Local Physicians Help Revive the Human Physiology Department

The prognosis looked grim for the Department of Human Physiology in the early 1990s. Legislative budget cuts forced faculty layoffs, leaving just five professors. And the student population dwindled to 20 -- the future wasn't promising..

Less than 15 years later, there are now nearly 700 undergraduates majoring in human physiology, plus 42 graduate students are conducting independent research on how the body responds to exercise, disease and trauma.

Less than 15 years later, there are now nearly 700 undergraduates majoring in human physiology, plus 42 graduate students are conducting independent research on how the body responds to exercise, disease and trauma.

The department, in other words, has made a dramatic recovery from a student interest point of view. But faculty growth has not kept pace -- with only 10 faculty members, the faculty-to-student ratio is now about 70:1.

Nevertheless, human physiology has become a program that attracts millions of dollars in grants funding cutting-edge research, and its professors are publishing in the best academic journals while undergraduates are successfully applying to the country's top medical schools.

How did this tiny department on the verge of extinction take a 180-degree turn and start attracting attention nationwide? In part -- a major part -- the revival is the direct result of dozens of professional partnerships with Eugene's medical community.

"Our local physicians have become the cornerstone of our department," said retiring Department Head Gary Klug. "We couldn't be doing what we're doing without them."

Today more than 40 physicians work with the department as instructors, research consultants, guest lecturers and student mentors. This is nothing less than phenomenal for a department with humble roots as a physical education program. Such extensive collaboration is normally the province of a university with a large medical school. But of course there’s no medical school at the UO — not yet.

From Bench to Bedside

The alliance with community physicians has done more than revitalize the human physiology department. It has also created a veritable incubator for innovative research. UO researchers and local doctors together tackle relevant questions and apply laboratory findings to real-world clinical practice much faster than the norm.

Getting research from "bench to bedside" more quickly has become a pressing goal in the Department of Human Physiology and also on a much larger scale. A 2003 study by the National Institute of Medicine found it takes an average of 17 years for research discoveries to be incorporated into routine patient care. In response, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) now bases its research funding decisions largely on whether a study's results have promising and swift clinical applications.

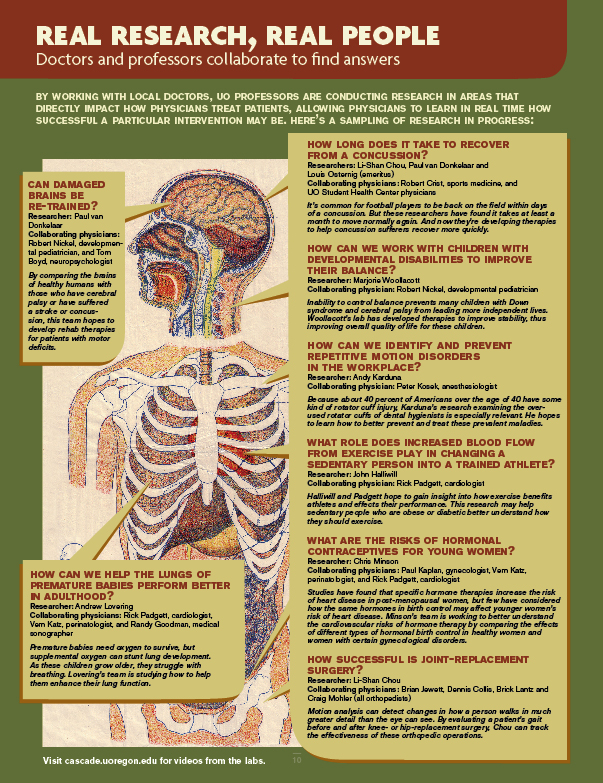

A glance at the sidebar "Real Research, Real People" (click on image below) reveals both the breadth and depth of real-world problem-solving going on in the six specialized laboratories in the human physiology department. The focus is on health problems faced by real people -- today, in their jobs, in their daily lives, across their lifespan.

Proving the NSF Wrong

Proving the NSF WrongIn the late 1990s, Klug proposed building a facility where physicians and professors could work together. He applied for a grant from the National Science Foundation, and the NSF responded by saying it was a great idea to have physicians closely connected to departmental research, but physicians would be too busy to volunteer at the university.

