School of Thought

The Araboolies have come to town and turned it upside down.

That’s the main arc of the story that fourth-grade teacher Ben Dechter (below) was reading to his class at Camas Ridge Elementary one day last February. He donned a microphone headset and held aloft a colorful book, strolling among his students and reading aloud The Araboolies of Liberty Street.

Dechter was preparing his class for its weekly philosophy discussion, to be facilitated by two UO students.

In The Araboolies of Liberty Street, all the houses on Liberty Street are painted white and look exactly alike. The neighborhood rules are enforced by General Pinch, who doesn’t like noisy, game-playing children and routinely threatens to “call in the army” for infractions of the rules.

In The Araboolies of Liberty Street, all the houses on Liberty Street are painted white and look exactly alike. The neighborhood rules are enforced by General Pinch, who doesn’t like noisy, game-playing children and routinely threatens to “call in the army” for infractions of the rules.

Then the fun-loving Araboolies arrive. They drive a Ken Kesey-like bus—painted wildly and bursting with outrageous characters: the Araboolies themselves, a multigenerational clan whose skin tones range from purple to green to canary yellow, and their menagerie of fanciful pets. They do not speak English. They do not conform to the rules. They paint their house with red zigzags and sleep together on a giant bed on their lawn. The neighborhood kids love them.

The General is not a fan. He actually does call in the army, directing the troops to remove the house that is “different.” But overnight, the neighborhood kids paint all the houses—except the General’s—with crazy patterns and colors. So the army naturally targets the house that now looks different: the General’s.

This sets the stage for several thought-provoking questions: What is normal? What is weird? How can you tell? Who decides what the rules are?

This sets the stage for several thought-provoking questions: What is normal? What is weird? How can you tell? Who decides what the rules are?

Dechter finished the story and welcomed into the circle UO senior Cassie Lahmann and sophomore Chris Wilson (pictured at top), who would be leading the discussion, just as they had done each Wednesday all winter term.

The Skill of Thinking

Lahmann and Wilson were enrolled in Philosophy 399, Teaching Children Philosophy. This innovative learn-by-doing course—a collaboration between the Department of Philosophy and the College of Education—prepares UO undergraduates to go out into local elementary schools to facilitate philosophical discussions relevant to children.

“All of our questions are designed to help the children clarify their beliefs,” said Paul Bodin, a UO instructor who designed and teaches the class. “We are trying to help children frame a personal thought related to experience. It’s all about the skill of thinking.”

The course gives UO students direct classroom teaching experience and trains them to assist children in “framing coherent points of view, revising opinions based on new evidence and applying elements of logical thinking to a wide range of questions,” according to the syllabus. These questions range from “What is friendship?” to “Do animals have rights?” to “What does it mean to be brave?”

“By the end of the term, undergraduates have learned how to engage and excite young people when they enter into meaningful dialogue with each other,” said Bodin.

Bodin, who taught elementary and middle school for twenty-five years in the Eugene 4J district, provides “discussion templates” that create a general framework for leading the fourth-grade and fifth-grade classes—but the actual outcomes can be “incredibly unpredictable,” he said. And that’s only natural, given the range of variables.

There were eighteen undergraduates enrolled in Teaching Children Philosophy last winter and they were assigned to seventeen different fourth-grade classrooms in the Eugene community (Lahmann and Wilson were one of only two teaching pairs). The sophistication and depth of discussion depended in large part on the skills and interests of the individual student teachers—although, as Bodin noted, “One of the harder things they have to learn is how to suppress a strong opinion if they have one about a particular topic.”

Just as important, the flow of the conversation for each week’s theme depended on the interests and level of maturity of the fourth-graders themselves.

For instance, the week before the Araboolies provided grist for the weekly philosophy dialogue, the topic was “What can money buy?” To set up the discussion, Bodin wrote a short play that introduced the idea of a person donating money to a school and having her name put on the library. What did the children think of that?

