Humanities

Humanities

Depathologizing disability

The musical genre “krip hop” features disabled artists who share their view of the world through rap. This is one of several innovative forms of narrative that interest Betsy Wheeler, an associate professor of English.

Wheeler researches how disabled children and teens are portrayed in literature and new media, from toddler’s picture books to graphic novels, music videos and poetry slams.

She also has a deep personal interest in this subject because she is the parent of a thirteen-year-old son with cerebral palsy and has also experienced a disabling migraine condition.

Wheeler’s forthcoming book, “HandiLand: Kids with Disabilities in Literature and New Media,” explores how literary depictions of disabled youth have evolved in recent decades, and how youth are increasingly taking center stage in these narratives.

With krip hop, the artists themselves embrace the usually disparaging term krip (short for crippled; krip hop founder Leroy Moore, a rap artist with cerebral palsy, changed the spelling to avoid association with the Crips gang). These rappers share their personal encounters with discrimination and harassment and their aspirations for acceptance for who they are.

For centuries, disabled persons served mainly as thematic devices in literature, says Wheeler. Tiny Tim, for instance, in Dickens’s “A Christmas Carol,” isn’t really developed as a character, she said, but instead “serves as a reflection of the moral character of the main character,” Ebenezer Scrooge.

In addition to literature, an entire subgenre of nonfiction works about disabled children has been authored by experts such as doctors, psychologists and parents. But who is most expert about the experience of a disabled person?

Wheeler has asked herself this very question about her own son. While she makes decisions on his behalf as a parent and has gained special knowledge as a mother raising a disabled child, “there are some things my son can learn only from someone who has cerebral palsy,” she said. Thus the importance of narratives that directly depict the point of view of someone with a similar experience.

In recent decades, disabled teens and children increasingly have moved from the margins of stories into central roles in picture books for children, chapter books for teens and young-adult novels, says Wheeler. This trend builds on the advent of special education in schools in the 1970s and the Americans with Disabilities Act in the 1990s.

“This shift puts the person with the disability at the center of the narrative,” she said.

This serves disabled children, who now have main characters to identify with, and other children, who gain examples that help them better understand and value individuals with different abilities. The result is to depathologize disability, said Wheeler.

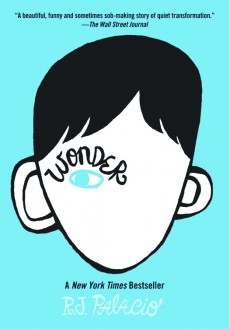

Examples of popular children’s books include “Wonder,” a New York Times bestseller about a boy with a facial deformity who finally gets to enroll in a mainstream school; the Moses series (“Moses Goes to a Concert,” “Moses Goes to the Circus”) about the adventures of a deaf boy and his friends; and “Seal Surfer,” about a disabled boy’s special bond with a seal.

All these books are written by adults, but disabled youth are increasingly narrating their own stories, and this is where new media comes in. On YouTube, you can now find American Sign Language poetry slams featuring deaf artists and krip hop performances.

These first-person accounts challenge the assumption that disabled persons must strive to pass as “normal” — that is, to train themselves to speak and move in a way that others define as normal.

This strikes both a personal and professional chord for Wheeler.

“I have learned to resist attempts to normalize my son,” she said. Instead of urging him to be someone he can’t be, “I want to mirror my son back to himself.” And that’s exactly what literature can do, too.

— Lisa Raleigh

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Forward

Forward