Invisible No More

On a summer day in 2004, Julie Weise strode up to an aged stone building in Mexico City that housed the archives of the secretary of foreign relations for Mexico. She had a simple question: How long have Mexicans been in the Deep South—states like Georgia, the Carolinas, Louisiana?

Then a first-year doctoral student in history at Yale, Weise (read more about Weise here) was formulating a topic that could become her dissertation.

Fresh on her mind was the fact that California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger had recently repealed a measure that would have allowed undocumented immigrants to apply for driver’s licenses. Yet in the South, long toiling under a history of racial oppression, North Carolina and other states had been allowing such immigrants to obtain driver’s licenses for years.

“I said, ‘Wait a second—all this political Latino power and progressive policies (in California) and we can’t get this done, but there are these southern states that are doing it?’” Weise said. “That really intrigued me.”

With this apparent contradiction in mind, Weise set about a possible examination of the Mexican experience in the South.

In the foreign secretary’s archive, she could review records that showed how Mexican federal officials had been helping nationals migrating to the United States. How long, she wondered, had those nationals been going to the South?

Weise expected to find her answer in the 1970s. The Latino population in the South exploded from 1990 to 2000, with their numbers doubling to 4.9 million; the 1970s,

A snapshot from the Marin family album depicting their journey north from Florida in the 1970s.

Weise speculated, would have been a logical period for the arrival of the first Mexicans and the establishing of roots that would precede the bigger wave.

She began flipping through the card catalog, starting with the consulate’s office in New Orleans. “I looked under ‘N’ for ‘New Orleans’—‘were there any Mexicans there in the past?’” Weise said. “My question was as simple as that: ‘Were they there?’”

Were they ever. With seemingly every three-by-five-inch index card she flipped, Weise unearthed bits and pieces from the lives of a people who were adjusting to the ins and outs of a new country, as evidenced by the need for assistance from their home government: migrant protection complaints, farmworker issues, criminal cases, repatriation files—even questions about proper education for children and appropriate burial grounds for the dead.

In record after record, Weise found evidence of Mexicans living in Mississippi, Arkansas and other states across the South. Day after day, week after week, she pulled hundreds of documents and other records and snapped a photo of each with a digital camera. It was a treasure trove.

But for Weise, the true breakthrough was discovering when this migration began—the cases dated to the 1920s and 1930s. This flew in the face of everything that Weise knew—that any historian knew—about how long Mexicans had been in the South. Indeed, the Latino explosion in the 1990s was treated by journalists, scholars and others as if it had started from nothing.

It instantly dawned on Weise: The scope of her project would start not in the 1970s, but at the beginning—1910, the onset of the Mexican Revolution, which radically transformed one nation and forced untold numbers of its citizens to flee north.

“I definitely remember the day I pulled a little index card, ‘Mexicans buried in the black cemetery of Clarksdale, Mississippi,’ and it was in the 1920s,” Weise said. “And I just said to myself, ‘Whoa. No one has written about this.’”

HEART OF DIXIE

Now Weise herself has written about it. Corazón de Dixie: Mexicanos in the U.S. South since 1910, which took her 11 years and was published in 2015, is the first book to comprehensively document the history of Mexicans and Mexican Americans in the South, dating back to 1910.

The book recounts Mexicans’ migrations to New Orleans, Mississippi, Arkansas, Georgia and North Carolina. It follows them as they navigated the Jim Crow system, worked the cotton fields, appealed for help to the Mexican government and embraced their own version of suburban living in the twentieth century. The Organization of American Historians has awarded Weise the Merle Curti Award, calling Corazón de Dixie the year’s best book in American social history.

The book—Weise’s first—recognizes a people whose history has been neglected in official U.S. archives, not to mention classroom textbooks. Corazón de Dixie chronicles the contributions that Mexicans and Mexican Americans made to the South, their efforts to advance and their treatment at the hands of the region’s established groups—whites and blacks.

“The knowledge that there is a longer history around struggle for (Latino) rights is something that teachers and advocates want to communicate to young Latinos in the South so they feel less alien in that region,” said Weise, now an assistant professor of history at the UO. “It’s really hard to feel you don’t belong somewhere and you don’t have a history somewhere.”