For instance, the week before the Araboolies provided grist for the weekly philosophy dialogue, the topic was “What can money buy?” To set up the discussion, Bodin wrote a short play that introduced the idea of a person donating money to a school and having her name put on the library. What did the children think of that?

In some classrooms—like Ben Dechter’s—the children spent a long time grappling with the fairness of having an individual’s name put on something that belongs to everyone. But in other classrooms, the idea of naming a building was too abstract and the conversation veered toward the idea of buying and naming pets because that was easier to comprehend.

Yet in other classrooms, children brought up provocative questions such as, What does it mean to pay to bring an adopted child into your family? Why do we need money—can’t we just barter? Why is it okay to pay for marriages in some countries?

“Fourth graders are a lot smarter than what we give them credit for,” said Darby Smith, an English major who took Bodin’s class last term and was assigned to Bertha Holt Elementary.

“They have a much higher level of thinking than what you would expect,” she said. “They are so eloquent.”

Smith was sharing her thoughts as she and her fellow Philosophy 399 students debriefed the “what can money buy?” lesson in their weekly meeting with Bodin. The students represented a mix of majors—many from education studies and philosophy, but others from an eclectic range of majors. Their common interest was a desire to get out into classrooms for firsthand teaching experience.

As they reported back on their diverse experiences with that week’s theme, it was quickly apparent that in every classroom—no matter what direction the conversation took—the children had been engaged and enthusiastic.

“I was worried I wouldn’t be able to get them talking,” said Jason Beck, a psychology major, reflecting on his early apprehensions about going out to teach in his assigned school (also Holt). “Now I can’t get them to be quiet.”

For Chase Huff, a philosophy major assigned to Adams Elementary, the questioning technique is everything. “The ‘what if?’ really gets them talking,” he said.

He’s referring to the questioning method Bodin trained the undergraduates to use: ask open-ended questions and continuously pose hypotheticals that cause the conversation to go deeper. What if the library might close if someone didn’t donate money? What if following the rules hurts someone? What if you got paid for getting good grades? This probing sets the stage for precocious reflections.

For instance, the very smallest and quietest girl in Ben Dechter’s classroom had a ready answer to the question of getting paid for grades: “You’re getting paid by getting knowledge, so you can go to college and have a good life,” she said.

For instance, the very smallest and quietest girl in Ben Dechter’s classroom had a ready answer to the question of getting paid for grades: “You’re getting paid by getting knowledge, so you can go to college and have a good life,” she said.

The boisterous conversation paused momentarily as everyone pondered this thought.

“It’s easy to underestimate how much kids can comprehend,” said Wilson, the student cofacilitator in Dechter’s class. “They blow you away and your jaw just drops.”

Channeling Energy

Dechter, a UO alum (environmental studies, ’04), has been teaching in the 4J district for eight years. This is the second year he has invited UO students into his classroom to lead weekly philosophical discussions.

