Whole Lotta Shakespeare Goin’ On

In the opening scene of King Lear, the king grandly announces that he will divide his kingdom among his three daughters. But how he divides it will depend on which one loves him most.

The two eldest daughters rush to outdo each other with over-the-top declarations of adoration. But when the king turns to Cordelia (the youngest, his favorite), she refuses to play along.

The king is astonished and offended. Taken aback, he warns that her lack of cooperation may “mar her fortunes.” In other words, if she doesn’t make nice, she may get nothing when he parcels out all of Britain to his girls.

But does the king say that Cordelia’s words will cause him to disinherit her? Or does he more pointedly say that Cordelia herself is the problem?

It depends which version of William Shakespeare you’re reading.

A recent performance at Eugene’s Hult Center for the Performing Arts centered on two variations of the famous playwright’s King Lear: a “quarto” version (a transcript from an actual performance that took place in Shakespeare’s lifetime), and the official “folio” version (published after his death as part of an authoritative collection).

This one-time performance was not a production of King Lear, but a play about that famous play—and about the differences in how it could be performed.

The staging was simple: Five actors sat on chairs on the stage. In front of them were music stands on which they set their play scripts. There were no other props, no scenery, no costumes.

The actors were members of the renowned Oregon Shakespeare Festival company, and they were playing actors who were beginning a “table read” of Lear—in other words, their first run-through of the script together.

This play-within-a-play, entitled Sweetly Writ, was created and performed by the OSF in collaboration with the UO to demonstrate intriguing variations in Shakespeare’s work over time. The actors followed a script mainly aligned with the Lear published in the “First Folio”—a collected volume of Shakespeare’s plays that established him as a literary master.

But they also consulted an earlier quarto for reference. Line by line, the two versions varied in places by just a word or phrase, but sometimes entire sections were completely revised, omitted or added.

Lear can be portrayed as wistful, tyrannical, deranged or self-righteous; the other characters can be similarly nuanced. Which words will create the right mood for this particular performance, the right dynamic between the characters?

The actors discussed the line in question. The quarto version reads as follows:

How, how, Cordelia? Mend your speech a little,

Lest it may mar your fortunes*

But they decided on the folio version, which varies by a single word and more ominously pins the blame on Cordelia herself:

How, how, Cordelia? Mend your speech a little,

Lest you may mar your fortunes*

* emphasis added

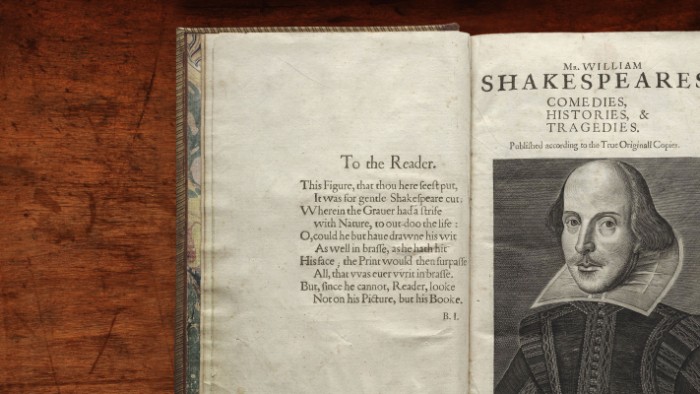

This year marks the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death. To celebrate the bard’s vast influence on our language and culture, the Folger Shakespeare Library launched a competition to choose a single location in each state to host a commemorative exhibit featuring Shakespeare’s First Folio (above).

The First Folio—formally titled Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies—is a milestone book, representing the first published collection of 36 of Shakespeare’s plays. An estimated 750 copies were originally printed; 233 are known to exist, and the Folger Library possesses 82 of them. (Learn more with First Folio: By the Numbers)

Of the 36 plays in the First Folio, 18 had never been printed before, including As You Like It, Macbeth, The Taming of the Shrew and The Tempest. Without this publication, these works might have been lost to history. And without the collection to spur lasting interest in Shakespeare, many more of the plays—until then, printed in flimsier editions called quartos—might have disappeared as well. Because of this landmark book, all have become a part of our literary heritage.

The Folger Library, based in Washington, DC, has sent 18 of its copies on a cross-country tour throughout 2016. Among the first stops: the University of Oregon. The UO was selected as the sole Oregon site thanks to a remarkable collaboration among several units on the UO campus and also the Oregon Shakespeare Festival.

“That we won out over other sites in Oregon—especially Portland—is remarkable,” said Karen Ford, associate dean for humanities in the UO College of Arts and Sciences. “Our selection speaks to our commitment to making humanities relevant and communicating their value.”

