Passages

The loss of loved ones often comes too soon. So it was with the abrupt passing of three from the College of Arts and Sciences late last year, leaving the university in mourning and remembrance.

Read obituaries for geographer Susan Hardwick, creative writing professor Ehud Havazelet and English alum Lawrence Levine.

Remembering Susan Hardwick, Educator, Mentor and Scholar

In November, the university lost geography professor Susan Hardwick at age 70, after a brief illness.

In November, the university lost geography professor Susan Hardwick at age 70, after a brief illness.

Hardwick, who joined the UO Department of Geography in 2000 and retired in 2010, is remembered for her passion, enthusiasm and longtime dedication as a teacher, mentor, advisor, researcher and national leader in the field of geography education.

Even in retirement, she continued to teach two courses each year, mentor graduate students and future teachers and serve as co-director of the UO’s summer graduate program in geographic education.

“Susan’s tireless efforts, her innovation in creating new programs and her capacity to build bridges where other people saw chasms, have given her a special place in the pantheon of scholars who have changed education.” said W. Andrew Marcus, interim dean of the College of Arts and Sciences and a professor of geography.

Hardwick’s career began in 1968, with a teaching job in a one-room schoolhouse in Oroville, CA. She went on to earn an MA in geography at Chico State University and spent the next thirteen years teaching geography at a community college in Sacramento. Following the completion of her Ph.D. at UC Davis in 1986, she went on to become a geography professor at universities in California, Texas and, ultimately, Oregon.

In recognition of her extraordinary service and leadership in advancing geography education, Hardwick was honored in 2013 with the George J. Miller Award for Distinguished Service, the highest award given by the National Council for Geographic Education.

“It is hard to name any major development in geography education over the past few decades that does not in some way bear Susan’s imprint,” said her colleague Alec Murphy, professor of geography and Rippey Chair in Liberal Arts and Sciences. “She was a tireless and effective champion of the cause.”

Among her many accomplishments, Hardwick played a critical role in crafting the original and revised versions of the National Geography Standards and cohosted the hugely successful PBS-Annenberg series, The Power of Place. She also spearheaded the development of an online training program for teachers of AP Human Geography, and played a central role in bringing to fruition the Road Map for the Large-Scale Improvement of K–12 Geography Education.

Key to her success, said Murphy, was “her ability to convey her enthusiasm to those around her. Susan had a tremendous influence on a range of students and teachers throughout her career—encouraging them to take up and advance the cause.”

Her numerous other accolades included the Distinguished University Educator Award from the National Council for Geographic Education and the Outstanding Professor Award for the entire California State University System. She was twice awarded the UO Rippey Innovative Teaching Award.

Hardwick published several scholarly books, two college textbooks, one middle school text and scores of articles and book chapters, and also authored a number of pedagogical works, including Geography for Educators: Standards, Themes, and Concepts, a text that has been used by several thousand teachers-in-training over the course of the past two decades.

Her professional service contributions were legion, said Murphy. Most notably, she served the National Council for Geographic Education as president and vice president of research and external relations. At different points during her career she sat on the national councils of both the Association of American Geographers and the American Geographical Society—taking the lead on many initiatives for those organizations. She was also an active member of the editorial board of the Journal of Geography for more than a decade, and she was a great contributor to other professional organizations in the U.S. with a geographic remit, including the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers and the National Geographic Society.

She also made significant contributions to the literature in cultural-historical geography, with a particular emphasis on the evolving ethnic geography of cities in the United States and Canada. She is widely known for books on Russian refugees in North America (University of Chicago Press, 1993) and the role of immigrants in the making of Galveston Texas (Johns Hopkins University Press), as well as scores of articles on the ways in which racial and ethnic differences have shaped North American urban landscapes. In recognition of her contributions, the Ethnic Geography Specialty Group of the Association of American Geographers bestowed its Distinguished Scholar Award on Hardwick in 2001.

“Professor Hardwick’s good heart, her passion for her work and her intellect have impacted literally tens of thousands of students and teachers from kindergarten through graduate school through in-service training for experienced teachers, many of whom never knew that Susan was the force behind their experiences, ” said Marcus. “We will miss her terribly, but take solace in knowing that her influence lives on in so many ways.”

Ehud Havazelet, 1955-2015, “Fiery, Brilliant, Unstinting”

Also in November, the university grieved the death of creative writing professor Ehud Havazelet at age 60.

“Ehud was an engrossing and demanding teacher, who loved being in the classroom and attended to every aspect of writing from the comma to the cosmic,” said Karen Ford, associate dean of humanities and professor of English. “He could make a discussion of sentence mechanics riveting and an explication of a Flannery O’Connor story transforming.”

Havazelet, who joined the UO faculty in 1999 to teach fiction, was a two-time Oregon Book Award winner—in 1999, for his short-story collection, Like Never Before, and again in 2008 for his novel Bearing the Body.

His work was also nationally acclaimed, with honors such as the Guggenheim Fellowship, Rockefeller Fellowship, Whiting Writers Award and Pushcart Prize. Two of his books were named New York Times Notables and his story “Gurov in Manhattan” was included in The Best American Short Stories 2011.