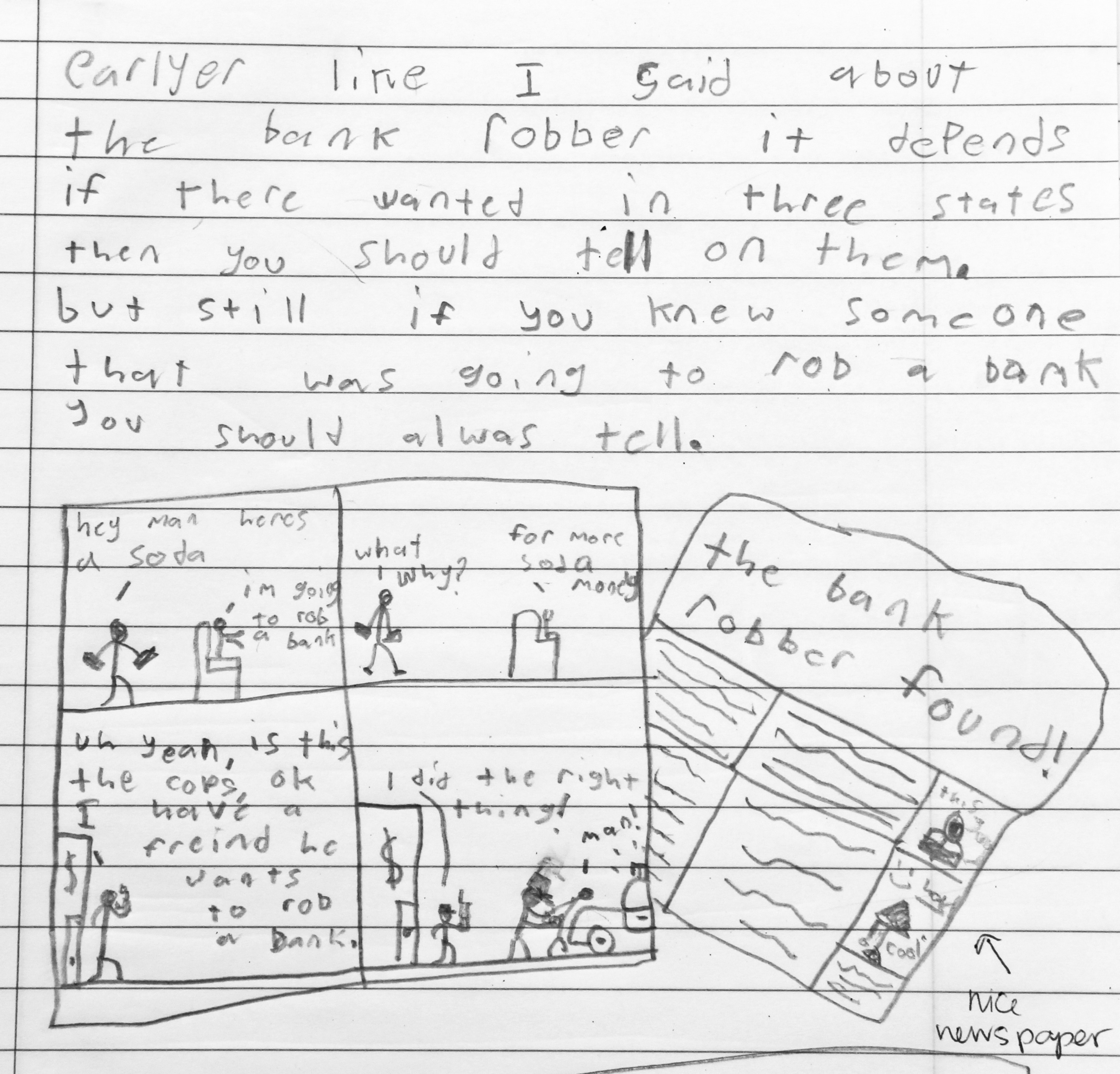

“The kids are excited about it,” he said. Even though the weekly session lasts an hour (plus fifteen minutes for journaling—see excerpted examples), “There’s never enough time for the kids to say everything they want to say. Even the quietest kids raise their hands.”

While this activity takes an hour each week out of his teaching schedule, he says it’s not extra work because he doesn’t have to prepare a lesson plan. And there’s a built-in bonus: it dovetails with core teaching objectives such as the development of language arts skills.

It’s also obvious that he gets as much enjoyment out of it as his students do. “It’s a fun role for me—to not have to be the leader,” he said. “I’m often biting my tongue, but I let the UO students lead it.”

As student teachers, Lahmann and Wilson have a tall order: they are charged with channeling the energy of an often-rambunctious class of fourth graders into a sustained discussion.

“I’m really impressed that they can keep the kids focused,” Dechter said.

A typical session involves wrangling a circle of twenty-eight squirming, eager nine- and ten-year-olds, many with their hands thrust into the air at any given moment, talking over each other and their teachers. Lahmann, Wilson and Dechter all regularly issue gentle reminders that the kids need to take it down a notch so that the person who has the floor can be heard.