The Book That Gave Us Shakespeare

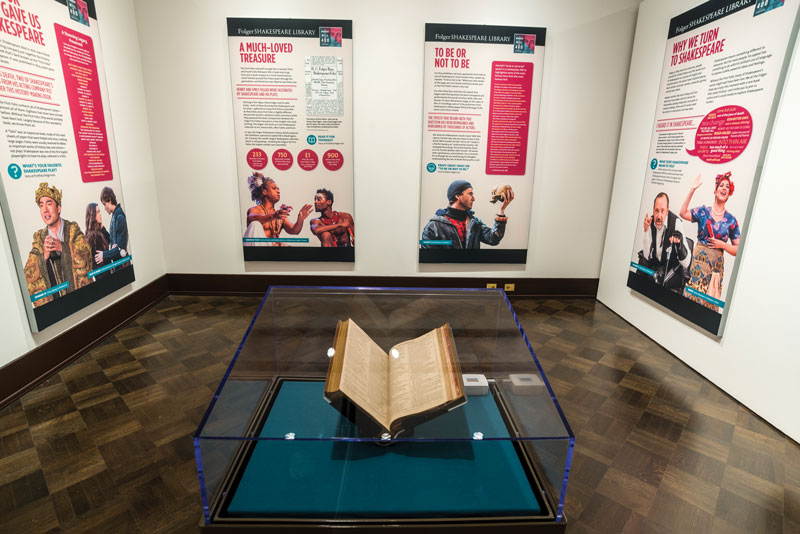

Throughout January, the First Folio was on display at the UO’s Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art. Complementing this exhibition, the university hosted a wide-ranging series of Shakespeare-related events on and off campus—from scholarly talks to guided tours of exhibits to the OSF performance that delved deep into the subtleties of how Shakespeare’s words are brought to life onstage.

At the heart of it all was a touring copy of the First Folio, housed in a protective case  and opened to the famous “to be or not to be” soliloquy in Hamlet (right). Thousands of visitors to the museum—schoolchildren, scholars, fans of literature and theater, from the merely curious to the truly enamored—streamed through to have a peek at the legendary text and learn more about Shakespeare’s singular legacy.

and opened to the famous “to be or not to be” soliloquy in Hamlet (right). Thousands of visitors to the museum—schoolchildren, scholars, fans of literature and theater, from the merely curious to the truly enamored—streamed through to have a peek at the legendary text and learn more about Shakespeare’s singular legacy.

(Meet the donors who made it all possible.)

The First Folio was not published during Shakespeare’s lifetime. Two of his fellow actors (and shareholders in his acting company) took it upon themselves to assemble a collection of his works in 1623, seven years after his death.

This was a radical act. A folio was an expensive book that signified prestige; it was usually reserved for Bibles and classical texts or important works of history, law and theology—not for “made up” imaginings, like scripts for plays.

At the time, dramatic works were considered morally suspect because they were seen to be “promulgating lies,” said Lara Bovilsky, associate professor of English.

Theater’s sketchy reputation was exacerbated by the actors themselves, whose performances defied class distinctions; on stage, they wore costumes representing the upper class and pretended to be kings and queens. Theater performances were further seen as dubious diversions because they distracted apprentices and servants from their work.

All in all, “theater’s marginal status as a place of idleness, crime and false representations—seen as sinful lies—meant that plays were deemed unsuitable for publication,” said Bovilsky. “They were considered unworthy.”

But this began to shift when playwright Ben Jonson dared to publish his own works in folio form (see “The Very First Folio”), provoking scorn for presuming to equate his imaginative scribblings with “loftier” forms of writing.

The Wonder of Will

Bovilsky shared her Renaissance-era expertise at two public talks that were part of the suite of UO-hosted First Folio events. But this was only a small part of her role in the extravaganza.

Bovilsky was the mastermind behind the successful Folger proposal. She not only wrote the proposal, but also wrangled the partnerships, emceed a gala performance, led guided tours for 400 people and curated two companion exhibits of materials from the UO Libraries Special Collections and University Archives that allowed visitors to learn more about the history of Shakespeare’s achievements.

“Lara’s leadership was exceptional,” said Jill Hartz, executive director of the museum. “Her knowledge of and passion for Shakespeare were contagious.”

The UO won out over other Oregon institutions as the host location because its proposal was driven by compelling and creative partnerships, and because the museum could meet the stringent security and climate requirements of the tour. Together, the on- and off-campus partners created dozens of opportunities for the wider community to participate—addressing the Folger Library’s desire to see a significant level of public engagement.

On the UO campus, the main collaborators were the museum, the UO Libraries Special Collections and University Archives, the Oregon Humanities Center and the Department of English. External partnerships included the Eugene Public Library, the City of Eugene’s Hult Center for the Performing Arts and, of course, the Oregon Shakespeare Festival.

“The swirl of events and the bustle of people orbiting the First Folio installation created a living, contemporary instance of Shakespeare’s magic,” said Ford.