Klug and the rest of the department believed otherwise. They could point to examples of successful partnerships they'd initiated years before. (Nobody quite knows exactly how and when the first doctor-professor partnership began). So without the grant or the facility -- but with the help of an insider in the medical community (Klug's wife happened to be a vice president at Eugene's PeaceHealth, a regional health system based in Bellevue, Wash.) -- the department kept doing what it had been doing for years: requesting aid from area physicians one by one. Ultimately, the willingness of physicians to generously volunteer their time and expertise proved the NSF wrong.

The collaboration has been cobbled together in a way that would not necessarily suggest a trajectory for success. It works despite the fact that there's no single human physiology building or even a standardized format for the collaboration. Instead, it's often been one researcher at a time seeking out a physician partner -- or vice versa.

For instance, Eugene cardiologist Dr. Matthews Fish, of the Oregon Heart & Vascular Institute, had a pressing research question: He wanted evidence of the effectiveness of different cardiac imaging software programs, which cardiologists use to detect heart disease.

It was an important question, one that had the potential to affect how doctors everywhere analyze the heart. But Fish knew it would take hundreds of hours to analyze the data he had collected on his patients -- time he didn't have as a practicing doctor.

Most physicians have questions they're interested in investigating, but few have the time to develop and execute studies on their own. However, collaboration between Eugene-based physicians and human physiology graduate students has proven to be an ideal solution. A majority of the graduate students in the human physiology department work with physicians to some degree to help them tackle research projects.

Most physicians have questions they're interested in investigating, but few have the time to develop and execute studies on their own. However, collaboration between Eugene-based physicians and human physiology graduate students has proven to be an ideal solution. A majority of the graduate students in the human physiology department work with physicians to some degree to help them tackle research projects.

For his cardiology research project, Dr. Fish recruited graduate student Santiago Lorenzo. A native of Argentina, Lorenzo came from a long line of doctors and hoped for a career in sports medicine. At the start of his work with Fish, he was a master's student interested in getting more exposure to clinical medicine. He agreed to help Fish structure a rigorous, unbiased analysis of his data.

They created a database to process the information and standardize the results of the cardiac imaging project. With 400-500 patient records to study, it was tedious work. Lorenzo would drink maté -- a traditional, caffeinated Argentinean beverage -- to keep him going late at night as he processed piles of physicians' notes and patients' data.

Fish said, "It would have taken me years."

What they found was significant. Their analysis showed considerable inconsistencies among the different cardiac imaging software programs. These inconsistencies could lead to inaccurate diagnoses of a patient's heart condition. It was highly valuable information to the medical community and Fish and Lorenzo have since co-authored three academic/medical journal papers, with a fourth on the way.

For Lorenzo the experience was career-changing. He was inspired to continue to study the heart, now looking at how it responds to exercise. Rather than applying to medical school to be a physician, he has entered the human physiology Ph.D. program to become a researcher.

For Fish it showed the tangible benefits of partnering with the university. "Such research performed locally in our own institutions greatly enhances the quality of medical outcomes," he said.

Going to Extremes

While Dr. Fish sought out a graduate student to assist him, in many cases the researcher seeks out the physician -- and will go the distance (literally) to accommodate the relationship.

John Halliwill, associate professor of human physiology, reflected on one recent example: Halliwill is studying why excess blood flows to the muscles after a workout and how understanding this might benefit people with obesity or diabetes. To complete the study, he needed a trained medical doctor to place arterial lines (insert narrow tubing inside arteries), to measure blood flow.

Dr. Rick Padgett, a cardiologist and medical director at Oregon Heart and Vascular Institute (OHVI), has served as a co-investigator on several of Halliwill's research projects. This particular study relied heavily on Padgett's expertise. But as a medical professional with a thriving practice, Padgett didn't have the time to run over to the university every day to help. So Halliwill brought the lab to Padgett's office at OHVI.

With Halliwill's lab just down the hall, Padgett can squeeze in the lab work between his routine patient visits.

"We've managed to bring the institutions together in a grassroots partnership, which is pretty unique," Halliwill said.

Padgett agreed. "We're blazing new trails here," he said. "We're trying to create an environment that allows the collaboration to flourish."

What's the Payoff?

Over the years, the human physiology department has found that, despite busy schedules, many physicians are eager to help with very little or even no pay. Why? As Dr. Victor Lin, a Eugene rehabilitation doctor, explained, physicians enjoy challenges and intellectual stimulation.