A typical session involves wrangling a circle of twenty-eight squirming, eager nine- and ten-year-olds, many with their hands thrust into the air at any given moment, talking over each other and their teachers. Lahmann, Wilson and Dechter all regularly issue gentle reminders that the kids need to take it down a notch so that the person who has the floor can be heard.

The day of the Araboolies discussion was no exception. It was the second-to-last day that Lahmann and Wilson would be visiting the class, and they employed a new strategy for getting the discussion started: they asked each child to write down a question about the story and then turn it in.

Weird Is Normal

Lahmann began by asking one of the children’s questions: Why are the Araboolies so colorful? Read an extended excerpt from this dialog.

Ideas began piling on immediately.

“Because they were born on an island that made them colorful.”

“They were just born that way.”

“They probably got a genetic trait for that.”

Next question: Why doesn’t the General like fun and noise?

“He’s the boss of a part of the army, so he thinks he can command everyone and tell them whatever he wants them to do.”

“Maybe he just grew up around his parents and . . . they were too bossy to him. And so maybe he grew up around people who did that.”

“He’s probably used to being really stern because he’s the general to the army and he’s used to having people listen to him. So when people don’t listen to him, he probably gets mad.”

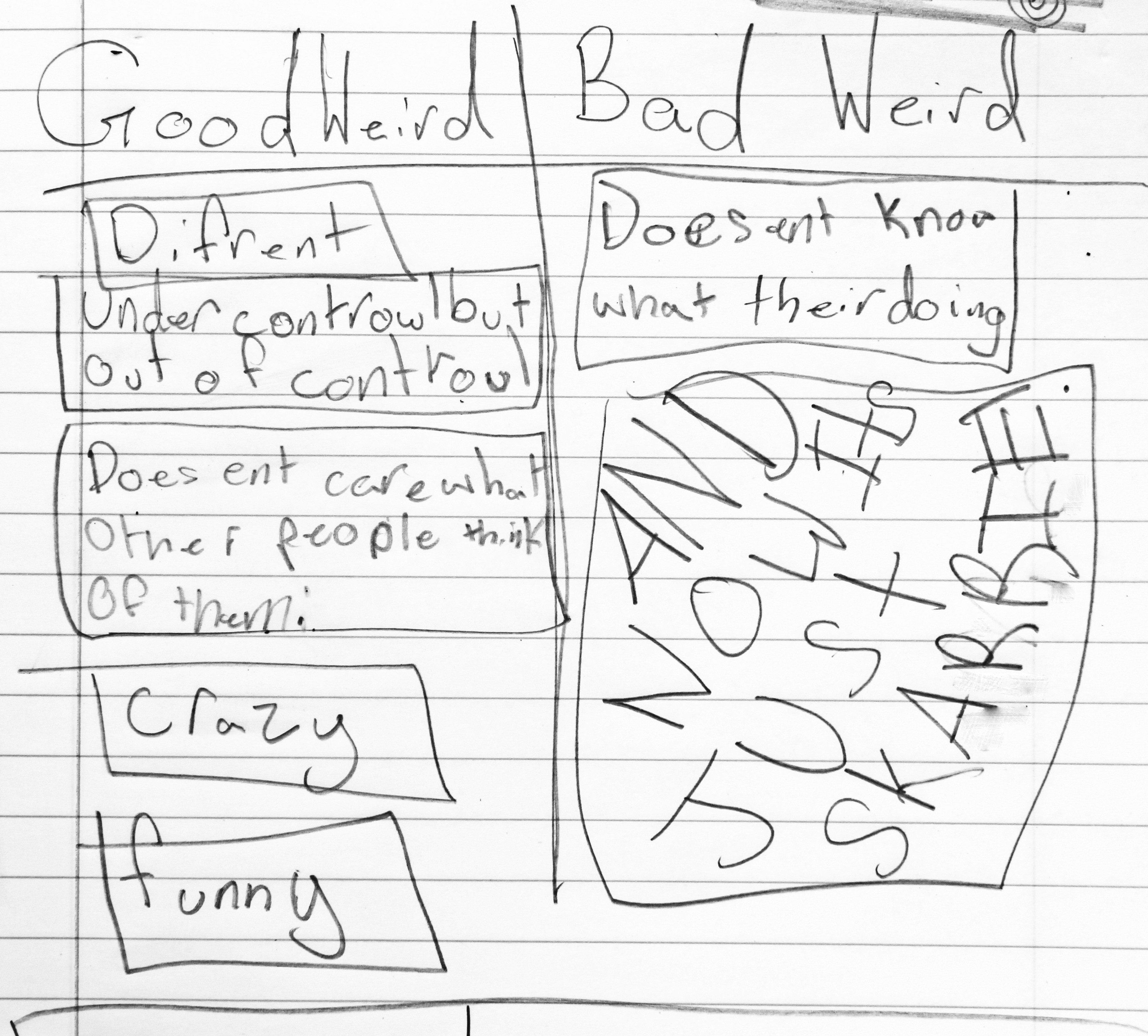

The question-and-response was nonstop and quickly led into an extended discussion about who’s weird and who’s normal. And what is normal, by the way? What is weird?