Havazelet is remembered as both a master craftsman and passionate teacher. In a tribute on the creative writing homepage, UO poetry professor Garrett Hongo characterizes his colleague as “fiery, brilliant, unstinting, mercurial, and very, very loving of our students and our shared enterprise of creating lasting work.”

“Havazelet will be remembered for the beauty and precision of his writing and for his generosity as a teacher and friend,” wrote staff writer Jeff Baker in a remembrance in the Oregonian.

Ford recalls that Middlemarch was Havazelet’s favorite novel, and “like Middlemarch, Ehud was capacious and complex—brilliant, learned, tender, funny, ironic, cynical, hopeful,” she said. “In my last conversation with him, tenderness prevailed.”

Havazelet received a BA from Columbia University and an MFA from the Iowa Writer’s Workshop. He was named a Stegner Fellow at Stanford University and went on to teach at Oregon State University before coming to the UO.

He was diagnosed with leukemia in 2002 and received a bone marrow transplant, living with the aftermath of cancer treatment until his death in November from complications of pneumonia. A memorial will be held at 2 pm March 12 in the Knight Library Browsing Room.

Read Ehud’s obituary in the Corvallis Gazette Times. Please visit an online tribute site.

In Memoriam: Lawrence Levine

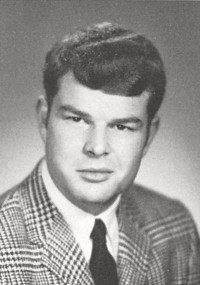

In October, Lawrence Peter Levine, who earned two English degrees here, was killed in a shooting at Umpqua Community College.

In October, Lawrence Peter Levine, who earned two English degrees here, was killed in a shooting at Umpqua Community College.

Lawrence Peter Levine, 67, was an assistant professor of English at UCC, which allowed him to share his passion for writing with others. He was a writer first and foremost, according to an obituary in The Oregonian, and he completed numerous novels—including a mystery set in the Northwest called Timber Town—but none was published.

Born in Manhattan, Levine grew up in Beverly Hills and, after graduating from high school, moved to Oregon. He moved back to California in the mid-1970s and joined UCC a few years ago, where teaching was a secondary occupation to his work as a fly fishing guide, the newspaper reported.

Private services were held early in October. Levine is survived by a sister, Joanne Levine Press, who lives in California.

At the UO, Levine received a bachelor’s degree in 1969 and, in 1972, a master of fine arts in creative writing. Though his novels were never published, Levine’s rich contribution to the university community is preserved in his MFA thesis, “Collected Works: 1969-1972,” available in the Knight Library.

Some of this early material shows flashes of a light, playful imagination. In “The Game, for Toronto Atwell,” Levine writes:

Tell me of Chicago and Bo Jangles;

the night, after a game at Paddy’s,

Ethel Waters gave a party.

Tell about the nine ball that fell,

the crumpled hundred dollar bill,

the hot nights in Philadelphia,

the cold ones in Minneapolis.

It was not just the money you won,

having the good fortune to be where Billie Holiday was singing

(and Lena Horne walked in).

But a somber, melancholy feel—even a touch of darkness—runs through much of it. In one poem, Levine describes a poet reading his work, for the first time “no longer scared of failing in my art.” In another—“An Insomnia of Destination”—night brings an old refrigerator that “sounds like machine guns shooting down clowns bouncing at the penny arcade” while something in the distance moves closer.

“Owl’s wisdom hereditary” ends jarringly: an owl sets its glowing eyes upon a swan in a dark pool “with its neck tied in a knot.”

In another section of the collection, “Toward Fiction,” Levine explores the rougher edges of existence: embarrassment, suffering, desolation. Short stories describe a man carrying a naked corpse across the desert and another in a suit of armor, enduring unbearable heat, stopping for a drink of water and then clanking on stoically toward a burning red sunset.

The last entry in the collection is “Cinematic Piece no. 1/The Magician and the Clown,” which Levine wrote in the form of production notes for a vaudeville magic show.

He describes the magician’s movements as “crisp and disciplined,” his smile “cold and condescending, and … frozen on his face throughout his act.” The magician is handsome but the clown has a “piecemeal” face and eyes “seemingly devoid of comprehension.”

As the scene unfolds, the clown wanders from one side of a stage to the other, increasingly confused and vexed by the audience’s various reactions to his wild gestures.

Then, the magician enters. He walks up to a closet and opens the door, signaling for the clown to enter. The clown is timid, slightly cowering, but with the magician’s fatherly reassurance, he enters cautiously.

The lights darken and are brought back up slowly, the door is opened and the clown is revealed to be standing inside. He exits and continues his routine as if nothing has happened, but now his wild gestures bring only silence.

The clown tries harder and harder to create a reaction, to no avail. He quickly passes through all the familiar stages of loss: shock, confusion, anger and, ultimately, with a melancholy sigh, acceptance. As the scene ends, Levine describes the clown as alone on the stage and seeking refuge, but with nowhere to hide:

“Clown turns and walks toward closet. He stands in front of it and tries to open the door which has closed since his exit. It is locked. He nods his head consentingly, but tries door again, more boldly. Still locked. He scratches his head. Shrugs his shoulders, sighing deeply on their downward movement. Clown sits in front of closet, legs folded inward, back to audience/camera.

Lights dim to black.”

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Forward

Forward