The Outsiders

Daniel Wojcik was a child when he first encountered the art of the untrained.

During trips, his family was always stopping at one roadside attraction or another. He was amazed by the famous Watts Towers of Los Angeles, made of rebar and concrete and reaching 90 feet into the air; Bottle Village, a collection of shrines and mosaic walkways in Southern California composed of landfill discards and found objects—25 years in the making—left him fascinated and wanting to learn more.

Gregory Van Maanen, Untitled, 2009. Acrylic on board, 29 x 23 in. (73.7 x 58.4 cm). Courtesy Cavin-Morris Gallery, New York.

It was the art of the self-taught: people who didn’t even call themselves artists and had no formal artistic training, but were compelled to create. Often living on the fringe of society, they were labelled “outsiders”—psychiatric patients and visionaries, recluses and trauma victims.

Now Wojcik has returned to them, as an academic. In his new book, Outsider Art: Visionary Worlds and Trauma, the professor of English and folklore studies combines exhaustively researched profiles of these artists with stirring, revealing examples of their work. He tries to humanize those he says are frequently misunderstood.

Images from Outsider Art are featured on the following pages, with summaries drawn from Wojcik’s profiles of artists. He explores how these individuals use art to cope with adversity and trauma.

There is a tendency among enthusiasts of this genre to romanticize the artists’ suffering and pigeonhole them as deviants because it may make this type of art more desirable, Wojcik said. By telling the artists’ stories, he seeks to provide a better understanding of them.

Wojcik has occasionally used folklore to examine ideas outside the mainstream—this is someone, after all, who studies cultural beliefs tied to the apocalypse. But in exploring “outsider art,” he hopes to show that these artists are not so different from everyone else.

“Artistic expression,” Wojcik said, “is a universal human endeavor.”

GREGORY VAN MAANEN

Gregory Van Maanen, Happy Survivor, 1982–89. Mixed media on wood. Courtesy of Cavin-Morris Gallery, New York.

For Gregory Van Maanen, painting is nothing less than “a suicide prevention program.”

Born in 1947, the New Jersey native was a young soldier in Vietnam in 1969 when, during an attack, he saw fellow infantrymen killed next to him. Van Maanen himself was shot and left for dead; rescuers later found him, and he spent months in a hospital before returning home. War so traumatized him that he never talked about it.

But with painting and sculpture, Van Maanen releases the scenes in his head. The skulls and ghosts and nightmarish figures that he creates are his medicine, a way to cope with post-traumatic stress disorder.

MADGE GILL, 1882–1961

Madge Gill, Untitled, n.d. Ink on paper, 25 x 10½ in. (63.5 x 27 cm). De Stadshof Collection, Museum Dr. Guislain; www.collectiedestadshof.nl.

Gill’s life was beset by adversity. She was born in the 19th century out of wedlock and hidden away by her mother; she grew up in foster care, a girl’s home and an orphanage. As a mother herself, Gill lost two children, almost dying of complications during delivery of a stillborn baby girl. She suffered severe illnesses that required the removal of her left eye and all of her teeth; she endured emotional collapse and a failed marriage.

In creating drawings as large as 30 feet in length—and sometimes producing more than a dozen designs in one day—Gill worked in what others described as a trance state. She was guided by a spirit named Myrninerest, perhaps derived from “my inner rest.”

Over a 40-year period Gill produced thousands of drawings, yet the same image unfailingly appeared: a woman with a distant gaze in her eyes, a delicate nose and tiny lips, and often in a fashionable hat. Gill said that each of the faces she drew had meanings, but she never specified what they were.

HOWARD FINSTER, 1916–2001

One of the most famous outsider artists in the United States, Finster is known for thousands of paintings, sculptures and the two-acre “Paradise Garden” that he created in his backyard in Pennville, Georgia: a maze of sculptures and structures constructed from broken televisions, abandoned automobiles, discarded bicycles, water heaters, plastic toys and more.

Howard Finster, The Seven Devils, 1981. Tractor enamel on wood, 22 x 30 in. (56 x 76.2 cm). Photograph Jim Prinz. Courtesy of the Arient Family Collection.

Like a number of other visionary artists, tragedy visited Finster in childhood. He lost five brothers and sisters, including one brother who died gruesomely in front of Finster’s eyes, in a grass fire.

Howard Finster, A Feeling of Darkness, 1982. Tractor enamel on wood, 20¾ x 34 in. (52.7 x 86.4 cm). Photograph Jim Prinz. Courtesy of the Arient Family Collection.

In adulthood, Finster was a born-again Christian and minister. He was painting a bicycle one day when he suddenly saw a small face in a smudge of white paint on his fingertip; a divine feeling told him to “paint sacred art,” he said, and he soon created thousands of pieces.

Much of Finster’s art bears out apocalyptic beliefs about global nuclear annihilation and societal decay in the face of evil and suffering. He described visions of traveling to other planets and called himself “a stranger from another world.”

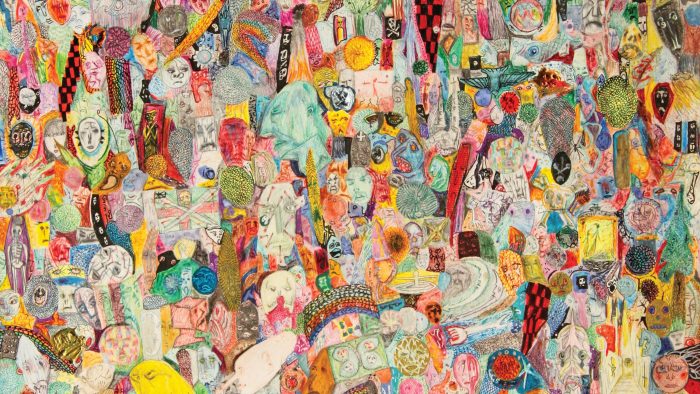

Nick Blinko, Untitled, c. 1998. Colored ink on paper, 16½ x 11½ in. (42 x 29.2 cm). Courtesy of Henry Boxer Gallery.

NICK BLINKO

Blinko, born in 1961, is the former lyricist and lead singer for Rudimentary Peni, a legendary British punk band. Diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder, his intensely detailed drawings arise from what he has described as “acute psychic anguish,” suffered when he is not on medication and expressed in tortured faces, skulls, tiny monsters, broken dolls and other haunted imagery.

Therapeutic drugs ease Blinko’s suffering but disrupt his concentration and hand-eye coordination. Without his medication, he has said, he is able to make the art that he desires—but the cost is full exposure to emotional pain and delusional states.

—Matt Cooper

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Forward

Forward