The Very First Folio

When the playwright Ben Jonson dared to publish a collection of his own works in a hefty volume called a folio, some viewed it as pretentious, if not way out of bounds.

It was 1616, the year William Shakespeare died. King James ruled England, the plague was still a threat and theater was considered lowbrow entertainment—disreputable, vulgar, immoral. Venturing into the hurly-burly of South London to attend a theater performance was to risk disease and exposure to criminals.

At the time, the notion of collecting dramatic works into folio form was, well, “a bit of a provocation,” said UO professor Ben Saunders, during a public lecture that was part of the UO’s celebration of Shakespeare’s First Folio.

Folios were beautiful, ornate, formalized printings of the highest forms of literate expression—typically the classics in their original Greek and Latin, and the works of esteemed theologians and historians.

The dissonance of printing plays in a folio volume would be analogous, says Saunders, to collecting the best creations of one of today’s comic book authors and binding them in an ostentatious tome, more suited to the collected works of canonical authors taught in literature classes. (Not coincidentally, Saunders is director of the UO’s comics and cartoon studies program, which elevates the study of comics to serious scholarly inquiry.)

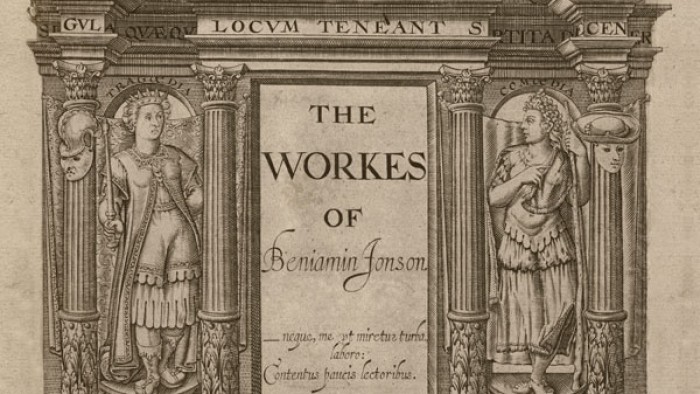

But the audacious Jonson was undeterred, determined that the literati take his writing seriously. Despite his status as a lowly scribe, his bold vision to self-publish The Workes of Benjamin Jonson—which included plays, lyric poetry and “court entertainments”—proved a pivotal milestone in legitimizing drama as an art form.

Jonson’s cause was advanced significantly by the publication of Shakespeare’s First Folio seven years later. With the passage of time, both dramatists ultimately earned the legitimacy that Jonson sought.

Jonson is now recognized as striking the first blow for the importance of theater as literature—and for pioneering the concept that the author is the definitive source of a play’s official text.

—Lisa Raleigh

Photo: Special Collections and University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Forward

Forward