The seeds of Jon Erlandson's big theory were first planted in his childhood, while diving, swimming and sailing off the coasts of California and Hawaii.

Now a UO anthropologist who directs the Museum of Natural and Cultural History, he says that connection to the sea led him to question one of his field's common assumptions: That, until fairly recently, humanity was a race of incorrigible landlubbers.

"It just didn't sound right to me," Erlandson said. "The coast offers the resources of the sea and also the resources of the land. Some of these peoples had large populations with complex cultures. How could they support all those people without using the abundance of the sea?"

Erlandson's research, recently highlighted in Science and the New York Times, has found evidence of early hunter-gatherers taking to the sea and harvesting its bounty earlier than once believed. Conventional wisdom suggested that true fishing societies didn't exist until 6,000 to 8,000 years ago, around the time of the spread of agriculture.

Erlandson's research, recently highlighted in Science and the New York Times, has found evidence of early hunter-gatherers taking to the sea and harvesting its bounty earlier than once believed. Conventional wisdom suggested that true fishing societies didn't exist until 6,000 to 8,000 years ago, around the time of the spread of agriculture.

On California's Channel Islands, Erlandson has found evidence that pushes that date back to at least 12,000 years ago, though he believes the sea has been in our blood for far longer.

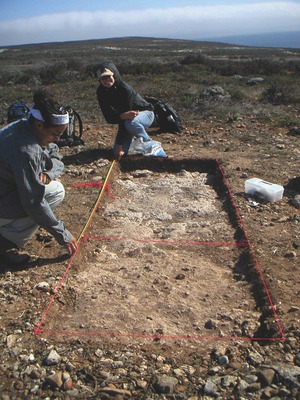

UO students Tracy Garcia and Casey Billings map a test trench at a 11,600-year-old shell midden on San Miguel Island.

Recent research has identified 160,000- year-old shell middens in South Africa, according to Erlandson, and "the colonization of Australia happened at least 50,000 years ago, requiring sea crossings of nearly 100 kilometers. You don't head out to sea toward a bare horizon without a sense of adventure and faith that land is out there."

With his former student, Torben Rick (now at the Smithsonian Institution), Erlandson used Channel Island shell middens to meticulously reconstruct fossil records that show the impact of early peoples on the coastal environments.

Middens are ancient piles of discarded shells, bones and other detritus that provide hints as to what resources were being extracted thousands of years ago. And because most of the world's middens are less than 6,000 years old, it was thought that was the timeframe during which seafaring cultures first developed. But Erlandson argues that older evidence is often submerged beneath the ocean due to melting glaciers, rising seas and shifting coastlines.

Not only does his work rewrite the history of human subsistence, but it could also prove vital in modern efforts to restore marine ecosystems in oceans that have suffered from massive overfishing. With a better understanding of when humans first started impacting the oceans, scientists can improve their estimates of what fish populations looked like in pristine waters.

"It means we can't just go back 100 years to understand how abundant salmon or whales were. We might have to go back 10,000 years," Erlandson said. Though his work shows that hunter-gatherers, often imagined to have lived in harmony with nature, were disrupting ecosystems, Erlandson says modern humans can learn many lessons from them about sustainability.

"They were restricted to near-shore fishing, so they weren't ravaging the open oceans like we have in the last 200 years," he said. "They rarely drove species to extinction. They adjusted their diets and habits to sustain themselves. For the sake of our oceans, hopefully we can do the same."

- Mark Dadigan

Photo courtesy Jon Erlandson

When the volcano erupted, a UO professor discovered that local residents consoled themselves through song.

When the volcano erupted, a UO professor discovered that local residents consoled themselves through song.

Join UO neuroscientists as they bring the host of the PBS series, The Human Spark into their brain research lab.

Join UO neuroscientists as they bring the host of the PBS series, The Human Spark into their brain research lab.  Temple Grandin, perhaps the world's best known person with autism, drew an overflow crowd to her UO talk.

Temple Grandin, perhaps the world's best known person with autism, drew an overflow crowd to her UO talk.

Watch a slideshow about Elena Rodina's journalistic globetrotting, from the Arctic Circle to Cuba.

Watch a slideshow about Elena Rodina's journalistic globetrotting, from the Arctic Circle to Cuba.