Lin went through many years of rigorous medical training before settling into his private practice at the Rehabilitation Medicine Association. "In school, life is always changing and you're always learning something new," Lin said. "Then you hit private practice and it's 99 percent the same thing every day."

When his work started to feel like a 9-to-5 grind, Lin started looking for a new challenge. He learned of the research conducted by Associate Professor Li-Shan Chou that focused on biomechanical analysis--technology that has been used to capture and computerize Tiger Woods' golf swing. Chou uses it to assess patients who have trouble doing simple tasks like walking and going up stairs.

Lin, who loves new technology and gadgets of all sorts, was a little envious of Chou and could see how biomechanical analysis could be directly applied to his work in rehab. He called Chou and said, "My time is limited, but I would love to be involved."

At the time, Chou was beginning research to try to answer the question of why elderly people fall and he needed a physician to screen potential research subjects to determine if the person is a faller or a non-faller. Now eight years later, Lin still visits Chou's labfrequently to discuss research and watch the data collection in process.

"I like to mingle with the students and tell them how I would apply the basic science they're doing to the clinical setting," Lin said. "I used to be involved in conversations like this all the time in medical school. I missed the collegial bonding, and now I can get it from these kids."

Scrubbing In

It's not only the physicians and researchers who are enjoying the benefits of this partnership. Students may be receiving the most tangible rewards. Many have the opportunity to receive direct instruction from physicians in the classroom (see sidebar: Out of the Clinic, Into the Classroom), and some are experiencing powerful mentoring outside the classroom, too.

Each year 25 to 30 pre-med students get to shadow local physicians. "Students come into the department thinking they want to be a physical therapist or a doctor, but don't have the sense of what it's like to live the life," said Department Head Gary Klug. "We try to get them in that environment so they can see what it looks like and feels like to be a doctor."

Imagine, for instance, scrubbing in on a surgical rotation -- before even entering medical school.

Twice a week during her senior year last year, Melissa Wagasky scrubbed in for 7:30 a.m. surgery. This 22-year-old would witness three or four or sometimes even five operations a day. Though she was only an undergraduate, she was learning firsthand what it took to be a surgeon.

"It was an amazing experience," she said. "(The doctors) really just teach the entire time."

It was Dr. Robert Schauer, a breast cancer surgeon, with whom she spent the most time. During each shadowing session, Wagasky, clad in medical scrubs and a mask, would get a surgeon's eye view -- looking over Schauer's shoulder from the first incision to the final suture, while Schauer narrated his every move.

Throughout the surgeries, doctors would quiz Wagasky on anatomy, and she would point to anything unfamiliar and ask, "What's that? What does it do?" Overall she was impressed with how much her human physiology education had prepared her.

Having an extensive shadowing experience will also boost Wagasky's chances of getting into medical school. Associate Professor Paul van Donkelaar, who has been the liaison between the human physiology department and PeaceHealth, explained, "Now you need more than great grades. You need to have extra-curricular experience within the medical world."

An average of half of the UO human physiology undergraduates who apply to medical school are admitted, and nearly all shadowed physicians.

A Satellite Med School?

In looking to the future, many are eager to expand and formalize the partnership between the university and the medical community by creating a physical space to house both professors and physicians.

Department faculty dream of erecting a single building that would be a collaborative home for research with direct clinical application (otherwise known as translational research). But that's probably five to 10 years away, said van Donkelaar.

In the nearer future, the hope is for Eugene to host a satellite campus of Oregon Health and Sciences University (OHSU), home to the state's only medical school. There's been much buzz in the past four years since OHSU first proposed partnering with the UO and PeaceHealth to find a way to expand its school of medicine and thereby address Oregon's looming physician shortage.

But the chatter has dwindled some because the state legislature has thus far withheld its support. Despite this, the partners have managed to move forward anyway and have begun rotating a handful of OHSU's third- and fourth-year medical students through clinical training at Sacred Heart Medical Center (a PeaceHealth unit) in Eugene. Eventually the goal is to accommodate an additional 20 first-year medical students.

"Everyone -- UO, PeaceHealth, the clinicians -- is very keen on the medical school opening here. If the medical school becomes a reality, that will be a real catalyst to formalizing the relationship between UO and the medical community," said van Donkelaar.

Legislative support is the last missing piece. A proposal to hire faculty and develop the curriculum will go before the state legislature in February 2009.

"We just have to try to convince them that it's worth spending the money to make this happen," van Donkelaar said.

- Photos by Katie Campbell