Humanities

Humanities

Immortal Beloved

“The death of a beautiful woman is unquestionably the most poetical topic in the world.” —Edgar Allan Poe

This shocking sentiment is perhaps not so shocking, considering the source. Who better than Poe, the master of macabre storytelling, to ponder—in characteristically creepy fashion—the intersection of beauty, death and poetic expression?

But the beauty of the dead woman is not the romanticized obsession of a lone nineteenth-century writer. This is made clear in the syllabus to a new lower-division course called Living Dead Girls, to be offered for the first time this winter by the Department of Comparative Literature.

Developed and taught by graduate student Rachel Eccleston, the course invites students to examine tales of dead girls throughout the centuries, starting with the Renaissance poet Petrarch and his immortalization of the lovely, deceased Laura to the twenty-first century novel The Lovely Bones, in which a dead teenager narrates her own story.

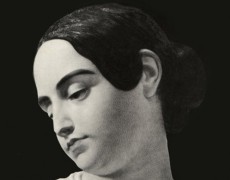

Along the way, other readings will range from Poe and his dead love objects such as Annabelle Lee (his wife Virginia, above, was said to be his inspiration) to critiques of the television series Twin Peaks, which centers around another dead Laura and the murder-mystery theme: “Who killed Laura Palmer?”

Eccleston is intrigued by the fact that the literary motif of the deceased young woman persists over time and well into our modern age. Yet she points out that the “agency” of the dead girl has transformed over the centuries. By this she means that deceased women in literature of the past were more commonly memorialized in rhapsodic tones by male admirers, with no voice of their own.

“The idea that women are most beautiful when they’re dead is so disturbing in so many ways,” said Eccleston. “The implication is that they are most beautiful when they are silent, mute and ineffective.”

But modern dead girls are more often in charge of their own narratives—like the teenager in The Lovely Bones. To a lesser extent, Laura Palmer in Twin Peaks gets her own voice in the afterlife when a cousin who looks just like her (played by the same actress) appears on the scene.

Eccleston also includes in her syllabus “living dead” examples such as The Dybbuk, a 1914 play in which a young bride is possessed by an evil spirit, causing her to act like a man (i.e., like someone who has more agency, or autonomy) and “Lady Lazarus,” a poem by Sylvia Plath, narrated by a reluctant survivor of near-death experiences who vows to prevail over her oppressors in the end. A Spanish story from the Renaissance era, “La Inocencia Castigada,” concerns a young woman who is turned into a sex-seeking zombie and then punished by her family, but who ultimately attains freedom and justice.

Eccleston particularly likes to include texts from centuries past because they can be a surprising revelation for undergraduates. “They assume that because a text is old, it’s boring. But they get to discover that it can actually be quite modern.”

— Lisa Raleigh

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Forward

Forward