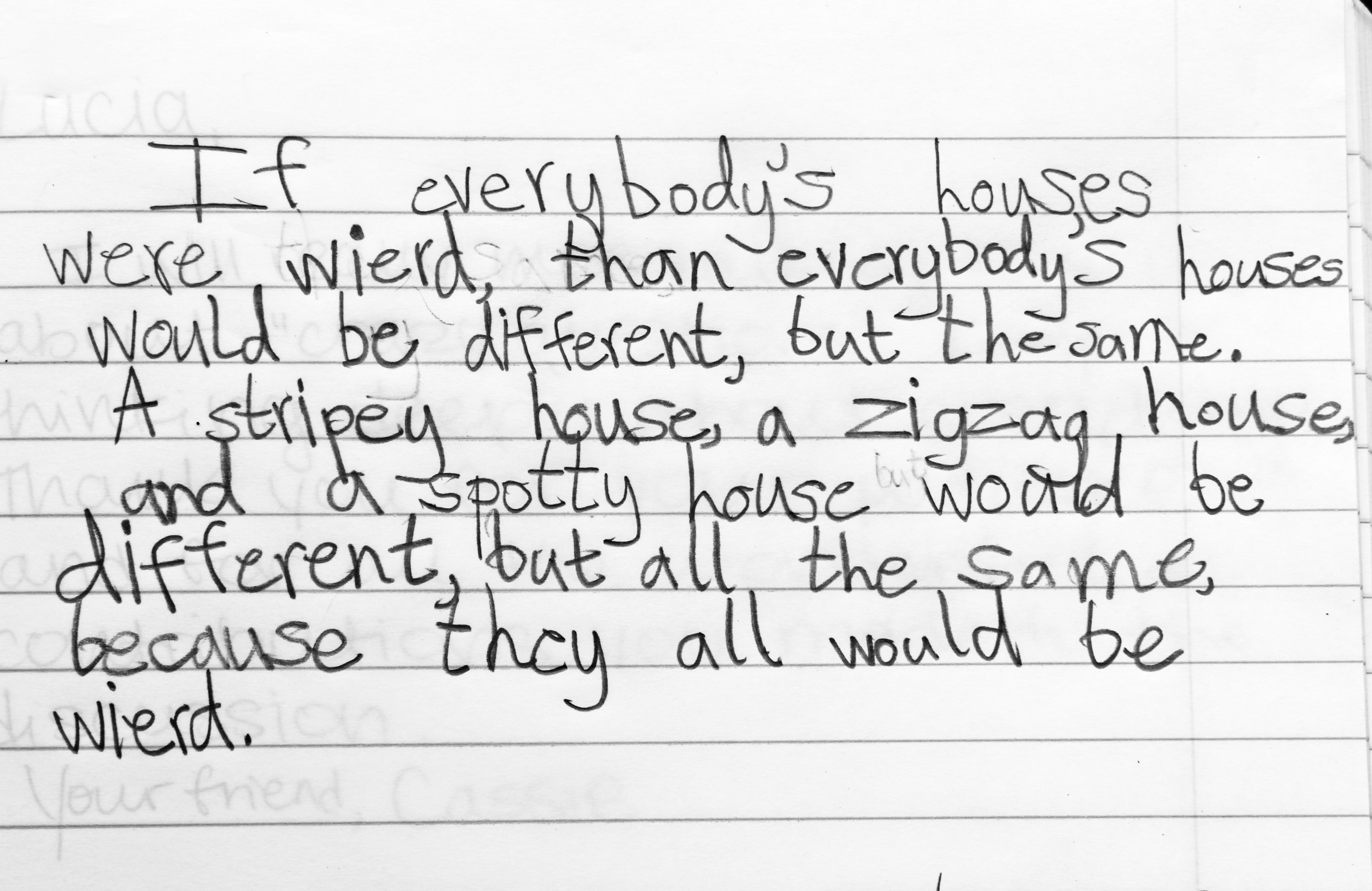

The consensus around the circle was that “it depends.” The Araboolies are weird to the General because they don’t conform to his rules. But the General is weird to the Araboolies because they don’t speak English and don’t know what he’s yelling about.

In other words—and several children said this, in one way or another—it all depends on your perspective.

A dictionary definition of “normal” was read aloud: “Normal; adjective. As it should be; healthy and natural. The normal temperature of the body is 98.6 degrees. Number two: as it is usually. Like most others. Typically.”

To which a girl responded, “That would make weird normal because lots of people are weird.”

Another point of general agreement: weird can actually be better than normal, if it means being true to yourself.

A young boy summarized, “If you’re just weird and that’s who you are, it’s a good thing because you’re being who you are.”

Not only that, but normal may actually be an unachievable abstraction. According to another boy, “Some people try to act normal, but really everybody is just weird.”

No Right Answer

This rapid-fire torrent of ideas and counterideas is facilitated by the students breaking out of the normal classroom routine. It all begins with pushing their desks into a corner and pushing their chairs into a circle, which gets them out of their usual classroom rhythm, said Dechter.

But the biggest game-changer is the open-ended questioning format. In the day-to-day reality of classroom education, there’s often an emphasis on getting the right answer. But that’s not the goal here.

The questioning approach “is not a straight-line question and answer,” said Wilson, about the methods he brought into Dechter’s class. “There might be a possible answer, but you get to see the counterargument.”

