Humanities

Humanities

A Language Within A Language

In 1906, anthropologist Edward Sapir—a pioneer in the development of linguistics—met with a Native American woman in southwest Oregon named Frances Johnson, who was the last fluent speaker of an indigenous language called Takelma.

Over a series of interviews that summer, Sapir developed what would become the largest body of material available on the language by making audio recordings as Johnson provided personal narratives, medicine formulas, elicitations, and Takelma mythology. With Johnson’s death in 1934, Takelma fell silent.

Until now. Johnson’s descendants have begun to restore a language that has not been spoken in more than 80 years. Their efforts will rely in part on the work of Stephanie Evers (above), a 2015 UO linguistics graduate whose research on the topic can best be described as exacting.

“I loved working with this language,” Evers said. “It was a new challenge, a new puzzle every day. I found it intellectually rewarding and it was also extremely meaningful to me personally.”

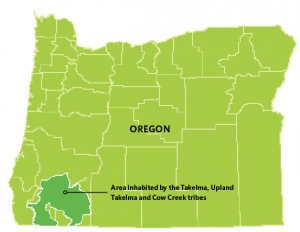

The Takelma were a Native American people who originally lived in the Rogue Valley, with most of their villages sited along the Rogue River; “Takelma” means “(Those) Along the River.” Their land was agriculturally rich and highly valued by settlers, leading to the Rogue River Wars and forced relocation of the Takelma in 1856.

In its effort to restore the language of their descendants, the Cow Creek Band of the Umpqua Indian tribe has partnered with the UO’s Northwest Indian Language Institute (NILI). The institute provides native language teachers and community members with training in linguistics, language teaching, and development of materials and curriculum. Students in the linguistics department have also worked on a revitalization of Takelma; that opened an opportunity for Evers, who was seeking a subject for her senior thesis, to tackle a six-month research project.

It’s been a humbling experience, says Evers, and not just because her work is a link in the chain that connects the Cow Creek to their ancestors. She was challenged by the fact that she had to rely on dated and hard-to-use source material to prepare her analysis of a long-dormant and complicated tongue.

In an effort to provide future teachers of the language with course material, Evers documented verb structure: verb stems, tense, and the order of subjects, objects, and actions in a sentence. Takelma often, but not always, employs a subject-object-verb order, so that the idea “coyote threw frog into the water” would be spoken in the order, coyote-frog-water-throw.

Evers first had to interpret a language within a language—Sapir’s records. The anthropologist-linguist published his work on Takelma in the early 1900s, well before the standardization of modern linguistic conventions that would have made it easier for Evers to find patterns in usage.

“It was a lot of work just trying to understand what he was saying,” Evers said. “I had to figure out how things he identified in the language correspond to what I’m seeing now, which is very tricky.”

One Word, a Complete Sentence

Even more challenging was the task of translating Takelma itself. Verbs in the language can be lengthy compounds constructed from smaller parts, capable of expressing a complete sentence’s worth of ideas in a single word. For example, the verb “teekwàlt’kwiip’anp” translates to “take care of yourselves.”

Evers noted every utterance of a particular verb and the context in which it was used, developing a spreadsheet that quickly comprised nearly 1,500 verbs.

“This kind of analysis is very painstaking,” Evers said. “It requires a lot of attention to detail. That’s always challenging.”

Evers’ work was possible only because of the linguistics department’s focus on lesser-known languages and empirical research in syntax, semantics, and phonology (the organization of sounds in a language).

Some linguistics majors at the UO study second-language acquisition, Slavic linguistics, or the relationship between language and society. But all of them take grammar, which introduces them to language morphology and syntax, both necessary for breaking words down and understanding how they come together in a language, Evers said.

In classes on syntax, she did weekly assignments in which she analyzed samples from languages around the world, looking for consistencies across cultures. Meanwhile, her studies on morphology gave her a foundation with “morphemes,” which are the smallest grammatical units in a language. “Dogs,” for example, is composed of the morpheme “dog,” which indicates the canine species, and the morpheme “s,” which means plural, of course.

Nuances and Building Blocks

Her command of morphemes was put to the test in documenting a language where the order of subjects, objects, and verbs is extremely fluid and verbs themselves can stand alone as a complete sentence. For her research, Evers put aside some of Takelma’s more complicated nuances and instead zeroed in on “building blocks” such as the order of morphemes in a simple verb.

During her project, Evers (right) leaned heavily on department head Scott DeLancey and Joana Jansen, a research associate at NILI, for resources, guidance, and feedback. “There’s absolutely no way that I could have done this without them,” Evers said. “They were both immensely supportive.”

During her project, Evers (right) leaned heavily on department head Scott DeLancey and Joana Jansen, a research associate at NILI, for resources, guidance, and feedback. “There’s absolutely no way that I could have done this without them,” Evers said. “They were both immensely supportive.”

Evers was inspired to study indigenous language preservation while taking a course in linguistics policy and planning from Janne Underriner, who is also director of NILI. Underriner put Evers to work at NILI, where the student applied her growing knowledge of grammatical analysis to better understand Takelma.

“She saw it as an academic challenge,” Underriner said, “and an opportunity to make accessible this language data that had otherwise been unreachable to tribal community members.”

Underriner called Evers’ work “unique for an undergraduate student,” and now Evers is taking it to the next level: she has been accepted to a doctoral program in linguistics at the State University of New York at Buffalo. Her first exposure to an independent research project was so satisfying that she can’t wait to start another.

“Whatever I do with my life, I need it to be two things,” Evers said. “I need it to be a challenging problem that I get to solve, and I need it to be something that tangibly benefits society. That’s what it’s all about to me.”

—By Matt Cooper

—Map credit: Atlas of Oregon, 2nd Edition, 2001

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Forward

Forward