Natural Sciences

Natural Sciences

The Work of Breathing

For Dillan Firestone, it took only one lecture from a UO professor to set her on the research path.

Originally a biochemistry major, Firestone (right) was in the College Scholars program when she took part in a freshman colloquium with a guest lecture by human physiology associate professor Andrew Lovering. These one-credit courses introduce students to different facets of academic research, and Lovering’s lecture focused on his research on cardiopulmonary respiration.

Originally a biochemistry major, Firestone (right) was in the College Scholars program when she took part in a freshman colloquium with a guest lecture by human physiology associate professor Andrew Lovering. These one-credit courses introduce students to different facets of academic research, and Lovering’s lecture focused on his research on cardiopulmonary respiration.

Fascinated, Firestone approached Lovering and asked if she could come and observe some of his experiments. By the end of her freshman year she had changed her major to human physiology and was working in Lovering’s lab—not something every freshman gets the chance to do. Not long after that, she was conducting research for an undergraduate thesis that enabled her to graduate with departmental honors.

(Curious what kind of jobs a degree in human physiology can lead to?)

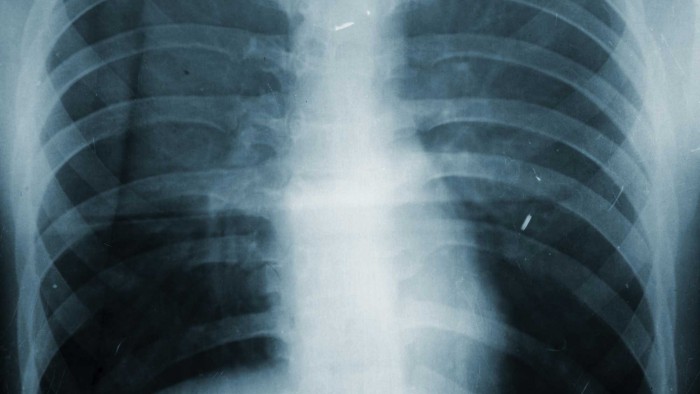

Firestone’s project looked at the long-term effects on lung function among those born prematurely, particularly the effects on a person’s ability to exercise.

Researchers already knew that people born prematurely, defined as those born at least eight weeks early, generally have a lower capacity to exercise. Those later weeks of pregnancy are a vital period for lung development, and being born early can leave children with impaired breathing function.

Exercising to exhaustion

What isn’t well understood is the exact nature of the impairment. Studies had shown that children born prematurely could move gas in and out of their lungs just as efficiently as full-term children, so Firestone looked at the basic ability to take in air, known as the “work of breathing.”

Working closely with Lovering’s postdoctoral fellow J. J. Duke, she and a fellow undergrad, Carly Celebrezze, recruited two groups of college students, one that had been born prematurely and another that had not. They put them on stationary bikes and, breathing room air, had them exercise to exhaustion.

Then they repeated the experiment, only the subjects were breathing a mixture of helium and oxygen, a gas known as heliox. The difference was striking.

“The preterm subjects could exercise for a longer amount of time while breathing heliox than they could when breathing room air—about 25 percent longer,” Firestone said. “That tells us that heliox significantly reduces their air restriction.”

The heliox breathing gas seems to make the work of breathing easier for the subjects whose lungs were affected by premature birth, but it had no effect on those who were born at full term. That suggests that one long-term effect of being born prematurely is difficulty taking in air, a finding that formed the core of Firestone’s thesis. Other researchers will have to refine the conclusions before a possible therapy can be considered, but Firestone said it’s a step forward.

“It lets us understand the implications of being born early and the potential complications that can persist into adulthood,” she said.

Lovering said Firestone has been an excellent student who fit in very well with his lab team. Lovering likes bringing younger undergrads into his lab so they can learn from older students and get an early start in tackling actual research.

“All of our research requires a team effort, and Dillan has been an important part of that team,” Lovering said. “My approach has worked well for us . . . because I have been fortunate enough to work with students like Dillan.”

Firestone has a pretty good idea of where her next stop will be, but it’s not the one she was planning when she first arrived on campus. Back then, her goal was a medical degree. But that was before the number of years that would take really sank in.

“I realized that’s a lot of school,” she said. “I decided I wanted to do something that was almost the same thing, but with less school.”

So she’s shifted her focus, and now has her sights set on becoming a physician’s assistant. But she needs to log some clinical experience before she can start applying, so last fall she started working at a Eugene care center while she finished up her degree in human physiology.

Firestone said she plans to keep the job for another year or two before applying to schools in Northern California or Arizona that are offering a physician’s assistant program. And with both clinical and research experience under her belt, she’s optimistic about reaching her career goal.

While she doesn’t plan to make research her life, she said the experience was invaluable. If nothing else, it gave her a ringside seat to the process that produces all those books she has to read as a student.

“It’s allowed me to appreciate how much work and effort goes into the research process,” Firestone said. “I guess I didn’t realize how much time and energy goes into everything that we’re reading.”

—Greg Bolt

Photo of Firestone: Greg Bolt

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Forward

Forward