Social Sciences

Social Sciences

Elder Wisdom

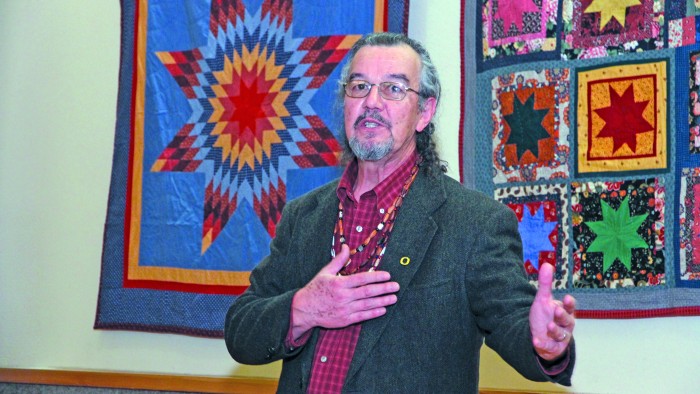

Don Ivy would be the first to say that being a tribal elder doesn’t mean he’s got all the answers.

During a visit to campus earlier this year, Ivy (pictured) shared with an environmental studies class a story about a wetlands restoration project that he and his Coquille tribe helped coordinate—which went awry. In an effort to reclaim 400 acres of rich salt marshes along the Coquille River on the southern Oregon coast, conservationists unwittingly created the perfect conditions for the reproductive cycle of . . . mosquitoes.

The class released a sympathetic sigh, acknowledging the complex interplay of factors when pursuing environmental remedies. “But if you want to have healthy rivers and healthy wetlands,” student Kathryn Alexander asked, “aren’t you going to have mosquitoes?”

“It’s not a question of whether we can learn to live with mosquitoes—of course we can,” Ivy responded. “But when our actions as humans are set in play without our complete understanding of a situation, there can be unintended consequences.”

It was one of many pearls of tribal wisdom that Ivy delivered during an inaugural program designed to improve the understanding and knowledge of Native American traditions among the UO community.

The Traditional Scholars Program, an initiative of the Office of Equity and Inclusion, will annually bring to campus elders from Oregon’s nine federally recognized tribes, as well as representatives from other communities. Described by the office as “transmitters of knowledge and wisdom,” these special guests meet with the president and other leaders, lecture in classes and provide public addresses to students, faculty and staff members and the public.

Ivy recently retired as cultural resources program coordinator and tribal historic preservation officer for the Coquille, who have traditionally lived on the southern Oregon coast. In addition to two public addresses on native and nonnative law, he met with various groups, including instructor Peg Boulay’s aforementioned environmental studies class and an Introduction to Native American Studies class with Brian Klopotek, an associate professor in ethnic studies.

A plainspoken sort who—rather than lecture—endeavored to engage students in conversation, Ivy said in an interview that he could feel an “angst” around campus regarding the sensitive topics of race and diversity. Ivy has endured his own struggles with race and identity—his birth doctor marked him as “White,” he said, in an effort to make Ivy’s life easier—and he urged the university community to focus on what is held in common, rather than emphasize differences.

Oral traditions, Ivy noted by way of example, are not the domain solely of native peoples; everyone has an oral tradition that addresses family and origins.

“When we get into this discussion of ‘native’ or ‘tribal elder,’ there’s a heckuva lot going on there,” Ivy said. “Let’s talk about being human, first. And then let’s examine native people as one constituency that have some unique qualities and perspectives relevant to the human experience.”

Yvette Alex-Assensoh, vice president for equity and inclusion, said she was delighted by the enthusiastic response to Ivy’s visit.

“This is a campuswide opportunity to recognize and celebrate the presence of native communities and students on our campus,” she said. “It will also support our efforts in retaining and recruiting native students.”

— Matt Cooper

Caption: Don Ivy’s visit to campus included a speaking engagement at the Many Nations Longhouse, where students and the community also recognized him with a blanketing ceremony, traditionally held in honor of those of high importance. Also in attendance were university President Michael Gottfredson, members of the Native American Student Union, faculty members and staff. Photo by Jack Liu.

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Forward

Forward