The book has struck a chord, making Weise a hot ticket in the South—since the release of Corazón de Dixie last fall, she has been interviewed by public radio in North Carolina and Georgia, presented talks in Charleston and Charlotte and heard from advocates, educators and scholars who want to teach the book in schools and universities.

Erik Valera, a Latino community advocate in North Carolina, heard an interview with Weise on public radio and immediately reached out to her in an email.

Robert Canedo’s service in World War II was representative of a generation that embraced Americanism in the hope that the country would embrace Mexican Americans

One of the chapters in Corazón covers the 1942 bracero farm labor agreement that allowed millions of Mexican men to come to the United States on short-term labor contracts; Valera’s grandfather worked in the program and the book reminded Valera of his grandmother’s efforts to win compensation owed to the family.

“(The bracero program) is an important part of history that can’t be forgotten,” Valera said. “I told Julie, ‘These stories need to be put out, they need to be made accessible.’ In the same way I feel connected to the bracero program, Latino youths need to know they are not paving new ground, they are continuing a legacy.”

Robert Canedo (left) first acquired his US citizenship after World War II, but had enjoyed most of its benefits for decades—benefits not enjoyed by those New Orleans citizens who were African American. Though his skin was dark and his mother was a poor widow raising a family on the proceeds of her sister’s boarding house, in 1930 young Robert attended kindergarten with white children. . . .

By the time he enlisted in the army, Canedo had already fallen in love with his future wife, a U.S.-born white woman named Hazel. —Corazón de Dixie

WORKING THE PHONE BOOK

Part of what gives Corazón de Dixie resonance is that Weise has populated it with intimate snippets from individual lives. The book is more than a cold recitation of the facts of Mexicans’ long-standing presence in the South; through Mexican and U.S. records research, interviews and family photographs, Weise paints vivid portraits of the lives of the first Mexicans in the region, detailing their expectations, strategies and dreams.

Much of the book is based on interviews that Weise conducted

A 1928 photograph of Rafael Landrove and his family represented the U.S. ideal of middle-class stability. But for the Landroves, economic progress was more an aspiration than a reality.

with descendants of those first Mexican families. Finding them was basic, shoe-leather detective work: Armed with lists of names procured from the genealogy website ancestry.com, Weise worked the phone book.

“You call and say, ‘Hello, I’m a historian doing research on Mexican immigration to New Orleans, are you a descendant of Francisco Cervantes, who lived in New Orleans in the ’20s and ’30s?’” Weise said. “Either they hang up on you or they say ‘no’ or they say ‘yes.’ I wanted anything they knew—anything they had that I could scan, anything to bring more understanding of what these people’s lives had been like.”

Though his brother Constancio had found a measure of economic stability in San Antonio, Rafael Landrove’s (right) failure to do so parallels the declining fortunes of most Mexicans in South Texas during the 1920s. . . .

By 1924, Landrove was traveling to work in the rapidly expanding cotton industry of East Central Texas, and there he wed Martha Perry (or possibly Pérez), a Tejana from the East Texas town of Nacogdoches. Within three years, the couple had moved yet again, to Lake Cormorant at the far northern end of the Mississippi Delta.

—Corazón de Dixie

B.B. KING COUNTRY

Many of the people Weise contacted were only too happy to do what they could to help her reclaim a history largely overlooked.

She developed the story of Rafael Landrove, for example, while she was doing research in a Mississippi Delta library. A Mexican American man with a passion for history had taped interviews with his grandparents and contributed them to the repository.

Once contacted by Weise, this man—a Mississippian and member of the area’s Enriquez family—provided a photo of Landrove, who had been a friend of his own ancestors.

The man also took two days off from work to drive Weise through the Delta region and describe his family’s life in Mississippi (out of respect for the man’s privacy, Weise declined to provide his full name). The two traveled rural roads to tiny, economically depressed towns—“B. B. King country,” Weise called it, and quoting another historian, added, “‘the most Southern place on Earth.’”

