Humanities

Humanities

Repressive or Progressive?

The Chinese government recently enacted a law that, to Westerners, might seem a bit curious: Adult children must visit their aging parents.

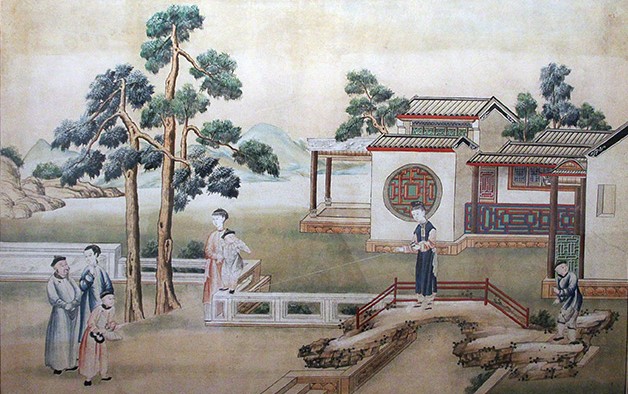

It was the formalization of perhaps the most fundamental virtue of traditional Chinese society. “Filial piety” refers to the expectation that children will honor their parents, maintaining a lifelong bond with them that historically has included extraordinary personal sacrifice, intimate caretaking and elaborate mourning rites.

Centuries-old tales abound—of sons tasting medicine to ensure its safety for their mothers or eating only foraged vegetables so that their parents may dine on rice.

It survives to this day: A Chinese newspaper recently reported that a 26-year-old man had pushed his wheelchair-bound mother for 93 days to reach a popular tropical tourist destination, calling it “by far the best example of filial piety” in years.

Modernization in China and a booming economy have raised concerns that children are beginning to neglect this sacrosanct practice. That has prompted resurgence in support for filial piety, and this is of particular interest to Maram Epstein, associate professor of Chinese in the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures.

Epstein’s new book—Orthodox Passions: Filial Piety in 18th-Century China—will be among the first to explore the changes in how this virtue was perceived at the verge of modernization. She is attempting nothing less than to rewrite the history of emotion for the world’s most populous nation.

Many modern scholars have treated with cynicism the accounts of filial piety from that era, dismissing it as a repressive and empty ritual requirement.

Epstein’s research, however, has convinced her that sons and daughters in Late Imperial China took seriously their obligations to mothers and fathers, in part because it allowed them to avoid other societal trappings—including romantic attachments—and to develop a sense of individual purpose. “Filial piety enabled people to resist other ritual demands,” Epstein said, “for example, that they dedicate their energies to serving as officials, husbands, brothers or wives.”

Some acts of filial piety may seem quaint or extreme to modern Western sensibilities, but they can be understood more positively within a discourse of love, Epstein said. Just as contemporary US culture affirms sacrifices made in the name of love (think Leonardo DiCaprio in Titanic or organ transplants made by a parent for a sick child), Epstein’s book will argue that China’s filial children were similarly motivated by powerful feelings of love.

Her book, to be finished this academic year, has been more than a decade in the making. In support of this project, Epstein has received a UO Humanities Center Fellowship and a summer stipend from the National Endowment for the Humanities, which underwrote her most recent research trip to China.

As her book nears completion, Epstein is sharpening her argument about what’s at stake if scholars begin to take filial piety more seriously.

If the practice is viewed as beneficial to—not repressive of—one’s sense of self, Epstein says, scholars—and perhaps even the rest of us—might be encouraged to rethink their interpretations of this tradition.

—Matt Cooper

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Forward

Forward