Among the main attractions:

The Exhibition

To successfully compete for the privilege of hosting the First Folio, the UO had to guarantee the right kind of physical environment—and the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art was exactly the ticket. Thanks to the museum’s experience in exhibiting timeless treasures, the First Folio was front and center in a secure and spacious installation from early January to early February.

Attendance reached nearly 9,000, which included museum admissions, academic and K–12 tours and other public programs. Informational panels provided by the Folger Library surrounded the magnificent book, which was encased in glass and opened to the brooding ruminations of Hamlet.

A companion display of materials on loan from UO Libraries Special Collections demonstrated the depth of the holdings in the UO’s own library: a copy of Ben Jonson’s first folio; second and fourth editions of Shakespeare’s folio; and several engravings of Shakespeare-themed illustrations. Bovilsky curated these items and wrote the accompanying narrative that explained their significance.

“We are fortunate that, as a research university, we were able to contextualize the First Folio with related works from our university libraries,” said Hartz.

Time’s Pencil

This was a big reveal for UO Libraries Special Collections—an opportunity to showcase a wide range of Shakespeare-related gems preserved for posterity in its holdings. Special Collections loaned historic folio editions of Shakespeare’s and Ben Jonson’s works to the museum exhibition and opened its archives to Bovilsky, who curated a separate exhibition in the library called Time’s Pencil. (The title comes from a Shakespeare sonnet that dwells on the ways that time changes a person.)

This exhibition explored the influences that shaped Shakespeare as a schoolboy and budding writer, and how his works were understood, interpreted, rewritten, restored and performed over the centuries.

For instance, the first display case showed classics such as Ovid’s Metamorphoses that were central to Shakespeare’s early education. Another showed historic works from which Shakespeare freely “borrowed” (an accepted practice at the time); Plutarch’s The Life of Julius Caesar, for example, was a source that Shakespeare obviously mined for his own play about the ill-fated Roman leader.

Other display cases showed how—to suit the tastes of later audiences—some of Shakespeare’s tragedies were rewritten to end on happier notes (e.g., Cordelia marrying her beau at the end of Lear, rather than perishing with her father). Also on display: other creative riffs on Shakespeare, including illustrated children’s books based on his plays, revisionist recastings of secondary characters (e.g., Caliban from The Tempest portrayed as a Caribbean native subjected to colonial enslavement) and speculative fiction about Shakespeare’s love life (e.g., Oscar Wilde’s The Portrait of Mr. W. H.).

The accompanying narrative was again the work of Bovilsky. This exhibit ran for an additional month, through the end of March, and drew an estimated 1,000 visitors.

Sweetly Writ

Another compelling factor in the UO’s selection as the state’s First Folio site was the collaboration with the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. The renowned theater company, which draws visitors from all over the world to its home in southern Oregon, sent five actors, a director, a dramaturg and a stage manager to Eugene to produce Sweetly Writ, an inventive play-within-a-play created especially for the occasion. Its purpose was to demonstrate how Shakespeare’s works evolved (see “Side by Side: Quarto v. Folio”).

Performing to a packed house at the Hult Center (the performance space was donated by the City of Eugene), the actors assembled onstage and worked through a theme-setting portion of Act I, Scene I, in a line-by-line manner, weighing quarto versus folio language. The sections under discussion were displayed on a large screen for the benefit of the audience.

Once they had made their choices, the only costuming came out—a robe and crown for the king—and the actors performed the scene using the lines selected from the two versions. The actors and the dramaturg then took questions from the audience.

“It was an amazing event for people who love Shakespeare,” said Ford, who noted that the audience was so raptly attuned to the subtle nuances between quarto and folio that there were “hundreds of people gasping about semicolons.”

The performance was followed by a gala reception with Renaissance-era music and refreshments. Two Shakespeare-themed costumes, designed for a 2012 UO production, were flown back from an international exhibition in Moscow for the event (left).

The performance was followed by a gala reception with Renaissance-era music and refreshments. Two Shakespeare-themed costumes, designed for a 2012 UO production, were flown back from an international exhibition in Moscow for the event (left).

Other activities included a public lecture by English professor Ben Saunders, a performance of scenes from Shakespeare by UO theater arts students, a workshop for teachers and a screening of the film Shakespeare Behind Bars, with a public talk by the film’s director, Curt Tofteland.

“Shakespeare lived briefly, centuries ago, far from Eugene,” said Ford, reflecting on the entirety of these events. “But even now, centuries later, the First Folio has ignited our interest, excitement, curiosity, delight, discovery and creativity.”

—Lisa Raleigh

Photo credit: Shakespeare image (top) – Shakespeare First Folio, 1623, Folger Shakespeare Library; First Folio on Display – Jonathan B. Smith, JSMA

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Forward

Forward