Behind closed doors, Weise found, many of those families had maintained a strong Mexican cultural life even while hiding it from the outside world so that they might join white society. The man’s grandmother showed Weise the place in the house where the family once hosted the Mexican bands from Texas that inspired dancing in every room.

“It seemed important to him to figure out how to grapple with this history somehow,” Weise said. “I think he understood why others wanted to run away from it. But I think he was also in pain about that because he felt connected to that history and he hated the fact that friends and relatives were running from it.”

Claude Kennedy, an African American man, recalled how Mexicans’ superior access to public space only stoked his indignation at the Jim Crow system. “They could go to the movies with whites, where black people still had to go upstairs,” Kennedy said. “That was something that black people could not understand.” He remembered his mother, a schoolteacher, explaining to him why Mexicans were not subject to the painful discrimination of Jim Crow. “Their government would not allow them to be treated that way,” he recalled. —Corazón de Dixie

BONDING AT THE BARBER SHOP

Weise’s attempt to paint a richer portrait of the Mexican experience in the South was not of importance to Mexicans and Mexican Americans alone—African Americans also had memories to share on the history of Mexican immigration. Weise gleaned rich anecdotes from interviews with people such as Claude Kennedy, of the Arkansas Delta.

As Mexicans moved into the South, Mexican officials repeatedly intervened on their behalf to try to address clashes over discrimination, farmworker compensation, education and other rights. For Kennedy, it was a bitter experience, indeed, to compare Mexico’s support of its citizens abroad with his own government’s enforcement of racial segregation.

