Natural Sciences

Natural Sciences

Undergraduate Symposium

It’s one thing to commit the countless hours of work necessary to complete a research project. It’s quite another to present that work to the world.

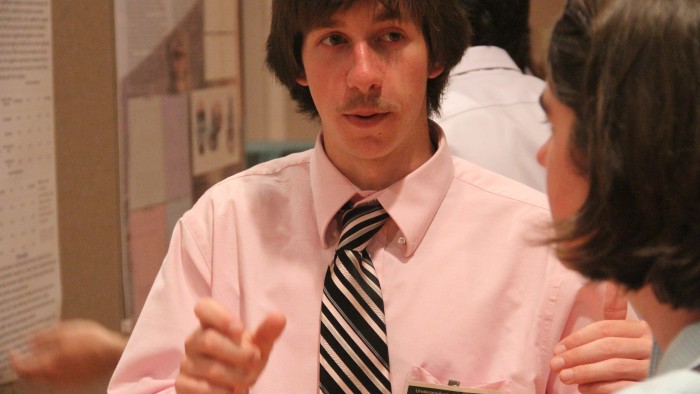

Mathew Beattie (above) experienced this firsthand at the 2014 Undergraduate Symposium, a research showcase for undergraduates at the University of Oregon. Majoring in both biology and geology, the junior came to the symposium last May to share his research on how diet affects development in mammals, eager to engage in conversation about his work. A parade of visitors who stopped by to view his poster at the event was more than happy to oblige:

“Why did you do it this way?”

“What if you’d done this test?”

“Did you consider looking at this?”

Beattie didn’t shy away from this critical analysis of his project. In fact, he welcomed it.

“The symposium provides a platform to get your ideas out into the community,” he said. “I’ve never been the kind of person who needs to be right. I want the right answer; if you have the ability to help me find the answer, then I’m all about a critique. I’m never going to dissuade discussion.”

Talk about research

A multidimensional conversation about research: That’s one way to look at the annual symposium, a daylong event during which young scholars interact with peers and faculty members and practice presenting their work to a group that could one day be pivotal for their success—the general public.

(Check out these “Fun Facts” from the 2014 Undergraduate Symposium.)

More than 100 students participated in the fourth annual campuswide event, which features work in the natural and social sciences, humanities, the arts, design, architecture and business. Consistent with the university’s status as a leading public-research institution, the symposium provides a training ground for students as they start developing the presentation skills they’ll need to be successful in careers, said Kevin Hatfield, an event organizer and assistant director of residence life.

“If part of what we’re doing is walking students through the scholarly process, this is helping students take the next step: ‘What do I do after the research is complete?’” Hatfield said. “For some students, it’s the first time they’ve presented their research in public. They’re learning transferable skills—how to talk to a lay audience—that propel them to graduate school and professional careers.”

Sharpening style and clarity

Symposium entries must represent “original undergraduate research,” Hatfield said—the creation of new knowledge. But there are multiple ways to meet the requirement. Students can submit their work toward a senior thesis, contribute to a laboratory project, complete an extensive, term-long assignment or even create an artistic effort, which falls in the symposium’s creative-performing arts category.

All submissions must be approved by a faculty mentor. A faculty panel then reviews each submission, working with the applicant to sharpen the style and clarity of the project over a period of weeks; this is a “blind review process,” Hatfield noted, in which the panel does not know the applicant’s identity.

Those accepted to the symposium choose from two formats for presenting their work: poster-sized displays of their research or oral panel discussions, during which students give brief, formal lectures to an audience and then answer questions.

There’s more to research than sequestering yourself in a lab or toiling endlessly over spreadsheets, Hatfield said—scientists and scholars must be able to explain their work in ways that inform and inspire a variety of audiences, from peers, academics and employers to prospective donors and the general public.

Poster presenters learn to summarize and illustrate complex ideas, using images and other visual aids to design compelling, easy-to-follow displays. In the spontaneous interaction with those stopping by to view their posters, they learn to translate complicated concepts into conversational language. The oral panelists, meanwhile, practice responding to technical questions like those they’ll be receiving at academic conferences and in informal and formal settings at the graduate and doctoral level.

Both formats “help you become a better researcher,” Hatfield said. He recalled the words of Daniel Wildcat, a professor at Haskell Indian Nations University, who was a keynote speaker at the 2012 event: “You need to be able to explain your research in a way that your grandmother can understand what you’re working on.”

Supporting the symposium

The university supports symposium participants in multiple ways. Faculty mentors help applicants with the research itself, including how to frame and pursue key questions; the symposium also provides workshops on how to design a poster, write a research abstract and speak to a crowd. All student expenses are covered, including poster materials and handouts.

Lisa Freinkel, vice provost for undergraduate studies, said the UO is committed to fostering the process of discovery for students and the breakthroughs that undergraduates make in scholarship, creativity and innovation.

The breakthrough for Amanda Hammons came during her poster presentation at the symposium.

Hammons, who received her degree in psychology and German just a few weeks after the symposium, has been accepted to a master’s program in Ontario, Canada. She chose the poster-presentation method to share her work on children’s speech errors because she wanted to start thinking about her work in a new way—that is, how to translate reams of information into a few eye-catching illustrations and charts.

With visitors stopping by her poster every few minutes, Hammons also got practice—again and again—in boiling her research down to the essentials.

“That was really great—not everyone that stops by wants to hear this twenty-minute talk about what you did,” she said. “It forced me to come up with an ‘elevator speech,’ which made me think critically about the most important parts of my project.”

Junior Marina Gross (right), on the other hand, wanted to go deep with her research: She chose the oral panel so she could make a more expansive case for her work in accessing long-term memory.

She chose the oral panel so she could make a more expansive case for her work in accessing long-term memory.

Gross plans to become a professor of cognitive psychology. At the symposium, she said, she practiced how to make her work accessible to a diverse audience that included experienced researchers, faculty members from various departments and students in other majors. She also brushed up on her public-speaking skills.

“The symposium gave me a chance to calm my nerves during a presentation,” she said. “It can be a nerve-racking experience, but with practice, my voice gets calmer and I get to enjoy myself more and more while standing in front of a larger crowd.”

—Matt Cooper

Photos: Matt Cooper

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Forward

Forward