Natural Sciences

Natural Sciences

Brain Trust

It’s no secret that childhood experiences can affect us well into adulthood.

Children who grow up in chaotic and unstable settings often struggle in school. They’re more likely to battle depression and addiction than others.

In fact, our experiences determine how our brains develop. Consider compulsive overeaters: the brains of those with this disorder have developed in unusual ways—there are actually different structures in some areas of the brain.

But the path of brain development isn’t set in stone in childhood. Brains can—and do—change throughout a lifetime. New neural circuits—the tiny electrical pathways that carry information across this organ—can form throughout childhood, into adolescence, and even well into adulthood.

With the right tools, it’s possible to build new pathways that can help people improve their lives.

A new UO research center is creating a roadmap of this cerebral superhighway, and it will provide training on how to reroute neural patterns to steer us to healthier decisions. The goal? Enabling people to short-circuit behaviors like addiction and aggression, developing innovative approaches to treating and preventing health and mental health problems, and informing public policy and programming.

The Center for Translational Neuroscience will translate knowledge about brain structure and function into practical tools for improving well-being.

Led by Phil Fisher, a psychology professor and Philip H. Knight Chair, the center unites researchers from neuroscience, psychology, education, and other disciplines. This cross-disciplinary mix is essential, Fisher says, because the knowledge in these fields is expanding rapidly.

“To really move the needle in any of these areas,” Fisher said, “you need people who are both really deep experts in their particular disciplines and who also find it enriching and compelling to engage in the kind of cultural exchange the center fosters.”

The center will assess strategies used to encourage healthy behaviors—say, improving the feel of visitation rooms where biological parents meet and bond with their children placed in foster care.

In one project, Elliot Berkman, a social psychologist and the center’s associate director, is trying to make a difference for teenagers with histories of drug use or unsafe sex.

Working from a pool of at-risk teens, Berkman has created two groups: those who grew up in stressful, unstable settings, and those who didn’t. He will run both groups through brief training sessions on a computer; the sessions are short games in which the user must stop rapidly pressing a button in response to a cue—a challenging task that requires self-control.

In some cases, the teen will see a picture of a peer during the session; in others, a neutral object such as a chair. Unbeknownst to the participants, they’re more likely to exhibit self-control or restraint when there are pictures of peers on the screen rather than neutral objects. Berkman’s hypothesis is that simply introducing the image of a peer at that critical moment when a teen is practicing self-control can improve the functioning of areas in the brain that manage impulse control in the moments when teens make their riskiest decisions: with peers.

Berkman is studying whether the training will affect the neural circuitry of the teens in both groups similarly, or if one group will experience greater changes. His team will review MRI brain images taken before and after the trainings to answer research questions.

(Berkman is also fascinated with the idea of self-control – or lack thereof.)

Along with helping people in the community, the center will help students in the classroom. Plans call for training available at every level, from undergraduates to those pursuing postdoctoral work.

“What we’ll be studying in the next 10 or 15 years will probably be something that hasn’t occurred to anyone yet,” Berkman said. “We need to give students the skills to go out into those fields and become effective collaborators.”

—Kit Alderdice

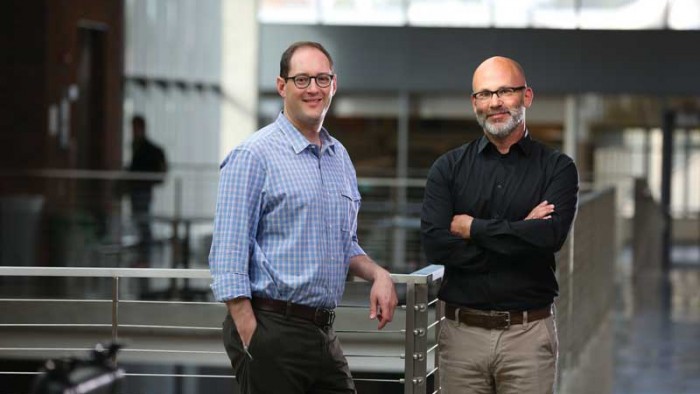

Photo caption: Berkman (left) and Fisher have created a center that will move nimbly, pursuing many smaller-scale projects rather than a single undertaking that would take years to complete.

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Forward

Forward