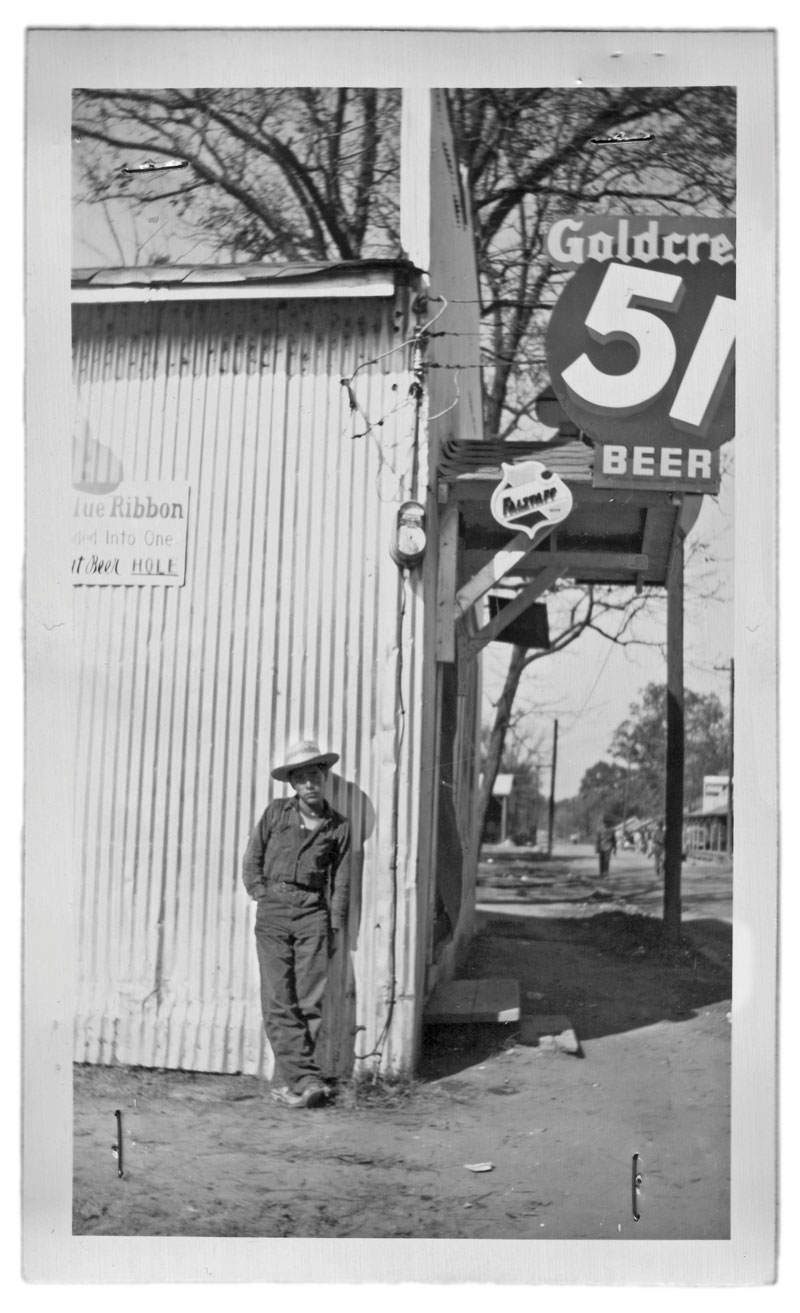

an image from 1949 of a Mexican man who picked cotton in Arkansas

He held nothing against the immigrants, though. Kennedy, in fact, related an experience to Weise that illustrated his empathy: He was about to get his hair cut one day at a black barber shop when a Mexican man walked in; the man spoke no English but was able to communicate that he had been a barber in Mexico—he hoped just to cut someone’s hair, no money involved. Kennedy agreed.

“I asked Mr. Kennedy, ‘How did he do?’ and he said, ‘Well, he made it a bit longer than I would have liked,’” Weise said. “But it was a very interesting moment, with this black man saying to this Mexican man, ‘I know what it’s like to be treated like you

are so much less than you are, so I’ll give you this opportunity to recover that part of yourself.’”

Maggie Mackenzie was a Mississippi-born white woman alone in her thirties with six children to support. She married Frank Torres, a Texas-born Mexican American man nine years her junior. While marrying a black man in the 1920s would have brought banishment or even death to an impoverished white woman in the Delta, marrying a Mexican American man apparently was more acceptable. Having grown up in Texas, Frank Torres knew well the benefits of marrying “up” in the racial hierarchy, which may have motivated him to do so despite Maggie’s more advanced age and the financial burden of supporting her six children. —Corazón de Dixie

“GRANDDAD’S FROM TEXAS”

Weise’s calls were not always welcome.

Many of the first Mexican families, especially those in Mississippi, moved up in the world by assimilating—they married white people and sent their children to white schools, once they had won the right to do so. They deliberately avoided public discussions of their ethnic heritage, Weise wrote in Corazón, which was “the cost for their admission to the Mississippi Delta’s white middle class.”

That reluctance to reveal “the family secret” endures.

“They just didn’t want to talk about it,” Weise said, recalling some people’s reactions to her. “They’d have darker skin and Hispanic surnames, but they’ll say, ‘Granddad’s from Texas,’ and that’s the end of that.”

The move by Mexicans in the South to join white society or move quickly to another region effectively “erased” their historical footprints. But there are other reasons their history went unnoticed for so long.

Historians usually start their work with government archives. But local, state and federal officials in the U.S. had relatively little interaction with the emerging Mexican community prior to the bracero farm labor agreement in 1942.

There were, in fact, plenty of secondary records—newspaper stories, school records, police reports, baptism registrations, the papers and photographs that families passed down from one generation to the next. But nobody asked the question, Weise said—including historians.

“We thought of this region as ‘black and white,’” she said. “It didn’t fit into our ideas about what the South is and where Latino history takes place.”

NEEDLE IN A HAYSTACK

The building in Mexico City that housed the foreign relations archive when Weise began her research was a stately former convent with vaulted ceilings and sunlit windows. Weise felt her spirits lift every morning as she walked across an open courtyard and through the convent’s massive wooden doors to begin her work.

Her investigation was pure needle-in-a-haystack: She planned to sift through piles of records from both countries—first in Mexico, then in the U.S.—in the hope of finding at least a few that might give some sort of clue as to when Mexicans began arriving in the South.

Fortune was on her side. Weise chose to start in Mexico, and that made all the difference.