Wilson, a sophomore majoring in education, took Bodin’s class to accelerate his exposure to classroom teaching, which would normally not be available to him until later in his program.

Lahmann, an English major and creative writing minor, aspires to a career in teaching, too. In addition to taking this class, she also volunteers along with several other UO students to lead a creative writing program at the John Serbu Center, a youth detention facility in Eugene.

This extracurricular activity has provided a perfect opportunity for her to apply the teaching techniques she acquired in Philosophy 399. When it was her turn to lead the class at Serbu, her topic was fiction versus nonfiction. But rather than tell the students what might distinguish one from the other, she opened the discussion with, “What do you think the differences are?”

This was not the usual approach in the Serbu setting, which would typically involve the leader explaining, say, how to build a plot or develop a character. Lahmann’s method was to invite the students to explore their own thoughts and perspectives.

The result: “I had never seen them participating so much,” Lahmann said, adding that her fellow UO volunteers were impressed with this technique.

For their final project in Bodin’s course, Lahmann and Wilson each wrote a discussion template like the ones Bodin provided to them in preparation for each class. Lahmann wrote one about the idea of “it’s only business” versus friendship and fairness, when two friends find themselves with competing lemonade stands. Wilson wrote his about a “no girls allowed” boys club, which explored the cultural assumptions about “boy things” versus “girl things.”

“This was my favorite class ever,” said Lahmann. “It pushed me more because I pushed the students. It made me develop my critical thinking skills.”

— Lisa Raleigh

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Forward

Forward