. She discovered, for example, a close correlation in the proximity of the words “business” and “anxiety” or mention of the phrase, “blue devils,” the latter being the era’s colloquial expression for feelings of depression or melancholy; this became the basis for Maas’ contention that Lyon’s entrepreneurial failures drove his mental anguish.

Maas used the web-based tool Voyant to analyze the diary for connections between word frequency in the diary and allusions to Lyon’s depression. For example, in the above visualization, she found a high correlation between the words “business,” “anxiety” and “blue devils,” which led her to theorize that the author’s entrepreneurial failures contributed to his depression.

Voyant, like other web applications designed for textual analysis, builds upon traditional approaches to literary research, according to Kaufman.

“Tools like Voyant don’t replace close readings of the text,” she said. “When you visualize a text with a digital tool like Voyant, you pick up things that might have escaped the eye. It’s like putting on a different pair of glasses.”

With her research and conclusions in hand, Maas faced the challenge of how to present her work in a compelling, easy-to-follow multimedia essay. She couldn’t simply post a traditional essay online and ask readers to start at the beginning and continue to the end; she had to organize her argument into succinct, stand-alone but interlinked webpages, each containing the context and background necessary for understanding her larger argument.

Images were essential to that presentation. Like a magazine, websites are designed to integrate words and images in creative, informative ways; accordingly, Kaufman graded these digital presentations based, in part, on whether the visual elements—images, charts and other graphics—“drew out” the text and helped to support the essay’s claims.

Repeated references in the diary to “blue devils” indicated a state of melancholy and sadness. Noticing this was the beginning of Maas’ investigation into whether the author struggled with depression; she included an image of an 1826 etching (above center) on the archive website.

In her project, for example, Maas needed images to support the premise that Lyon battled his depression by occasionally removing himself from the pollution of 19th-century London. She found just the thing to capture the city’s filth: a striking political cartoon, created just a few years after Lyon kept his diary, depicting the River Thames as a source of cholera and other diseases. The value of the image became clear to Maas when she learned about 19th-century fears about the spread of disease and the rise of epidemics in Lyon’s East End neighborhood.

For Kaufman, these “digital research essays” exemplify the usefulness of today’s technology in aiding understanding of a text.

“We need to think about the benefits and risks of our cultural shift from paper to digital media,” she said. “With this project, students had to think critically about the methods available to us to study literature and how those methods might be useful for one project and not for another.”

Lyon lived near the Thames River. As shown in the cartoon below, the Thames was associated with many diseases, such as cholera. The cartoon was published in a weekly British satirical magazine from the 19th century.

Maas said the project was “like solving a mystery.” She can’t say for sure that her future is in detective work, but she’s confident that she’ll be conducting investigations in whatever career—business, marketing, publishing—she pursues.

“I really enjoyed the research,” Maas said. “And I can incorporate research into a lot of different jobs.”

—Matt Cooper

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Forward

Forward