As a graduate student with no experience as a historian, Weise was reluctant to start her research in the U.S., which would have required learning to navigate the National Archives and Records Administration, a sprawling Washington, D.C.–based agency with more than 10 billion records.

But Weise had worked for two years in Mexican President Vicente Fox’s administration as a speechwriter and researcher. She understood how that federal bureaucracy worked, and she felt comfortable in it.

Weise knew, for example, that Mexico had stationed a consul in New Orleans since the nineteenth century to facilitate maritime trade between the two nations.

Thus, by searching the foreign secretary’s records under “New Orleans,” Weise quickly learned of scores of cases involving Mexicans in that city and across the South. That meant that Weise, upon returning to the U.S., would know which cities to review for records, and also what types of documents there might be. By starting in Mexico, in essence, she learned where to look later, in a haystack of U.S. documents, for the “needles” that would help her answer her question.

Had Weise started her research in the states, the job would have been almost impossible because there were no overarching government files on this emerging community. There were only secondary records—school attendance reports or newspaper clippings, for example—in which Mexicans and Mexican Americans were mentioned in passing. She wouldn’t have known where to look or what to look for.

“Archives on the U.S. side were not organized in such a way (for the South),” Weise said. “There was no ‘M’ for Mexican.”

“This is a real person”

Weise’s book is distinguished by her ample use of vintage photographs provided by friends and descendants of the first Mexican families in the South.

“I feel like you have to work with what you’ve got when you work with people who aren’t the main subjects of archival collections,” Weise said. For Mexicans in the U.S. South, often that meant a family photograph.

An examination of one such photograph exemplifies how a historian can use a resource such as the genealogy website ancestry.com to breathe life into a snapshot from the past.

In Corazón de Dixie, Weise includes an image of Rafael Landrove provided by Enriquez, the Mississippian who had taken her to visit his grandmother. The photograph, a posed portrait from 1928, shows Landrove, his wife, Martha, and their baby.

For a fee, Weise was able to pull information from ancestry.com about the family, their professions, their neighbors and even their movements from state to state. With that in hand, Weise takes readers “into” the photograph, to the underlying story: a family attempting to recreate the middle-class ideal of an economically independent husband, a nonworking domestic wife and a baby who will inherit the wealth and privilege bestowed by her parents.

Martha is photographed in a fur coat and pearl necklace, for example—but Weise knew from the records that those items only suggested a wealth that the couple did not actually possess. They are shown sitting on a bench, but it was one that didn’t fit in with their sharecroppers’ cabins in the northern Mississippi Delta, Weise wrote.

The image exaggerates the qualities of economic progress and privilege, Weise concluded, “depicting an aspiration more than a reality.”

She even used the website to confirm that the photograph is, in fact, Landrove. Because ancestry.com includes naturalization records, Weise was able to review a category in those records for “distinctive marks”—for Landrove, the record listed that a finger was “foreshortened.” In the photograph, part of the first finger on his right hand appears to be missing.

For Weise, there was deep satisfaction in using the photograph to put a human face on a people who had long been nearly invisible to history.

“With him, that was just a moment of, ‘this is a real person,’” Weise said. “These were people.”

Fantasy becomes reality

The initial response to Corazón de Dixie has exceeded Weise’s expectations.

There are the media interviews and speaking engagements. Weise’s peers keep sending pictures of classrooms at universities where they are now teaching the book—the University of Alabama, the University of Texas at San Antonio.

Nor is the book’s popularity bound by academia. A museum and an economic think tank in North Carolina have both been in touch about ways to publicize the histories that Weise tells in Corazón de Dixie.

After giving 11 years of her life to this effort, Weise acknowledges that there came a moment, as she was correcting footnotes, that she “nurtured the fantasy” that Corazón de Dixie would become something more than just a research book collecting dust on a shelf.

“It’s just been so wonderfully rewarding to see that people care,” Weise said. “And since the book just came out, I hope this reaction is only just beginning.”

—Matt Cooper

Images courtesy of Julie Weise, Corazon de Dixie

Top image caption: Mexican and black cotton pickers inside a plantation store in the Mississippi Delta in 1939

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Forward

Forward